The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) has forecast 2021 to be the hottest summer season in recent years in many parts of the country. On March 24th, Delhi recorded the hottest day of the month in 76 years. In fact, 2019 was the seventh warmest year in the history of humankind after 1901. Summers in India are becoming increasingly unbearable and cities are finding it hard to cope with heat wave related incidents. A study by scientists at IIT Gandhinagar has forecast an eight fold rise in heat wave related incidents in the country if the global community fails to check the rise in temperature.

The country is at present also grappling with the severity of the second wave of COVID-19, which has overwhelmed healthcare systems. And with the onset of summer in India, cities now face the dual challenge of managing the pandemic and heat impacts, which can further aggravate the ongoing health crisis.

| Year | Number of states impacted by heatwave |

| 2015 | 9 |

| 2016 | 13 |

| 2017 | 17 |

| 2018 | 19 |

(Source: NDMA)

Increasing deforestation and rampant, unplanned construction are contributing to the extreme rise in temperatures, even during night times. A study by IIT Kharagpur across 44 cities highlighted that there is an increasing trend in night time urban heat island intensity. The study blamed increased human activities for the rise in temperature. As more and more people move to cities to make a living, issues like land use change, infrastructure development, increased energy consumption are resulting in higher temperatures during summers in the country.

Read more: Varanasi’s horrible air quality typical of issues faced by cities of Indo-Gangetic plain

“The immediate priorities have shifted with COVID but there is increasing recognition of the dangers of the climate crisis among policy makers,” says Dr. Gulrez Azhar, Adjunct Policy Researcher at Rand Corporation. Dr Azhar has worked on issues of heat adaptation for over a decade.“City health plans have become a part of adaptation planning in several Indian cities,” adds Dr Azhar. “Hopefully, with the pandemic coming under control, heat will get its due attention.”

Heat waves are extremely harmful to public health. As per National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), heat waves have emerged as one of the most hazardous weather events in the country. In 2015, more than 2000 people died due to heat related incidents. 94 deaths were reported in 2019. However, experts believe that deaths due to heat waves remain highly underreported.

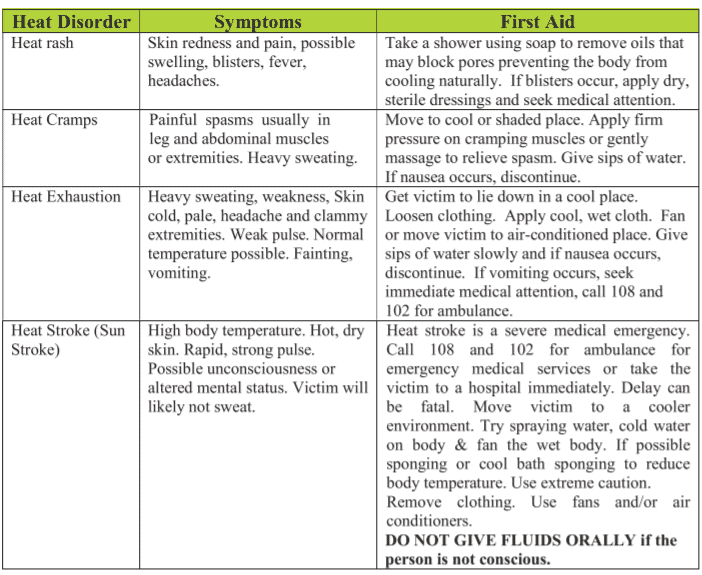

Headache, dizziness, dry skin, vomiting are some of the common symptoms of heat related illness reported during summer in India.

Apart from directly causing sunstrokes, researchers see heat as the catalyst which worsens existing issues. Studies show its impact on productivity loss, mental health, mass migration, conflicts, food shortages, economic development etc. With an already underfunded and over stressed health system, heat will no doubt exert additional pressure on healthcare systems”.

– Dr. Gulrez Azhar

The Lancet Countdown 2020 report on health and climate change notes that heat related incidents are becoming more and more frequent, creating a large impact on public health. The report highlights that almost three lakh people (older than 65 years) accounted for heat-related mortality between 2000 to 2018, of which maximum were in Japan, India and Europe.

(Annual heat-related mortality in the the 65+ population averaged from 2014 to 2018. Pic: The Lancet Countdown 2020 report on health and climate change)

Local conditions

The report also points out that rise in heat stress and related events is increasing transmission rates of infectious diseases (dengue and malaria for instance). The hot conditions are also degenerating wildlife, creating risk of new zoonotic diseases.

Air conditioning continues to be the dominant way of cooling, yet it remains the largest contributor to CO2 emissions. The report suggests sustainable cooling methods should be practised. Urban greenery is also a promising way to address the problem of heat stress in urban areas.

Read more: Can Bhubaneswar’s smart city infrastructure withstand summer heat stress?

“While disaster agencies have recognised heat as one of the disasters given its scope, scale and future projections, far more needs to be done in this area,” says Dr Azhar. In the context of Indian cities, Dr Azhar says the need is to design tailored solutions based on local needs and resource availability. As most of the available research on the subject of heat mitigation is western, “without local research we will simply be modifying western solutions to suit local contexts,” he says. “Air conditioning, for instance, remains an easy solution in the west, given it’s low cost and universal availability, but may not be practical in India”.

NDMA guidelines

NDMA in 2019 issued detailed guidelines for the states and cities to prepare an action plan on heat wave and its mitigation. The plan focussed on several aspects of heat wave like early warning and communication, role and responsibilities of agencies, risk assessment, data analysis etc. However, the plan has not been upgraded keeping in mind the ongoing pandemic situation.

The guidelines suggested the following steps:

1. Identifying the relevant stakeholders at the state, district and municipal level and ensuring their participation.

2. States to appoint a nodal agency and nodal officers at the state or district level to oversee implementation of the plan during summer in India and building capacities among key stakeholders.

3. States are required to conduct area-wise vulnerability assessment during the summer in India and establish a system of alerts for a minimum threshold. They are to coordinate with IMD for this.

4. States are required to set up a mechanism for the summer season forecasts from March to June and an early warning system for daily alerts. The guidelines also suggest colour coding of warning signals.

5. States should form a team comprising key officials who are ready with an emergency response plan, detailing clear roles and responsibilities.

6. States to carry out intensive information, awareness and communication activities (IEC) for disseminating messages in the community.

7. Every heat season, states and agencies have to assess the efficacy of the plan and update it as per needs and impact. The revised plan shall be put out for notice.

8. Lastly, the state government shall brainstorm on developing long term mitigation strategies for extreme heat, like increasing green cover or implementing cool roofs etc.

The way forward

The guidelines also share in depth roles and responsibilities of public health agencies. For example, the directors of Community Health Centres or Primary Health Centres in states/districts are required to have a standard treatment protocol for heat stroke related cases, an operational plan for issuing advisories, hospital preparedness, community surveillance and weekly monitoring. The responsible agency is also required to maintain Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) for cases outside the hospital. Ensuring adequate arrangement of beds, staff and medicines also form an important mandate for the concerned authority as per the guidelines.

Also read: Battling the climate crisis in Tier 2 cities: What can we all do?

The guidelines talk about robust data management. As per NDMA, district and state level disaster management authorities shall be liable for recording the illness and casualty related data on the basis of age, sex, occupation, economic status etc. NDMA guidelines unequivocally say that data is extremely necessary for having a “sound and evidence based policy”.

The guidelines further advocate long term mitigation methods like implementing cool roofs, increasing green cover etc. It puts focus on marginalized communities which rank highest on the vulnerability index. The plan recognizes the living conditions in slums or low income housing areas where issues such as improper ventilation, heat trapping roofs, lack of shade etc. are common.

Also, the inability of such communities to access public health systems makes the situation even more challenging, notes the plan. Therefore, creating an equitable public health system is one of the key recommendations of the NDMA guidelines on heat waves.

States like Andhra, Telangana and Gujarat have updated and made new plans based on the 2019 guidelines. While states like Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh continue to follow the 2018 plan.

Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Greater Hyderabad remain amongst the very few cities that have created their own and local specific heat plans.

“It is imperative for policymakers to create a uniform action plan to combat heat stress and wave in the most affected urban areas”, says Sachdeva. “Early warning systems can play a crucial role. With the pandemic raging, it becomes mandatory that such plans take into account COVID related scenarios too”.

COVID-19 and heat

The Lancet study says that extreme heat during the summer in India has made people with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases more vulnerable. This overlaps with the ongoing COVID-19 wave, to which people with respiratory or heart related disorders are at greater risk.

As per a study published in Geo Health Journal, extreme climate change has an important role to play in the COVID-19 outbreak in India. The study found that almost 72% of the COVID-19 cases clustered in regions that have extreme heat temperatures. The study also notes that there is high linkage between the daily COVID-19 cases and local temperature. Areas having a temperature in the range of 27 to 32 degrees and with 27% to 45% humidity witnessed a cluster of cases.

Informal housing or smaller urban agglomerations continue to remain at the forefront of extreme heat and COVID-19, says the study. The poorly ventilated houses, use of cheap materials for roofs (like tarpaulins) act as heat trapping elements, increasing the risk of transmission of COVID-19. Cooling applications like fans or air coolers should be deployed to mitigate heat related risks in these zones.

Places with poor ventilation and high humidity have also been classified as high risk places by public health experts – like public toilets.

Hot weather has a high potential to put vulnerable groups at greater risk during these pandemic times. It can also exacerbate the physiological conditions and social susceptibility amongst these groups. The Global Heat Health Network says that COVID-19 has amplified the health risks of hot weather. With cities across India reeling under the second wave of infection, increasing patient loads will raise occupational health risk for frontline workers.

“Heat is seen as a great inequality issue of our times,” says Dr Azhar. “Vulnerable groups disproportionately see its worst impacts. Targeted and amplified public messaging on heat protection can be life saving. Targeted temperature displays, heat alerts, health facility strengthening, staff training etc. can play vital role in mitigating the risks for vulnerable groups.”

Groups vulnerable to hot weather as per the Global Heat Health Network

1. Senior citizens (65 plus and especially people older than 85 years)

2. People with comorbidities like cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, kidney disease, diabetes/obesity, mental health issues (psychiatric disorders, depression)

3. Essential workers who work outdoors during the hottest times of the day

4. Health workers and auxiliaries wearing personal protective equipment

5. Pregnant women

6. People who have, or are recovering from, COVID-19

7. People in prison, or residential institutions especially if cooling measures are not in place

8. People living in low income or inadequate housing, including informal settlements

9. People living in nursing homes or long-term care facilities, especially without adequate cooling and ventilation