At a time when the world is increasingly shifting online, there is growing potential for our relationship with the state to be mediated by technology, which can serve as a mechanism to distribute welfare, amplify citizen voices, facilitate social cohesion and support, and support direct citizen participation in state functions. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, civic technology startups are filling this role — providing information about testing centers, launching digital support groups, and much more.

As notions of citizenship are increasingly challenged, it is valuable to examine the changing nature of the citizen-state relationship, and the gaps technology can fill while still protecting human rights and individual dignity. Civic technology uses digital tools to strengthen democratic processes and enhances citizen experience through both citizen-citizen and citizen-state relations.

Currently, the behaviour of both citizens and governments is drastically impacted by changing societal norms, as governments around the world frame citizens as subjects of state control and surveillance. It is critical to rethink how the government can be held accountable through digital spaces, and the role of the citizen in doing so.

As life moves online, it is more important than ever to design inclusive and equitable technologies – especially when creating civic technology. Taiwan, for example, has a technology-enabled civic culture that has successfully demonstrated how to navigate the challenges of technology and democracy during a pandemic. Much of its success in coordinating this consent-driven and transparent process is attributed to “bottom-up information sharing, public-private partnerships, “hacktivism” (activism through the building of quick-and-dirty but effective proofs of concept for online public services), and participatory collective action”.

Most importantly, Taiwan has shown strong social inputs to coordination – social networks that support the dissemination and adoption of civic technologies throughout the country, allowing for a swift, efficient response to the pandemic.

Civic-minded organisations in India are using technology to mobilize citizens and facilitate better relationships with the state. Janaagraha, for example, has volunteers signing up for COVID-19 responders on their community policing platforms, and assists citizens with information about testing centres, helpline numbers, etc. Last week, they reported that over 35,000 individuals were reached through their platform.

Similarly, other NGOs such as Jhatkaa, Enable Vaani, and change.org, have also developed tech-enabled solutions that allow the citizen to identify demand and communicate information to local governing bodies, moving away from top-down civic technologies and driving examples of citizen-led platforms.

However, we need to be able to take citizens further, by building platforms and technology from the ground-up and designing them with citizens at the centre. Especially in the time of a crisis, there is a need for civic technology platforms that facilitate self-government and mobilization efforts more strongly.

Reaching every citizen

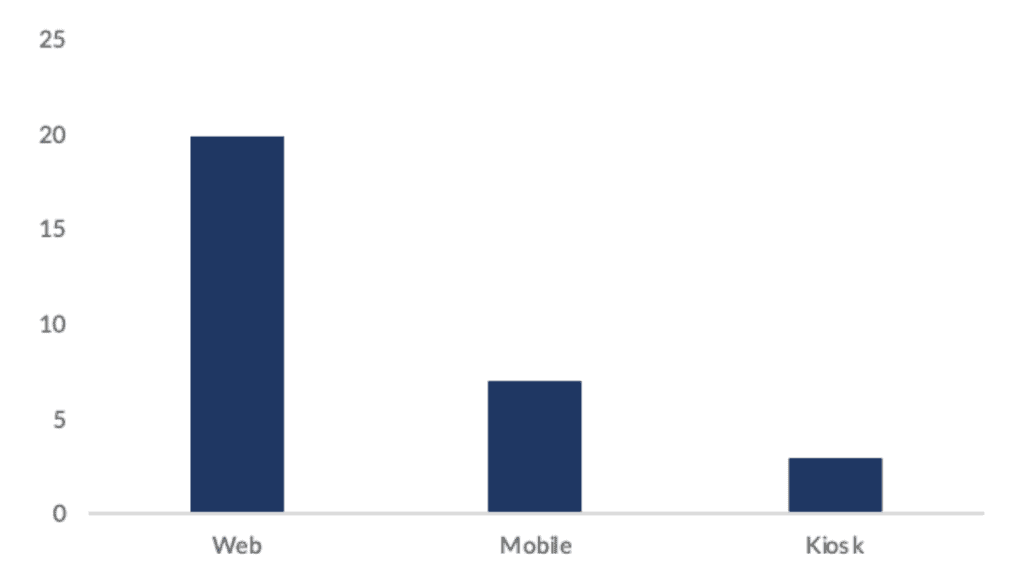

Local data and knowledge is extremely critical to shaping responses on the ground and finding relevant solutions for communities that may lack access to technology. As shown in the graph below, our research highlighted that civic technologies in India primarily rely on web and mobile interfaces. This means that questions of access for those without web and mobile connections must be considered especially in reaching the last mile citizen – and requires a greater investment in offline architectures.

By expanding citizen touch points and increasing the number of offline support mechanisms to facilitate the spread of civic technologies, a larger number of citizens can be empowered to hold state institutions accountable.

Haqdarshak, for example, is a Pune-based civic technology organization that connects citizens with their eligible welfare schemes. Once a citizen is matched with a scheme, Haqdarshaks come to the citizen’s home to help them manually apply for these schemes. In more rural areas, citizens are directed to their nearest service center. This type of human-mediated support system is critical for the last-mile access of technology and especially important for ensuring a voice for the urban poor, non-tech savvy citizenry, low-income groups etc.

In addition, the role of the citizen needs to be strengthened. Our research shows that civic technology that supports direct citizen participation in democratic processes and strengthens the citizen voice is strongly lacking, even though bottom-up technology solutions are the need of the hour.

The time is ripe

In the present reality, given social distancing and the need to move government engagement online, there is a need to facilitate deeper and more meaningful engagement with the state through effective technology solutions.

Civic technology can be used to create tools to ease citizen access to welfare and grievance redressal, and citizens can also use these platforms to keep institutions accountable for issues like spread of misinformation and lack of adequate information.

COVID-19 presents us with an opportunity to build online spaces now and for the future, that can do better in linking the citizen and the government. The design of civic technologies requires a deep understanding of the citizen experience – by understanding the needs and rights of citizens, we can further enhance their ability to support and contribute to their communities and maximize their capacities in responding to a pandemic.