L Kumar, a resident of Vadapalani, was on his way to T Nagar on his bike. It was one of those rare days when the weather in Chennai was pleasant and the road was free of traffic. All was well until Kumar encountered a herd of stray cattle which barged into the middle of the road abruptly. In an attempt to avoid colliding with the herd, he hit the brakes hard. He slipped from his bike and hit the ground. The accident left Kumar with a dislocated shoulder, a fractured elbow and injuries to both his legs. The bike was damaged beyond repair.

“It took me more than eight months to recover,” says Kumar.

This is not an isolated incident. Any regular commuter on Chennai’s roads is likely to have encountered such herds of cattle. While some would have had a narrow escape, others may not have been as lucky. Not only are the cattle roaming the city’s streets a danger to commuters and even pedestrians, their loitering also puts the animals at risk of harm.

While punitive measures are in place by the civic body to curb the issues caused by stray cattle in Chennai, a conversation with the cattle owners and the residents also reveals the need to look beyond the imposition of fines to solve the problem.

Commuters struggle with stray cattle in Chennai

While Kumar’s experience with the stray cattle was on the arterial road in Chennai, J Latha has had many close calls due to stray cattle in the narrow streets of Janakiraman Colony in Koyambedu.

“I have to travel to Mount Road from Koyambedu every day. The cows and bulls would be feeding from the garbage bins placed at the end of streets every time I pass through the area. They block the roads and cause traffic congestion, particularly during the peak hours when the school and college buses pass through the same roads,” she says.

Sudha, another resident of Velachery, points out that when cattle are left to stray on the streets, the frequency of accidents increases.

“The roads are full of potholes. Even after a short spell of rain, the roads become inundated, leaving no space for pedestrians or commuters to pass by. When the cattle are left straying on roads during such time, it becomes very dangerous for both the commuters and the residents,” she says. “In most cases, the cattle owners look after the cows vigilantly as they need them for the milk but would let the bulls stray on the roads which cause much trouble to the residents.”

A young mother from Madipakkam, G Madhu, points out that the residents depend on the cattle owners for cow’s milk and would not want them removed altogether from the area.

“If the cattle owners are asked to pay hefty fines, they would end up increasing the price of milk. Those houses that have children at home depend on these cattle owners for the milk. We also understand that the cows need open space for grazing,” she says, adding that the government should come up with a solution that is practical and considers all stakeholders involved.

Read more: Will stray cattle continue to hold up traffic in ‘Smart’ Chennai?

Cattle owners of Chennai take a stand

Saravanan’s family moved to Chennai two decades ago. For over 15 years he has been making a living by selling milk in the neighbourhood. He supports his family of four with the income he gets from his five cows.

“We live in a rental house. We tie the cows in the nearby temple land. Of the five cows, only two give milk now. We are selling the milk for Rs 50 per litre to 30 houses each day. I earn Rs 1,000 per day. The expenses for the cattle is around Rs 400 per day and we use the remaining Rs 600 to pay the rent, school fees, food, travel and medical expenses,” he says.

Saravanan, like many other cattle owners, is not opposed to any action taken by the government against the cattle owners who let their cows and bulls stray on the main roads that cause accidents. However, he says that the civic body workers were even impounding the cattle that were found in the bylanes, on the side of the streets, without causing any inconvenience to anyone.

“We understand if they catch the cows, bulls and buffaloes from the main roads but their vehicles stop at open grounds and interior streets, where the animals are grazing without any disturbance to the public. I had to pay Rs 6,000 once to take back three of my cows which were impounded in such a manner,” says Saravanan.

He also adds that cows were injured while being impounded. When such a scenario arises, the owners have to bear the brunt of medical expenses for the injured cattle. On the issue of bulls being left to stray often, Saravanan says that a majority of cattle owners these days give away the bulls to farmers or sell them to slaughterhouses.

“The primary reason we let the cattle loose is for them to graze in open space. This improves reproductive capacity, as the livestock socialises naturally, with less competition; it also reduces the risk of infectious diseases as they are dispersed, provides exercise and reduces foot problems. It is an important part of the ecosystem. However, due to urbanisation, open spaces have reduced, resulting in livestock roaming on the roads and feeding on garbage,” says S Mahesan, a cattle owner from Arumbakkam. “Framing policies that prohibit cattle in city limits are not feasible.”

Ranjani R, a single mother in Saidapet, has three children. She has four cows that serve as her only source of income. “After my husband died five years ago, all I have been able to do is make a living with these cows. In the past two months, my cows have been impounded at least twice and I had to pay Rs 4,000 as a fine to bring back the cows. The residents need milk, but the government will not give space for the cows to graze. How is impounding a solution?” she asks.

Read more: Fresh milk suppliers in Chennai struggle in the face of lockdown curbs and fodder scarcity

Holistic measures needed to tackle stray cattle in Chennai

The Veterinary Division of the Greater Chennai Corporation’s Public Health Department has increased the fine amount on cattle owners to Rs 2,000 per animal for the first two days with an additional charge of Rs 200 per day from the third day. The GCC has been impounding stray cattle and imposing fines ranging from Rs 1,000 to Rs 10,000 over the years.

According to Dr J Kamal Hussain, City Veterinary Officer of the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) there are 15 impounding vehicles, one per zone, and five persons have been deployed for each vehicle to impound stray cattle.

“The team first attends to the spots specified in the complaints by the public and also inspects other areas in the locality where stray cattle could cause traffic disruption. The cattle are then brought to the corporation sheds in Pudupet and Perambur. Once the owners pay the fine, they are returned to the owners with a warning and advisory note,” he says.

The Sanitary Inspectors and Sanitary Officers look after the impounding work which is monitored by Veterinary Inspectors and Zonal Health Officers at the Zonal level.

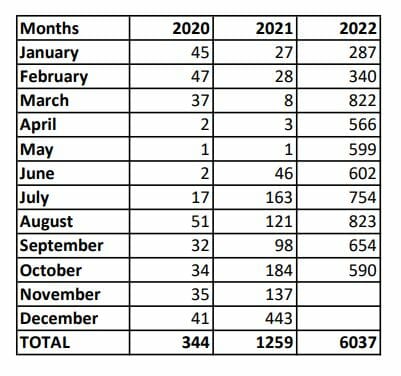

Increasing fines has considerably reduced the stray cattle menace in Chennai, says Dr Kamal, pointing out that since the civic body intensified the impounding drive, the owners have started tying the cattle with ropes and taking them out to graze instead of letting them loose on the roads.

While the GCC’s role stops at curbing stray cattle menace on Chennai’s streets, the plea for pasture lands should be made to the Animal Husbandry department. The officials concerned say that it is a policy decision that requires better interdepartmental coordination.

Pavithra Sriram, an urban planner based in Chennai, says, “When seen abstractly, the steps taken so far seem like a traffic calming measure. However, akin to the issues of street vending on which the local economy relies, there is a community that depends on cow’s milk which brings the demand for cattle in the locality. Why else would a cow be reared in an area, if there is no need for it?”

“It is irresponsible to let the cattle stray on the roads. At the same time, not giving them a solution but just penalising the owners does not seem to be an ideal thing to do either. Maybe, finding a way to regularise their business would be a potential solution to the issue,” she says. She suggests that finding places like open grounds where the cattle could be stationed, whether government or private property, would help all the stakeholders.

The issues pertaining to livelihoods of cattle owners, the micro economy revolving around urban cattle and the very need for inclusive urban spaces for animals has to be addressed to find a permanent solution to this problem. Until then, impounding the animals and imposing fines, while a deterrent, would only add to the woes and discontent of the cattle owners.