For more than a 100 years now (since 1911 to be specific), the world has celebrated March 8th as International Women’s Day. Every year, the day serves to highlight the strides taken by women around the world and also put together an idea of what needs to be the way forward. The idea of an equal world for men and women is still Utopian, but everyday we take some steps to achieve it, though the fight for womens’ rights is still at a very nascent stage.

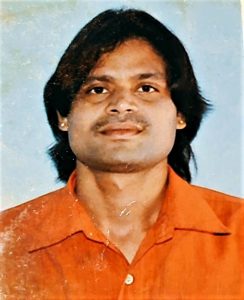

But for 37-year-old Sumangali Balakrishna, the idea of a world with equal rights is an even more distant reality than for most of us. Because she is a transgender woman. And the rules and rights aren’t the same for her. Sumangali’s life is a grim reminder of the lingering questions about who is a “true woman” in today’s world. It is a question that could challenge gender stereotypes beyond a binary narrative that is embedded in the cultural context.

A third gender isn’t an alien concept in India. If we look at the history of what we understand as Indian culture, they have always been present – in our mythology, our political systems (Nizams of Hyderabad famously had transgenders in positions as high as that of finance ministers in courts), our security systems (they guarded royal harems) etc. They were accommodated, respected and perhaps even celebrated for their difference. Western civilisation, however, was a lot less accommodating of them and history tells us how their fall from grace was accelerated after our colonisation. The British in 1871, actually termed ‘hijras’ a criminal tribe.

Cut to the modern world that we live in, there is a different set of questions that need answers about their place in society.

How do you define a woman today?

Is Sumangali a woman?

Are her rights the same that of a woman?

If she isn’t a woman, does that mean, there is a ‘right way’ to be a woman?

Has the transgender bill of 2014 failed to understand the distinctions?

Has the feminist movement been unaccommodating of those who weren’t born as a woman, but identify as one?

Do these questions that are ringing around the globe work themselves in an Indian context?

| There are no figures available in India for those who identify as trans women. They are all clubbed together as transgenders without any nuance. |

There are many questions.

Sumangali gives a simple answer “My rights cannot be the same as a woman’s. My rights need to be stronger than a woman’s because I am a transgender woman. I chose this life and my challenges are far greater. Let me give you an example. Voting is a basic right given to every citizen of India. You present yourself and get your ID. I had voted as a man when I first became eligible. When I wanted to vote as Sumangali, things got difficult. As a transgender woman, I need a gender certificate from a government doctor to get voter ID. To get that certificate, I am (was) stripped naked and physically examined to confirm that I was indeed a trans woman. Do you need to do that as a woman? If you had to do that, how would you feel? But that’s how the law mandates for my identification. Where is the dignity? That needs to change.” she asks.

But what is her take on the women who have been fighting for women’s rights – are they guilty of forgetting the rights of trans women because we forget to acknowledge them as women? Does the solidarity of sisterhood fail to attend equally to all those who identify as a woman because we don’t go through the same set of core experiences distinctive to being a woman? For example, when the demand for Women’s Reservation Bill reached a crescendo, did we forget to include trans women and if they want to be a part of that?

“We’d still get lost in the crowd, if you ask me. We will need to be accommodated separately so our voice is heard politically,” says Sumangali, “otherwise, we will end up with versions of the transgender bills that doesn’t really get our nuances.”

But didn’t the bill help the community and give them their basic rights? “It was meant to, but hasn’t really done that,” she says, adding several examples to make the point. A single woman is allowed to adopt children, trans women don’t have that right. They don’t have the legal right to get married. As trans woman, it is an uphill task to find jobs that accord you dignity, though Sumangali says she has been lucky to have found jobs like that in recent times, having worked in places like The Bohemian House (a creative co-working space) in Bengaluru.

“Most of us in the community have only two options to earn money. We either beg, or we work as sex workers. Yet, a sexual assault on me isn’t even defined by law. I had filed a complaint after being sexually assaulted once. I had identified those who had attacked me. Yet a year later, I was forced to withdraw my complaint. Women who file cases of sexual assault don’t have this challenge of having their attack undefined. So how do I compare my existence and rights viz-a-viz a biological woman? My very existence is still being defined,” she says.

A long journey

Sumangali started life as Balakrishna in Ananthpur district of Andhra Pradesh. The younger of two siblings, Sumangali says she began to identify as a girl around the time she came into fifth standard. “I always loved playing with girls, helped my mother in the kitchen, put rangoli, wore dupattas and bindis etc. I’d get bullied for it of course, but it also meant, that my family was aware that I didn’t fit into conventional role of a boy,” she says.

As a young twenty one year old, Sumangali (then Balakrishna) joined the army as a jawan. But the military training proved to be too much for her and she was discharged from training after her health failed to cope with its demands. “A lot of people ask me if I quit the army because I identified as a woman and that system doesn’t allow such leeways. Quite honestly, the training was so intense, I did not even have to time to dwell on that part of my personality. I had to leave the army because of my health. I wasn’t used to roughing it out as much,” she says with a laugh.

But despite the differences in her demeanour, Sumangali always found acceptance from her mother, even when she (as Balakrishna) wore her mother’s sarees in the privacy of their home. The only time, her mother was shocked was when Sumangali appeared before her as a transgender woman in public after her castration. “That took some time,” she laughs.

“You spoke about the challenges of being born a woman in our society. I accept them. We don’t even allow women to be born. But let me tell you about my journey to becoming a woman. There are two ways of castration for becoming a trans woman – going through a medical procedure (which costs a lot of money that most of us can’t afford) or the traditional way which we call “Dayamma Nirvana“. Our male genitals are cut without any medical assistance by an elder in the community who is trained in it. There is no anaesthesia. The pain is unbearable. If that doesn’t make you shudder, after they castrate you, they pour hot oil to stop the bleeding. We recover for months. ” she says.

| One of the leading countries in the matter of rights for trans people has been Iceland. Under the stewardship of Prime Minister Katrina Jakobsdottir, the recent Major Gender Identity Law, that allows for self identification of gender for transpeople, was passed. Before the passing of this law, they had to undergo a lengthy diagnostic process to be identified with a gender. This was especially seen as a win for trans women. |

But in a society, where men enjoy premium status and women are often relegated to the status of second class citizens, why would one even choose this for life, knowingly? “We know the pain that awaits us. But our desire to be a woman is so strong, that the pain becomes secondary. As for becoming second class citizens, our status is much lower. We aren’t even considered human.”

She suggests an experiment: “Let’s do an experiment. You, as a woman, walk ahead of me and pass a group of men. Watch out for their reaction, lust or common interest will be more common. I will then pass by them. Their reaction will more often be that of disgust and ridicule. Yet, I wouldn’t want to live any other way. We are women. But more importantly we are trans women. There is a distinction. Women’s rights for us are not the same. Yet those who fight for women’s rights can help complement our struggle too,” says Sumangali as she signs off.