COVID-19 has made strong supporters of vibrant urban life shudder. They are pining for the outdoors and wondering if our current dense urban form is to be blamed for what COVID-19 has unleashed. There’s speculation around what the pandemic means for cities, and especially if it should change the current path of urbanisation.

While holistic changes are welcome, many commentators have made density — a measure of population per unit area, usually square kilometre or square mile — the scapegoat.

On March 22nd, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, tweeted: “There is a density level in NYC that is destructive,” that the city must “develop an immediate plan to reduce density.”

However, evidence from around the world shows it’s not just density that is the reason for our imprisonment.

Density and Covid-19

Data shows that urban agglomerations have witnessed the maximum spread of the disease and fatalities.

| Country | Total Cases | Urban Area (most affected) | Cases in most affected area | Percentage |

| United States | 1,228,603 | New York City | 178351 | 14.51 |

| Spain | 220,325 | Madrid | 63,400 | 28.77 |

| Italy | 214,457 | Lombardy | 79,369 | 37.00 |

| United Kingdom | 202,359 | London | 24,988 | 12.34 |

| France | 174,224 | The Paris Region | 7,900 | 4.53 |

| Germany | 168,162 | Bavaria | 43,600 | 25.92 |

| Turkey | 120,204 | Istanbul | Not available | — |

| Russia | 165,929 | Moscow | 76,649 | 46.19 |

| Iran | 94,640 | Tehran | Not available | — |

| Brazil | 126,611 | Sao Paulo | 37,800 | 29.85 |

| China | 83,970 | Hubei | 68,128 | 81.13 |

This has led to arguments against densities—that an unrestrained population, a population bursting at the seams, puts severe strain on public resources and services and overwhelms public health systems.

Of course, higher population density can lead to faster transmission of the virus. In populated urban centres, with strong rates of contact and close networks, transmission rate is assumed to be higher. But suburbs, smaller towns and rural areas are not immune, either.

In fact, evidence from China, where COVID-19 is said to have originated, shows that Chinese cities with very high population densities such as Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, Tianjin, and Zhuhai have had far fewer confirmed cases per 10,000 people, than cities with population densities in the range of 5,000 to 10,000 people per square kilometre.

Researchers find that cities like Shanghai and Beijing were less affected because “the denser cities are the wealthier ones, making them more able to mobilize enough fiscal resources to cope with the coronavirus.” That, perhaps, is the clincher, though, of course, there may be other reasons too, such as early clampdown and potential censorship.

Density’s unseen advantage

In criticising density for the spread, we are forgetting that it’s because of density, where cities meet a certain threshold of population, that services to residents become efficient and viable. For instance, high density makes it possible for businesses to offer door-to-door delivery, enabling social distancing. Health infrastructure, which can facilitate high testing or treatment, too, is concentrated in dense cities.

In earlier eras, the powerful and elite city dwellers scattered to the mountains to avoid pandemics like the Cholera or Influenza. But the world is increasingly connected now, with strong transportation networks even to rural areas. Coronavirus in India, for instance, has reached Uttarakhand (55), Kashmir valley (466) and even Ladakh (20). While an infected person in mass transit can cause community spread, the one-to-one transmission can even happen at a rural grocery store or a healthcare centre.

But even if rural populations have less means to contract it, the state of healthcare in India’s towns and rural areas means they have less means to treat it. According to WHO, India’s ratio of urban density to rural density for doctors was 3.8, and 4.0 for nurses and midwives in 2016. This means that for a given population, there are 3.8 times more doctors and 4 times more nurses in urban areas than rural areas.

City-wide data

Around the world, it’s not as if cities with the highest population density such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Seoul, Bogota or Shanghai have reported the highest number of cases. As a result of high testing, early lockdown and heterogenous population (not only old), their numbers are lower than cities in Europe and North America.

In India, as of 30th April, cases in Mumbai, with a density of about 33,850 people per sq km were 7,061—the highest in India. But other dense cities don’t follow this pattern. Cities like Indore, Pune or Jaipur, that are less dense than cities like Kolkata or Bangalore, are reporting multiple cases every day. Bangalore with a high density and low cases has emerged as the biggest exception.

| City | Population Density (Per Sqkm) | Cases |

| Mumbai | 32,303 | 10,714 |

| Delhi | 20,412 | 5,532 |

| Ahmedabad | 26,000 | 4,735 |

| Chennai | 26,553 | 2,328 |

| Pune | 5,600 | 2,300 |

| Indore | 3,800 | 1,699 |

| Hyderabad | 18,480 | 1107 |

| Jaipur | 17,000 | 1099 |

| Kolkata | 24,306 | 754 |

| Agra | 1,084 | 653 |

| Bangalore | 17,386 | 157 |

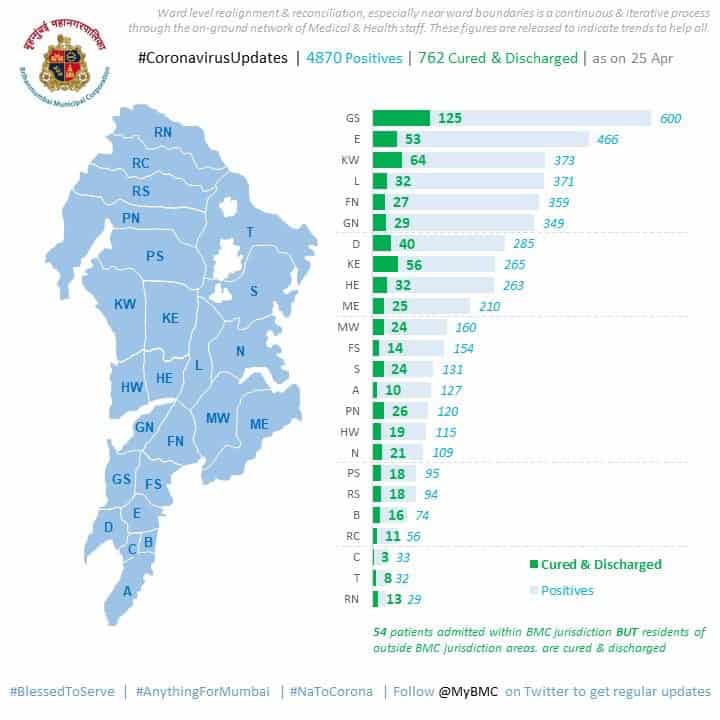

Peculiarities of Mumbai

Within Mumbai, it’s difficult to say if density is the only biggest contributing factor to COVID-19. As of 25th April (Mumbai Municipal Corporation hasn’t released latest data), Dharavi, the grand slum of Mumbai with a density of 869,565, in the G/N ward, was not the one that recorded the highest number of cases. G/N ward has 349 cases, lower than five other wards of Mumbai such as Worli-Lower Parel, Byculla, Andheri, Kurla, and Sion/Wadala.

Dharavi is Mumbai’s most popular slum. Naturally, it attracts attention and has managed to secure some relief measures. While it’s too soon to say anything, it’s possible that the government’s proactive measures, especially fever clinics, contact tracing and quarantine, have managed to reduce the number of cases here.

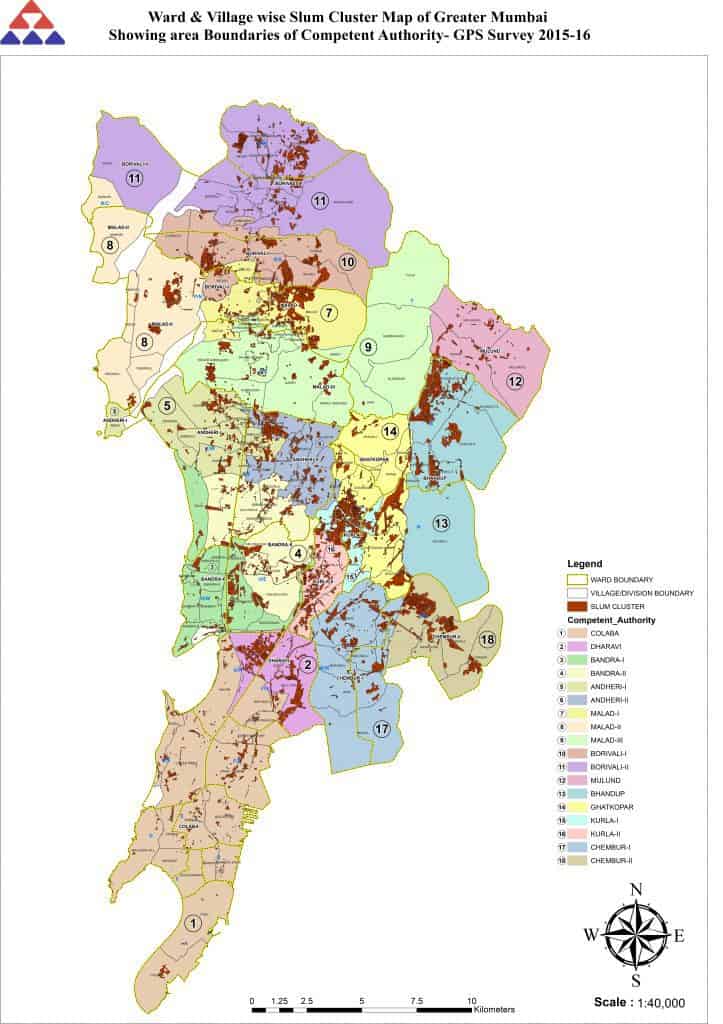

But as this map from Maharashtra’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority shows, slum clusters have proliferated in other parts of Mumbai such as Malad in the western suburbs, Kurla in the north and Govandi and Mankhurd in the north-east. Like in Dharavi, 8-10 people share one room in these slums too, with no piped water or indoor toilet, making social distancing impossible. There have been 47 cases in Versova Koliwada in the western suburbs, not just because it’s dense, but also because of the communal, interconnected nature of living here that makes social distancing impossible.

As more such evidence becomes available, it becomes clear that density in and of itself doesn’t make cities susceptible, but, as urban theorist Richard Florida has written, “the kind of density and the way it impacts daily work and living” does. This is because places can be dense but still provide places for people to isolate and be socially distant.

There’s a difference between rich dense places where people can self-isolate, work remotely, and receive home delivery, and poor dense places, which compel people to come out on the streets for basic needs such as water, access to toilets, or food.

For the rest of the world, high density is people living close together in apartment buildings with common porches and alleys; in India, it’s a life of residential overcrowding, without toilets, drainage, water, or food. More than half of Mumbai lives in slums, where social distancing is impossible, and that reflects in the city’s high numbers. This is what plays out in Mumbai, India’s prime theatre of inequality.

The idea of healthy density

Pandemics, historically, have forced humans to reimagine the spaces around them. The cholera epidemic introduced the modern urban sanitation system. The influenza epidemic led to regulations against overcrowding of slums, and towards well-ventilated houses. But a majority of people in Indian cities, especially the migrant population, are neither recognised nor given reliable basic services. It’s this lack of access to essential services such as water, sanitation, and food that makes lockdown impossible and exacerbates the challenge of responding to COVID-19 effectively.

In times like these, the call for healthy density has become louder. One paper, studying the 1918 Influenza in India, records the threshold at 450 people per sq km, above which, it finds, deaths increase. 450 people per sq km is just about India’s national population density, but the number is implausible and out-of-touch with the current urban realities of the global south.

But even for the global north, there’s an adequate response to Governor Cuomo and his argument of “destructive” density. As of April 13th, New York had 14 times more deaths than San Francisco (the second dense urban conglomeration in the US) because, experts argue, it is testing more now but also that it acted later than California.

In both the east and the west, citizens in crowded cities are suffering due to the coronavirus but the problem isn’t dense urbanism or that we lead connected social lives. Rather, the real problem is an inadequate health system, often slow government response, and our unequal and unjust economy and society.