A short walk in any part of Bengaluru will reveal that any available surface space has been turned into parking space for cars and motorcycles – be it footpaths, area by the curb along roads, or vacant plots. Last October, the head of Bengaluru Traffic Police warned that the iconic Cubbon Park in the heart of the city was turning into a parking lot.

But motorists around the city invariably complain about the difficulty in finding space for parking. Does that mean enough parking space isn’t available?

Proposal for paid parking

This March, the Kumaraswamy government approved the Draft Management and Maintenance of Parking Rules, that would stop free parking in residential areas in Bengaluru. Instead, residents would have to pay a fee to park on the streets. The draft Rules also introduces other measures like banning street parking near intersections, metro stations, bus stops and shopping malls, and regulating parking of commercial vehicles. The proposal allows BBMP to charge a parking fee by the hour in specific parking lots; the fee would vary depending on the road category.

Introducing a parking fee on major streets has been proposed many times in the past too, only to be abandoned. But should you have to pay for parking in the city at all? Or should the government facilitate more parking spaces for free or at low rates, to discourage haphazard parking?

What is clear is that business as usual would not do. Bengaluru already has more vehicles per capita than any other city in India. When they are not being driven around, these vehicles need space to be parked. Not only is the number of vehicles increasing rapidly, the city’s population is also expected to expand, which would further increase the demand for parking spaces, especially in central areas.

Curbside parking results in stopped vehicles merging into traffic and vice-versa, inevitably slowing down traffic flow. Often, cars and motorbikes are illegally double-parked at all angles, adding to the chaos on the streets.

Moreover, Donald Shoup, economist and Distinguished Professor of urban planning at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles), USA, finds that on average up to one-third of motorists at city centres around the world are driving around looking for a place to park. Parking on footpaths not just obstructs pedestrians, but also creates a hazard for them; these vehicles tend to damage the pavement as well.

Is providing sufficient parking space the solution?

Hitherto, the argument has been that more parking needs to be provided, as more people are driving evermore vehicles. Hence, the proposed solutions have focused on the best ways to provide more parking.

A standard solution is to require commercial establishments, houses and apartments to provide their own parking. For example, in most cities across the USA, developers are required to build and maintain a certain number of parking spots by law, based on the type of development and floor area.

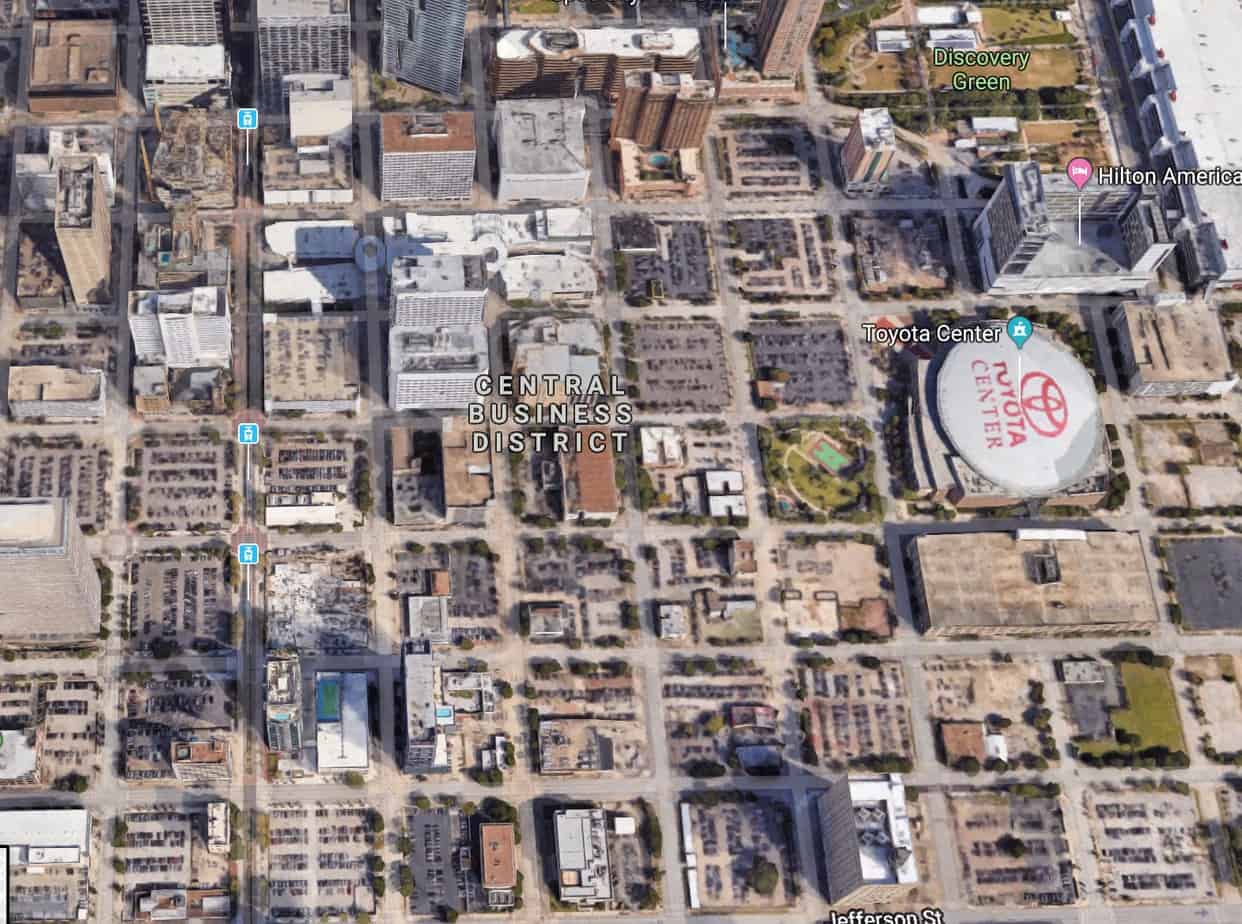

At Houston CBD in USA, surface parking dominates the landscape. Source: Google Maps

Requiring minimum parking as a pre-condition for granting planning permission for buildings has long been the policy in Bengaluru too. Most recently, the draft master plan for 2031 sets out minimum parking requirements for different types of buildings. But in Bengaluru, these regulations are routinely flouted as authorities seem unable or unwilling to enforce the rules.

Even if it can be better enforced, this approach comes with several disadvantages. First, it tends to increase construction costs, especially when land is expensive, which will translate into higher costs for apartments and for goods sold in shops. Secondly, streets lined by parking lots, rather than densely-packed buildings, tend to be unsafe for pedestrians.

Alternatively, the city could take it upon itself to build parking lots and provide them for free or at below-market rates. The National Urban Transport Policy 2014 advocates such an approach, saying, “Multi-level parking complexes should be made a mandatory requirement in city centres that have several high rise commercial complexes. Such complexes could even be constructed underground. Such complexes could come up through public-private partnerships in order to limit the impact on public budget.”

Many such multi-level parking facilities have already been built in Bengaluru, which offer parking for a fee that is very low relative to the market rent of the property. But this raises the question of whether public funds should be used to subsidise parking for motorists, especially affluent car owners. The subsidy works out to be much higher, considering that the government acquires land to widen roads, and then turns over the width of a lane to parked vehicles.

Besides, this policy runs into specific, practical problems in Bengaluru. Despite the apparent scarcity of parking space, multi-storey parking facilities in the city are mostly empty, with only 20-30% of the spots being used.

Ramesh*, a commuter who works about 500 m from the JC Road BBMP parking lot, does not park there. He says he “will have to walk from there to my workplace. Besides the parking lot is on a one-way street, so I’d have to take a longer route to park there.”

Raghavendra*, another commuter who works in the area, told me, “I prefer parking on the street near my workplace as the parking lot is not well maintained. Why should I pay to park there when I can park next to my workplace for free?” Given this, it is hardly a surprise that vehicles are found parked on the curbside and on footpaths.

Should we manage demand instead?

Prof Donald Shoup argues that increasing parking supply often has negative consequences like increase in vehicle use. Hence we need to turn our attention to managing demand instead, he says.

Prof Shoup’s idea is based on a principle from elementary economics, that if something is provided for free or at a meagre price, there is bound to be a high demand for it. But requiring people to pay for it – parking space, in this case – will reduce the demand.

Moreover, it would increase the cost of commuting by personal vehicles, and hence incentivise greater use of public transport. This in turn would help reduce petroleum consumption and pollution which have adverse impacts on health and environment.

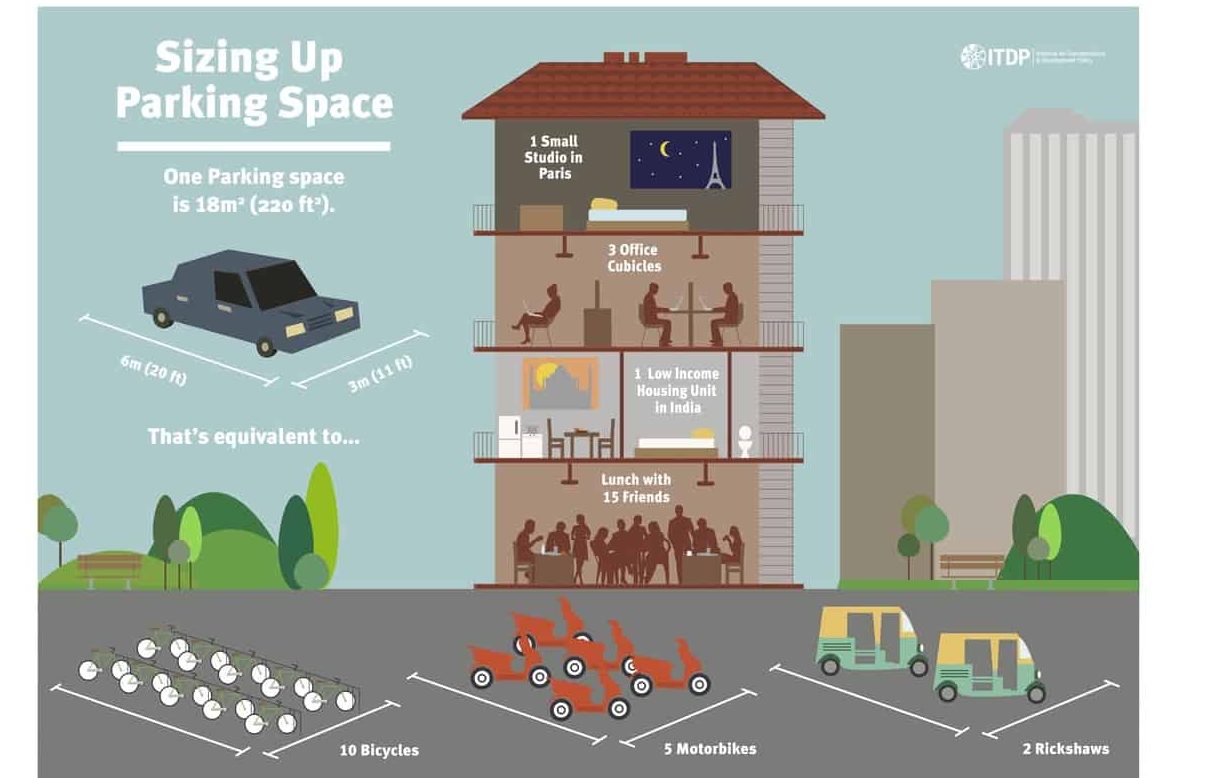

How much parking space does your car need? Source: ITDP

In his book ‘The High Cost of Free Parking’, Prof Shoup proposes a parking system using variable pricing. Here the price of parking is continuously adjusted based on demand, rather like surge pricing on ride-sharing apps. The parking fee is continually adjusted to target 85% occupancy of the parking lot. That is, sufficient space would be available for newly-arriving vehicles, but at a price that could climb steeply if the demand was high. Thus, the facility becomes cheap enough to be used, but not cheap enough to fill up completely.

An alternative to Prof Shoup’s proposal is to strictly enforce no-parking on streets, footpaths and open spaces, but to not have any other regulations for parking. Parking demand would be met by privately-operated parking garages operating like any other commercial establishment. Parking would then compete with other land uses – the relative allocation of land between parking and other uses would be determined by the relative profitability of each.

This model is the norm in most Japanese cities where street parking is mostly not permitted, even in residential areas. Residents must either park inside their own properties or rent long-term parking spaces in private parking garages that are operated commercially. In short, parking for personal vehicles is a service, rather like shared office space, wherein people pay the market price for the area they are using.

What is to be done?

In Bengaluru, we have to move away from the paradigm of increasing parking supply steadily, and instead move towards regulating parking demand by ensuring that motorists bear the full economic cost of parking. But implementing such solutions may be unpopular with motorists, as it involves asking them to pay for parking that they’ve had free of charge so far.

The draft Rules that regulate parking and disallow free parking, is a step in the right direction. But to make these proposals work, traffic laws and regulations should be enforced better. The penalties for parking and other traffic violations should be increased too. Parking fines that are 50-100 times the hourly parking rate, is not uncommon in many countries.

The need of the hour is to make citizens aware of the negative consequences that free parking has on walkability and the environment, so that they can pressure the government to ensure that the draft Rules are indeed enacted and enforced. While these proposals constitute a positive first step, more will need to be done, especially on the enforcement side to ensure the success of the policy.

[*Names of interviewees have been changed to protect identities]

Free parking or paid one would make no difference and won’t solve any problem. What must be done first is to bell the cat – the BBMP. Builders keep on building office spaces without any limitation and don’t follow any building bye Laws. Recently in Sahakaranagar I saw a five story office building being constructed on a 60×40 site. No basement for parking. Even if the basement is built, either it can accommodate only one car per story while each office on one story may have four or five cars OR the basement would be given on rent to some other business. BBMP approves buildings like this and even issued occupancy certificates. When the govt agency supposed to follow certain rules and regulations and impose them on citizens behaves in this manner, who can help the worsening situation?

Unless BBMP starts building special multi story parking lots and acts strictly against building owners who don’t provide parking in basements nothing will help.

And nowadays, most of the house owners in residential areas park their first or second or third car on the roads because there is no space inside their property. Let BBMP charge a hefty monthly rental for each car parked on the roads at night. This would compel future constructions to provide parking for own cars inside the property.