We have over 200 lakes in Bengaluru today. Some are amazing ecosystems, some are toxic wastelands filled with trash, and most are somewhere in the middle.

Depending on who you are and where you stay, you may or may not have a relationship with your local lake. There is a lot going on though in each of our lakes, and there is a lot more that can happen with them in the future.

Get to know about the history of Bengaluru’s lakes and how they are connected:

History of Bengaluru’s lakes

Early history

It is said that Kempegowda’s mother told him – “keregalam kattu marangalam nedu”, which means build lakes and plant trees. This was very good advice because Bengaluru was otherwise an arid region with no reliable source of water.

Most lakes in this region were constructed by farmers for agriculture. They would build bunds, short broad mud walls, across valleys, and leave an outlet for extra water to continue flowing downstream.

These lakes were primarily used for irrigation, and then, of course, as a place to play and swim and hang out. Drinking water in Bengaluru was historically taken from open wells, not lakes.

The number of lakes was insanely large. A survey conducted in 1830, for instance, records close to 20,000 water bodies in the surrounding region of Mysuru.

20th Century

In the last century, there has been a shift in our economy, with people moving from agriculture to industry and services. As farmers and farming reduced inside the city, so did our dependence on lakes.

Especially in the city centre, most lakes gave way to infrastructure. From the 1960s to the mid-2000s, lakes were filled to build the Majestic bus stand, Kanteerva Stadium, and thousands of layouts, homes, and apartments. Domlur, Koramangala, JP Nagar, and many more areas were once lakes.

Further away from the city centre, lakes were not filled so blatantly but encroached on, little by little, from all directions. The exponential increase in the value of land around the city meant farmland was suddenly worth lakhs if not crores, and so farmers sold this land to builders that made apartments, IT parks, and roads.

A lot of the housing that came up in this era, especially in the city periphery, did not have municipal sewage connections, and so wastewater from millions of homes ended up going untreated, directly to the closest lake. Lakes became swamps, and in the late 1980s and 1990s, a few lakes were filled just from the fear of dengue and malaria.

21st Century

The late 1990s to mid-2000s was arguably the worst time for lakes in Bengaluru.

We had lost hundreds of lakes permanently by now, and the few that remained were filled with sludge or construction debris. The scale of repair needed was overwhelming, and nobody knew how to fix the situation.

In 2002, a Lake Development Authority was formed by the SM Krishna government to fix lakes. However, they didn’t have any enforcement powers or an appropriate budget. The LDA was dismantled in 2014, and today is remembered best for trying to privatise the lakes of Bengaluru, a dangerous idea that was luckily and swiftly blocked with a PIL from the Environment Support Group.

Similarly, another agency, the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board, was formed in 2006, a few decades too late to the scene, and again, with inadequate budgets and powers to really make a difference.

In 2007, the BMP became the BBMP, and they were made the ‘custodians’ of lakes in Bengaluru. They were allocated some of the budget and powers necessary to actually do something and began fixing a select few lakes. Kaikrondahalli lake and Puttenahalli lake are two lakes that were successfully rejuvenated in this era. It took about five years and the significant involvement of local citizens, in both cases, before the lakes healed.

Since the 2010s, due to more awareness, better regulations, and focused budgets allocated for lakes, slowly, these water bodies are making a comeback into our consciousness as social, cultural, and ecological spaces.

Read more: Whom do you call to fix your lake?

Present day

Today, according to the BBMP Lakes Department Bengaluru has 210 lakes.

Only 167 of them are in BBMP custody, and of these only 65 have been ‘developed’.

Despite the progress, things are far from ideal. About 13 different agencies have partial control of the city’s lakes. These agencies work in silos and rarely coordinate with each other.

Further, most of these agencies do not have an appropriate budget for their functions, and so fail to do justice to their jobs.

The few success stories of lakes in Bengaluru all start with local stakeholders organising at a grassroots level to save a specific lake. But even with the support of the government, it can take years of running around in government offices and working on the ground before a lake can be saved. Here is a short clip from a documentary about the rejuvenation of Kaikondrahalli lake.

Given the amount of work that is required and the scale of the problem, the BBMP is happy to give up the responsibility of fixing and maintaining lakes, especially to corporates and private donors. While this definitely helps improve the condition of lakes in the short term, it comes with some tradeoffs.

Things today are definitely better than they were in the 1990s. Quite a few of our lakes are sewage-free, home again to birds, plants, and reptiles. There is some social and cultural activity building around lakes once again.

But many lakes are left unattended for want of budgets. The government now declares large sums of money every year for the rejuvenation of lakes, which is progress, but not enough work is seen on the ground. One of the big concerns for lake maintenance is long-term funding, especially if they are being maintained by local community groups. This becomes particularly relevant when maintenance is dependent on large infrastructures like sewage treatment plants or better stormwater drains.

Read more: Study on cascading lakes in Hebbal explains why so many of them have dried up

Geography

- Cascading lakes, stormwater drains

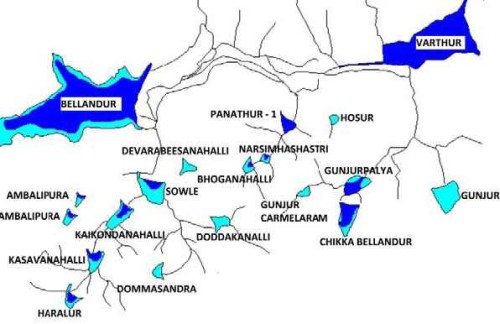

Water flows from high ground to low ground. Most of Bengaluru’s lakes are connected to each other in what is called a cascading system. Water from the 901 metre-high Ulsoor lake flows to the 874 metre-high Bellandur flows to Varthur, which is at 864 metres.

A popular way to visualise these connections is to look at lakes not individually but as a series. Depending on how you count it, we have six or seven series of lakes in our city.

Water used to flow from lake to lake in natural streams according to the slope of the land.

These streams were converted into rajakaluves, which are basically canalled with walls made of mud and stone. Today, rajakaluves are being renovated and made of concrete, and they are officially called stormwater drains. There are primary, secondary, and tertiary stormwater drains just the primary and secondary drains are estimated to have a total length of over 850 kilometres.

Our SWDs are designed for carrying rainwater only, but today they also unfortunately carry a significant amount of treated sewage. As a result, they get flooded in many places when the total volume of water exceeds their designed capacity.

SWDs are also prone to encroachment by builders. This encroachment situation is so bad that the first Google result for rajakaluve is a website that lets you check if your property was built on one.

- Valleys

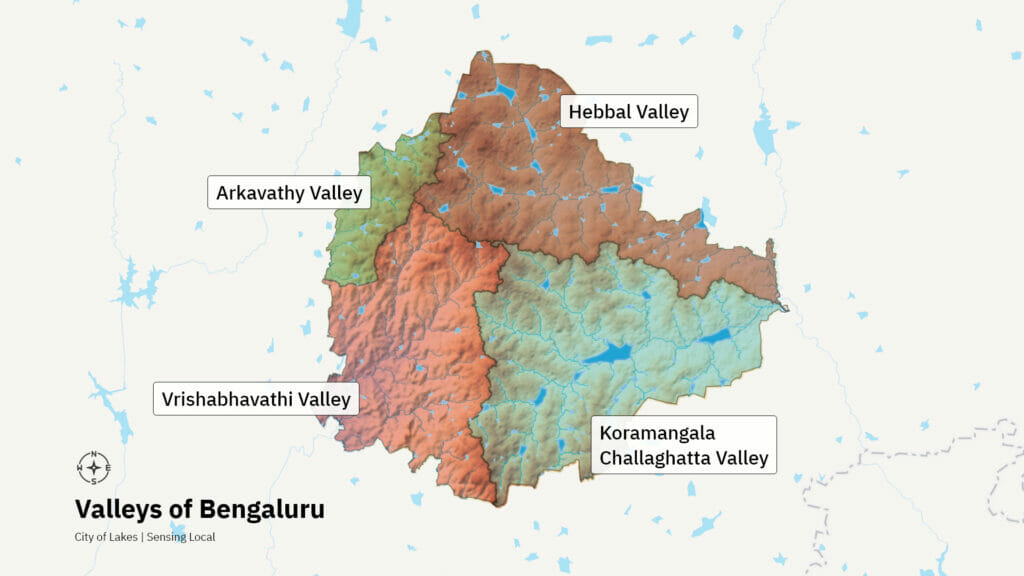

If you look at the topography of Bengaluru city, you will see there is a lighting-shaped ridge running roughly north-south, and one more running similarly in the east-west direction.

These ridges split the city into three valleys: the Hebbal Valley, the Koramangala Challaghatta valley, and the Vrishabhavathi Valley. If you consider this area, in fact, there is a fourth Arkavathy valley in the northwest. Each of these valleys is made up of smaller ridges and valleys. Water follows the natural slope of the land in search of the lowest point, which when you zoom out is the valley system of Bengaluru.

These valleys flow into two rivers, the Arkavathy and the Dakshina Pinakini. The Arkavathy is a tributary of the Cauvery. The Dakshina Pinakini empties into the Bay of Bengal.

By building haphazardly over these valleys and blocking the natural path of water, many parts of our city end up flooding every year. Major roads like ORR and Sarjapura road are good examples of this. They block the natural path of the water and so are prone to flooding, especially during high-intensity rains.

[This is the first part of the script of the YouTube channel Bengawalk’s The Secret Life of Bengaluru’s Lakes]

Also read:

- Why pre-monsoon showers lead to fish kill cases in Bengaluru’s Lakes

- A to Z guide to Bengaluru’s lakes