Civil society in Bengaluru erupted spontaneously to protest the state government’s plan to set up a tree park in Turahalli Mini Forest, south of the city. A Jhatkaa.org campaign to save the forest garnered over 13,000 signatures.

Turahalli is one of the last remaining forest patches within the city. The Forest Department began work on the project without either a public consultation or placing the project details in the public domain. The project is part of Chief Minister C M Yediyurappa’s ‘Bengaluru Mission 2022’.

Following sustained protests, Forest Minister Aravind Limbavali and Minister of Co-operation and the area MLA (Yeshwantapur segment) S T Somasekhar, met campaigners at Turahalli on Wednesday, February 17. After listening to their concerns. Limbavali put the project on hold until a final decision is taken.

Protestors had won their first victory. While Limbavali takes their plea to the State Cabinet to convince the government to drop the proposal, those opposing the tree park have different ideas about how Turahalli should be conserved in future.

While all of them unanimously oppose the concept of a tree park, there is no consensus on the question of entry to the public. While one school of thought argues that there should be entry, albeit with restrictions, the other school believes that Turahalli should be locked up and left to regenerate.

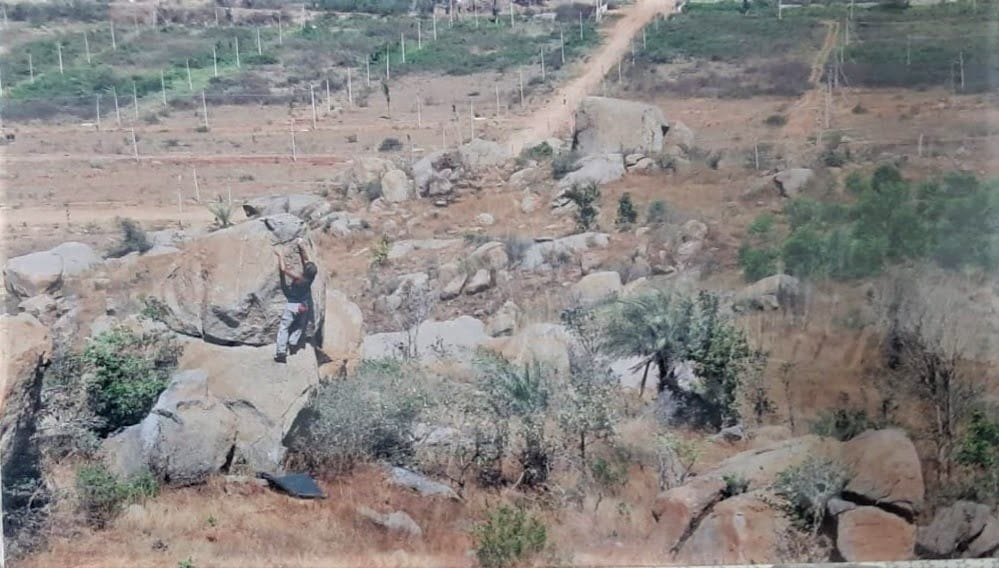

It is worth recalling that Turahalli forest had been open to the public till a few years ago, and hosted a range of activities like bird-watching and rock-climbing. Entry was cut off as recently as in 2019.

In a panel discussion organised by Citizen Matters on February 17, various stakeholders put forth their arguments on how to protect the forest. Panelists included Sanjai Mohan, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Head of Forest Force), Karnataka, Leo Saldanha of the NGO Environment Support Group, Joseph Hoover of the NGO United Conservation Movement, naturalist Deepa Mohan, and Bharat of the Save Turahalli Campaign.

Following are the three main arguments that emerged from the discussion:

1. Govt: “Tree park will enhance the forest“

PCCF Sanjai Mohan said there are misconceptions among citizens about the tree park project. He said the park would be set up only in about 50 acres of the 596-acre forest, and no trees would be cut.

“The concept of tree park came to Karnataka in 2014. There are 140 such parks across the state, and people are asking for more. Central government liked the concept so much that it has asked other States to come up with some 3-4 parks,” he said. In addition to Turahalli, such parks have been planned in two other locations in Bengaluru – Kadugodi and Bhoothanahalli – and that the city already has three tree parks.

Read more: Why has the ‘tree park’ plan in Turahalli forest irked Bengaluru?

According to him, tree parks are different from horticulture parks, and would only enhance people’s experience of the forest: “Tree parks do not have roads, manicured lawns and gardens. The walking path will be kaccha; only where there is an undulating terrain will we make it slightly walkable. And there will be a small platform where people can do yoga. We will also add more trees that will attract birds and butterflies. Forest Department knows which trees are best suited for this.”

He said the Detailed Project Report (DPR) has not been prepared yet. “This is just the first stage, we have not come to any sort of design. The project would not need much funds.”

Several audience members pointed out that a 35-acre tree park already exists adjacent to the forest. BDA had built this park, along with a sculpture park in the vicinity, in 2011; but the park is poorly developed and underutilised.

Responding to this, Sanjai Mohan said the existing tree park is on another side of the forest, away from the proposed project site. A large number of apartments are coming up around the forest, and five or 10 years from now residents there would want open spaces to walk in too; hence the new tree park is also required, he said.

The head of the forest force said wildlife would not be affected since the project was being implemented in a small area. In any case, the forest would not have leopards or elephants; it would ultimately have only birds and butterflies since it was getting surrounded by the city, he said. Many audience members said they did not expect large mammals to inhabit Turahalli, and that there were several other smaller mammals like mongoose etc., which belong to that ecosystem.

Leo Saldanha of ESG pointed out that, as per the 12th Schedule of the Constitution of India, urban forestry is a municipal function. “So constructing urban forests – which means tree parks – is really a function of the municipality and not the Forest Department. The Forest Department’s role is to safeguard forests in cooperation and collaboration with the public, both as per the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, and the Forest Rights Act, 2006.”

Turahalli has been declared a minor forest as per the Karnataka Forest Act, 1963. Diverting it for non-forest purposes would be a violation of Section 2 of the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, Leo said. This Section requires the state government to take permission from the Centre’s Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) to divert forest land. Also, as per a Supreme Court order that came later, permission should be sought from a SC-appointed committee as well.

Sanjai Mohan said the Turahalli project would not be taken forward if people did not want it, and that the department was open to suggestions from the public. Joseph Hoover of United Conservation Movement suggested that the Forest Department could instead create a tree park in Jakkur where open land is abundant.

2. A biodiversity refuge, educational space for public

Leo made a case for allowing public access to the forest, pointing out that human intervention has been critical in protecting it over time. “Turahalli is a dry deciduous forest. Not everything there is natural, groups like the Karnataka Mountaineering Association have planted trees way back in the 80s, done incredible work in shaping the type of biodiversity you now see.”

He added there have been many attempts to encroach the forest in the last 20-30 years – including by builders, forest officers and government departments – and that ESG had played a role in stopping these attempts at least thrice. Also, from 2012, ESG has worked with local villagers and Forest Department to protect Turahalli forest under the ‘Joint Forest Planning and Management Scheme’.

Read more: Turahalli: Missing the woods for the trees

But some panelists and audience members pointed out that the forest bloomed in the past 10 months when entry was completely stopped owing to COVID. This indicated the forest can regenerate by itself; human intervention would only destroy it, they argued.

Dr A Bhanu, an audience member, said, “Why are we only worried about our going and birding and bouldering? Why don’t we respect the rights of animals too? A man can go to other places, but not them.”

However, locking up the forest would also erase the natural rights of local villagers who have lived around the forest and accessed it for long, Leo said. As an example, he talked about a villager he saw in the forest recently, searching for a specific plant with medicinal properties, to treat his ailing cow.

“He knew the biodiversity of the area. Should we not learn from him? Should we not learn to appreciate the biodiversity and traditional knowledge protected under the Biodiversity Act? If anything, Turahalli should be declared as a biodiversity refuge and an educational space where people can birdwatch and enjoy the space, but certainly not to drink or expand the existing temples. I think people have that much wisdom, and local community has that much capacity for oversight,” Leo said, adding that local ward committees should also be involved in overseeing the forest’s conservation.

Deepa Mohan, an avid birder, suggested restricted access to the forest as a solution. “There could be access, say one day per week, when guards would ensure that the public would have access for a limited time, and could be counted as they come out of the forest. That would be a feasible idea now that the forest is completely fenced off and has gates,” she said.

3. Leave Turahalli alone, to regenerate

While agreeing with Leo that the forest should be protected and not be diverted for other purposes, Joseph Hoover and Bharat said entry to the forest should be completely stopped. “Bengaluru’s ecosystem has changed, lakes and forests have gone. There have to be restrictions to save the little that’s left,” Hoover said.

When asked whether this would leave sufficient open spaces for residents nearby, Hoover said there were plenty of parks already and more could be created at any location. “Do humans need everything? Can’t we do without the forest?” For example, birders can go to other locations like Lalbagh and Bannerghatta, he said.

Leo said this was a middle-class mindset. “How many people have gardens, or access to parks that give the capacity to understand the city’s wildlife? Many don’t have vehicles to travel to Ramnagaram or Savandurga to practice rock-climbing. Many who climbed the rocks in Turahalli have gone on to climb the Himalayas.”

Besides, Leo said, “The concept that forests are only for flora and fauna, minus humans, does not exist under law. There can only be restrictions on non-forest activities. If the forest is indeed locked up, somebody will challenge it in court.” Also, the policy that’s adopted for Turahalli forest would apply for all forests classified as minor or reserved forests across Karnataka, and would affect the rights of communities dependent on those forests.

“Why can’t we talk and come up with a wise-use plan for Turahalli, which can be a model for the entire country?” he asked.

Bharat said such delicate balance was a utopian concept at this stage. “Does Turahalli have the carrying capacity to include so many diversified interests? It could be villages who want to visit the temple or graze cattle, it could be birders or apartment residents. As the area gets increasingly urbanised, on what basis will you select who goes into the forest?”

Bharat said inclusivity was already non-existent when it came to natural resources – for example, Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary was closed to the public in 2016, but the elite continue to access it through resorts and homestays. “So we can only try our best to bring in parity. We can all stay away from the forest for some time. In that case, there would be no direct extractive benefits, but everyone will equally get tangential benefits.”

“Turahalli forest’s canopy is building up, it can have connectivity as far as BM Kaval, and may be to the state reserve forest on the far end. People can live healthy without even stepping into the forest because it would remain green,” he said.

The way ahead

The panel looked at the question of making the campaigns on Turahalli forest more inclusive. Bharat said the voices of apartment residents were more prominent in the current campaign, but that ‘Chiguru’ – a collective of children from the village community – was also part of it.

The panel also discussed how systemic change could be brought about to prevent projects that damage the environment. Hoover said citizens have to educate ministers and bureaucrats, who are the decision-makers, about environmental issues. Citizens are empowered with the Constitution, and have to question authorities at every point, he said.

Aleem, an audience member and part of Save Turahalli campaign, suggested forming committees to understand and analyse citizens’ varying perspectives on protecting Turahalli forest.

Watch the full panel discussion:

Also Read:

The youtube discussion spoke about seeking suggestions from stakeholders on an access proposal – where does one send such proposals? Is there an e-mail address that you can share?

I suggest – Limited number limited time access every morning. No plastic in, no wildlife out. Checks at the gate.