Flanked by the Outer Ring Road, where unceasing traffic spews noxious fumes, and a concreted canal where heaps of plastic float amid sewage, the Hennur Lake Biodiversity Park is an incongruous speck of green in a wide swath of concrete. And for a few slender loris individuals, it is an unlikely home.

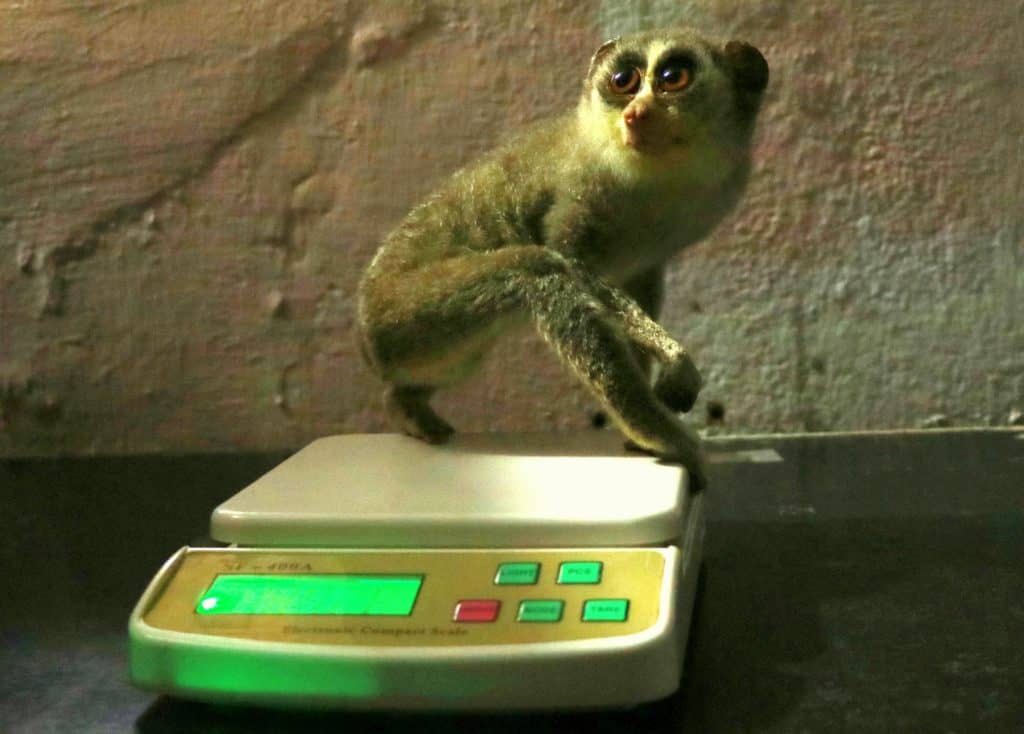

As implausible as it may seem, gray slender lorises (Loris lydekkerianus) have clung to life while the city’s concrete-scape has cornered them into this 34-acre park. At least 4-5 individuals of the beady-eyed, small, elusive primate species has been spotted in the canopies of the park. Surveys conducted between 2015 and 2017 had spotted two infants, signifying a breeding population.

“We can’t say for sure how they came about here,” said Vidhisha Kulkarni, from the Urban Slender Loris Project (USLP), a citizen science project that surveyed and studied the primates in Bengaluru between 2014 and 2017. “Perhaps, they ended up being isolated here due to the loss of greenery around them. Or, perhaps, they had been left here by animal rescuers in the city.”

As recent as 20 years ago, the park was connected through canopies to the wetlands of the Hebbal-Nagawara valley. The shrubs and trees that lined the Rajakaluves (stormwater drains) provided a corridor for lorises to travel to the IISc (Indian Institute of Science) campus, about 11 km in the west, or to the verdant green campus of the University of Agricultural Sciences’ GKVK campus 13 km to the north.

First came the broad Outer Ring Road which sliced through the canopy. Then, the wetlands of the valley itself became residential areas and towering IT complexes. Only the woodlands in Hennur provided a sanctuary.

“But, as we surveyed the place, we could see the threats playing out in real-time. Trees were being cut and piles of garbage were being burnt around the park. This is such a small, isolated patch of land – we don’t know what will happen to this population in a few years,” said Vidhisha.

Thinning canopies, vanishing lorises

The grey slender loris, which spends most of its time in canopies, has a range from southern Andhra till the southern tip of India and into large parts of Sri Lanka. Bengaluru comes in the northern end of the range, and before it became the country’s third most populous city, it was also home to a significant number of lorises.

This is reflected in the interviews of old-time residents, conducted by USLP. Lorises were sighted all across Bengaluru, even in the congested heart of the city, till a few decades ago. The timeline varies from area to area.

Lorises disappeared from the centre of the city about four decades ago, while they have been spotted in other areas as recently as 10 or 20 years ago. This information is from interviews, and need to be taken with a pinch of salt. “Lorises are elusive creatures and people’s memories can be dodgy with dates,” said Vidhisha.

And then, Bengaluru exploded, leaving slender lorises to scamper towards the remaining green spaces or to perish.

Researchers from IISc tabulate, through satellite imagery, that between 1973 and 2017, Bengaluru’s urban built-up area rose by 1028%, while the area under vegetation declined by 88%.

What were continuous patches of woodlands, scrub forests or trees in valleys, became isolated patches of green. This is most stark in southern Bengaluru’s Turahalli forest, which has been split into two. This can have catastrophic effects on populations of lorises, who, unlike monkeys, neither jump between branches nor are seen descending on the ground to cross wide open spaces.

A connected canopy is key to their survival, and this is seen in ULSP surveys conducted in 2015 on the current distributions of the nocturnal primate. The surveys showed established populations in eight patches – a majority of them in north Bengaluru, which is home to remnants of a contiguous canopy cover spanning research institutes and public sector enterprises.

North Bengaluru has not been spared from Bengaluru’s urbanisation, but it is home to some of the last remaining large contiguous patches of greenery. The best among these as a loris habitat is the leafy campuses of IISc that connects with Central Power Research Institute, University of Agricultural Sciences, Raman Research Institute, the upmarket Sadashivanagar residential area and Sankey Tank. This spans an area of 6.58 sq km, with canopies enabling movement of slender lorises.

“Our campus has four families of slender loris as we have appropriate and secured habitat. The animal also gets adequate food here,” said T V Ramachandra, from the Centre for Ecological Sciences at IISc.

Apart from the canopy cover which has defined the campus since it was established more than a century ago, IISc has also created a mini-forest which houses over 49 indigenous tree species of the Western Ghats. The 1.74 -hectare forest, planted a little more than 25 years ago, has provided a sanctuary for slender loris and even the jungle cat.

ULSP’s surveys within the campus have indicated that lorises tend to favour native trees which attract more insect populations than non-native species such as acacia, copper pod or gulmohar. There is some sort of adaptation of lorises to urban life, with ULSP researchers and volunteers observing their use of lampposts where the lights attract a veritable buffet of insects.

However, even the IISc campus has seen its fair change of changes: older, smaller labs have given way to multi-storied blocks. A clump of trees where lorises were spotted in the 2015 survey has been replaced by a concrete building. Meanwhile, canopies across the main roads that connect IISc to neighbouring campuses are thinning out.

“Creation of mini-forests in each ward [of the city] would act as islands of biodiversity. Apart from creating mini forests, we need to have canopy connectivity. Otherwise, with the chances of inbreeding, the population becomes non-viable,” said Ramachandra, who emphasizes the need to revive the traditions of planting species such as figs, mango, tamarind, etc., along roads which acted as canopy bridges earlier.

Studying lorises in a stressed habitat

The shy slender loris, which scuttles away in the presence of humans, occupies a strange space in local beliefs. Kaadu Papa (literally translated to “forest baby” in Kannada) is believed to have medicinal properties, while some others believe these stealthy creatures to possess black magic. In some extreme beliefs, blinding the bulbous eyes of the loris is believed to cure cataract.

However, contrary to popular perception, slender lorises in Bengaluru don’t face the threat of poaching or capture for black magic practices. Anthropogenic disturbance and landscape change are the big killers.

People for Animals (PfA) has rescued 67 lorises in the past 12 years. A majority are from north Bengaluru, particularly in and around IISc — another sign this could be lorises’ last viable habitat in the city. Of 19 cases where causes of injuries were studied, just two cases of starvation and stress were linked to the use of lorises for black magic rituals. The rest were due to electrocution, dehydration, injuries to the body perhaps due to a fall, and displacement in dense residential areas.

“The only way to save them from extinction is through habitat conservation and awareness creation. We have come across so many people who do not even know the existence of a slender loris and then we have those who traffic them, abuse them for black magic,” said Colonel Navaz Shariff, Chief Veterinarian and General Manager of PfA Wildlife Rescue & Conservation Centre, Bengaluru.

Elusiveness characterises lorises. They hunt insects primarily at night, and hide in canopies during the day. In Hennur Biodiversity Park, for instance, even regular walkers seemed blissfully unaware of the primates. A Forest Department guard here says he knows of their existence only through rare, sudden movements in the canopy, but is yet to see one.

It was to create awareness and get citizens involved in the protection of the animals that the USLP was started sometime in 2014. Largely volunteer-driven, the project would conduct regular walks. These walks/surveys would see an eclectic collection of people, spanning a spectrum of professions, point their torchlights on canopies. Occasionally, a pair of glowing back eyes would stare back.

“We did see a lot of interest from people and the media. We were trying to show people that urban spaces are not dead spaces, and that people could co-exist with animals here,” said Kaberi Kar Gupta, Founder of ULSP, whose doctoral research gave crucial insight into the behaviour of lorises in the Western Ghats.

By 2017, grants were drying up, and it became difficult to continue the project on a regular basis. Currently, the project is on a hiatus. ULSP had sought to bridge some of the gaps in understanding the behaviours of lorises. How does genetic inbreeding affect the lorises? What is the average territory for lorises in cities? How far do they travel in their nocturnal hunts or for mating?

“There is so much to study about lorises and urban spaces. But, urban ecology is not a big thing in India. Lorises are not considered endangered and do not attract grants,” said Kaberi.

But considering the rapid rate of construction in Bengaluru, time may not be an ally of the lorises or of researchers interested in understanding their behaviours. Multiple roads are slated to be widened at the cost of trees, while canopy cover in residential areas and research institutions have been on a decline.

Even areas surveyed in 2015 have become concretised. Hennur Biodiversity Park, for instance, has transformed since the survey – around Rs 5 crore has been spent on beautifying and adding visitor amenities, often at the cost of trees or canopies.

“Lorises will not survive if you have small, isolated patches of manicured city parks. We still borrow ideas of urban green spaces from the West. We need to decolonise this aspect of city planning,” said Kaberi.

And lorises can be the driving force for a more holistic version of planning that recognises co-existence with urban fauna. “Slender lorises can be an icon of Bengaluru city. If you could save lorises, you could save green spaces, mitigate urban heat effect, create a healthy ecosystem for other primates and birds,” she said.

This article is part of a series on ‘Bengaluru’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity’. This is a joint project with Mongabay India, and is supported by the Bengaluru Sustainability Forum (BSF).