The Cooum River, once a sacred river that shaped the history of Madras, has now become a sad sign of urban degradation. For the millions of residents in Chennai, it has transformed into a malodorous, polluted, and stagnant channel, burdened with solid waste accumulation and extensive encroachments along its banks.

During a recent datajam organised by Oorvani Foundation and OpenCity, we used Geographical Information System (GIS) datasets and population analytics to investigate the underlying causes contributing to this crisis. The results show that rapid urbanisation, inadequate provision of essential civic infrastructure, and the absence of coherent policy frameworks, along with their ineffective enforcement, have collectively undermined the river’s life.

This analysis examines the comprehensive findings from the datajam, investigating the river’s intrinsic geographical vulnerabilities. It measures encroachment on the riverbank and sewage inflow and suggests policy interventions to turn things around. We primarily identified the specific locations and the extent of the Cooum River’s deterioration. The outcomes of the GIS-based analysis are both striking and deeply concerning, revealing with unprecedented clarity the principal factors contributing to the river’s decline.

An introduction to the Cooum: A river’s journey

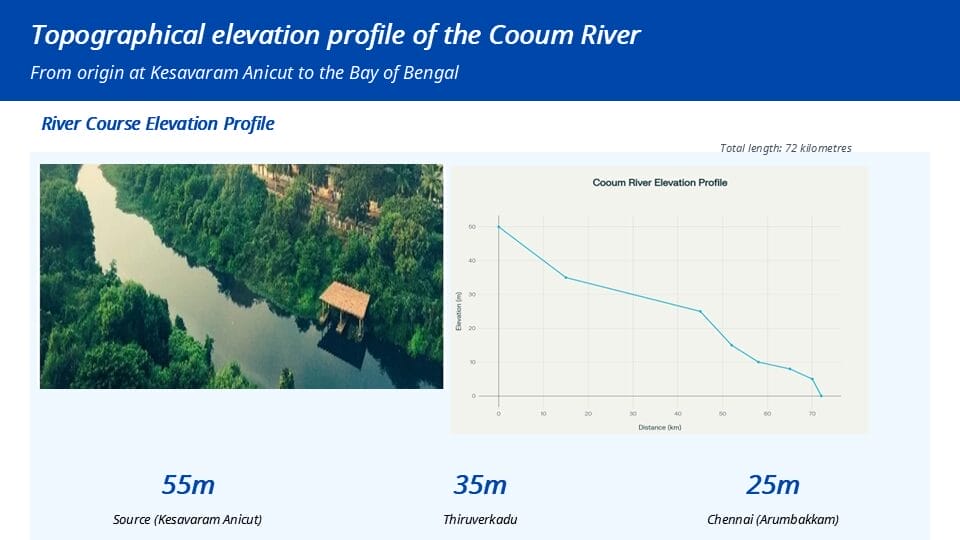

The Cooum River begins its 72‑kilometre journey as a surplus course from the Cooum tank in Tiruvallur district, not as a polluted channel. Its origin lies at the Kesavaram Anicut. Satellite images reveal that the river basin winds through a peri‑urban landscape, where multiple interconnected waterbodies form a complex hydrological network.

The river’s gentle slope is a natural weakness that contributes to stagnation. Starting at an elevation of 55 metres, it flows eastward and drops to just 25 metres by the time it reaches Arumbakkam, in the heart of Chennai, before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. Within the city, the low gradient causes the current to move very slowly, making the river far less effective at flushing silt and pollutants out to sea.

This geographical reality has always made the Cooum vulnerable to stagnation, a weakness that has been catastrophically exacerbated by rapid, unregulated urbanisation.

The encroachment crisis: Living in the “No-Go” zone.

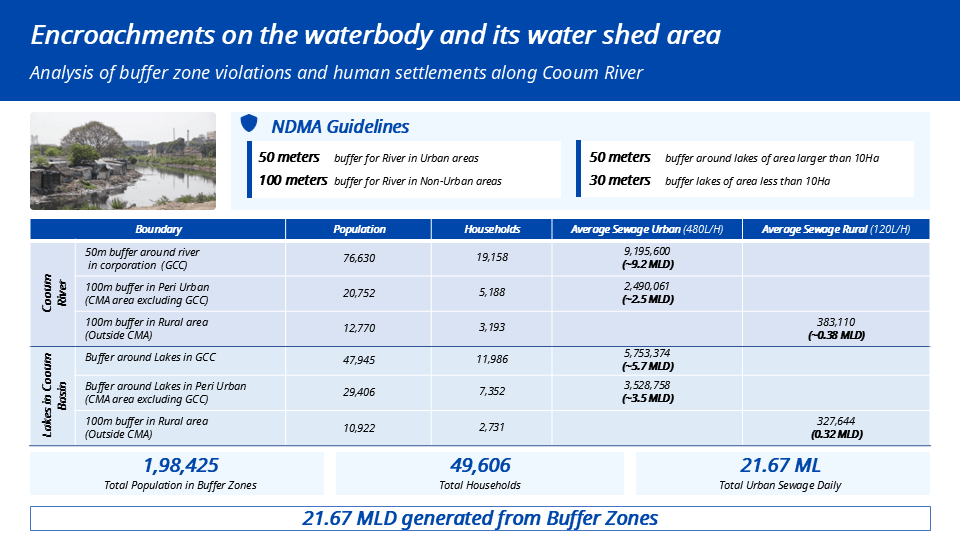

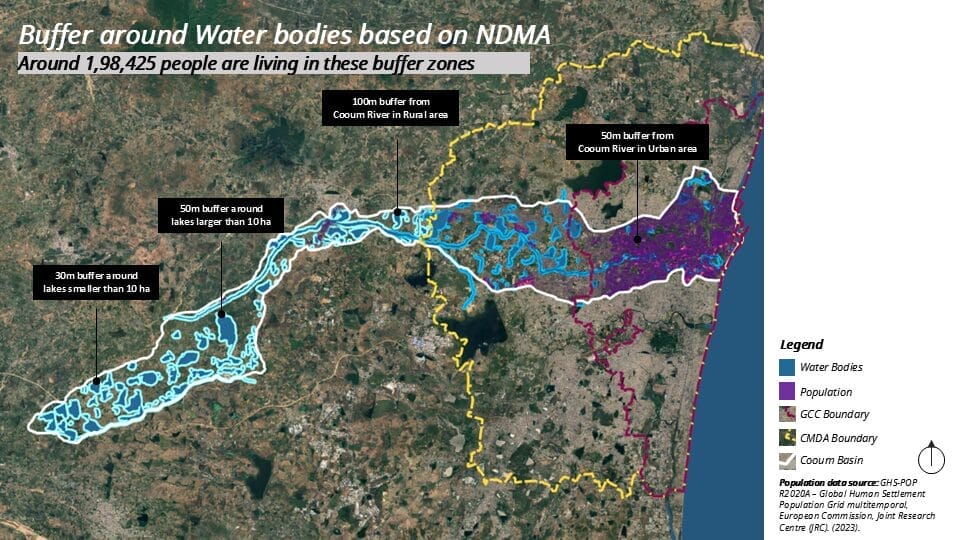

According to the guidelines of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), buffer zones must be established around water bodies to mitigate flood risks and safeguard the surrounding ecosystems. These designated areas are classified as “no-development zones,” with an advised buffer width of 50 metres for rivers situated within urban areas and 100 metres for those located outside city limits.

The findings from our analysis reveal extensive and systematic violations of these critical buffer zones, underscoring a significant lapse in both compliance and enforcement. The most important results are:

- A population at risk: An estimated 198,425 individuals, comprising approximately 49,606 households, reside within these mandated buffer zones along the Cooum River and its associated lakes. This substantial population is directly exposed to heightened environmental and health risks resulting from the encroachment into regulated no-development areas.

- Direct sewage discharge: The settlements located within these buffer zones collectively generate an estimated 21.67 million litres of untreated sewage per day (based on our calculations from population density and STP capacity data). Owing to the predominantly unplanned and, in many cases, unauthorised nature of these constructions, the majority of these households remain disconnected from the city’s formal sewage infrastructure. Consequently, a significant volume of raw wastewater is discharged directly into the river system.

This encroachment is not just an environmental issue; it is a human and planning catastrophe. It has choked the river’s floodplain, destroyed its natural riparian ecosystem, and turned its banks into a primary source of pollution.

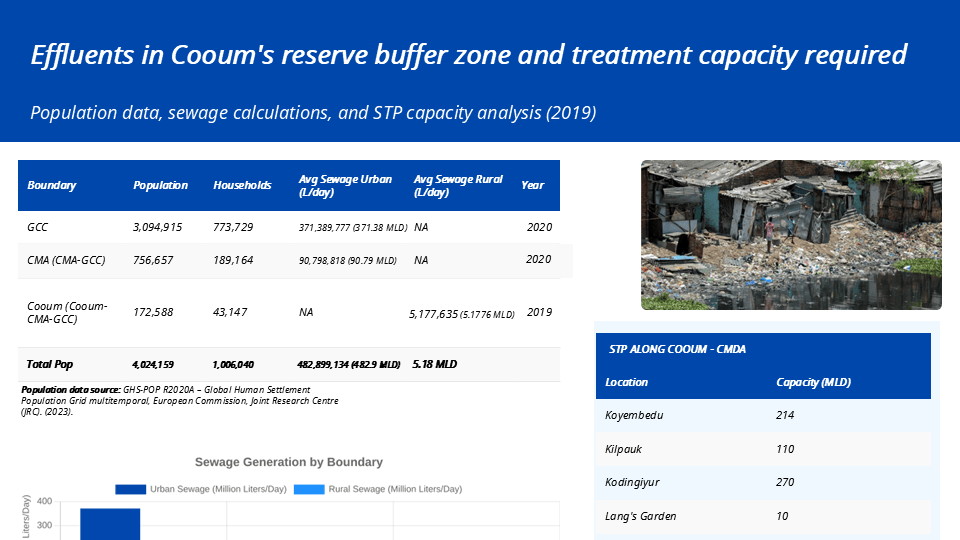

The surge of sewage and the crisis of inadequate treatment

The Cooum basin within the Chennai Metropolitan Area (CMA) is a huge source of pollution, extending well beyond the violations observed within the designated buffer zones. The study, utilising population data from 2020 (GHS Pop 2020), estimates that the combined urban and rural populations of the basin generate approximately 488 million litres of sewage per day, comprising 482.89 MLD from urban areas and 5.18 MLD from rural settlements.

The existing Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) infrastructure associated with the Cooum includes facilities located at Koyambedu (214 MLD), Kilpauk (110 MLD), Kodungaiyur (270 MLD), and Lang’s Garden (10 MLD), providing a cumulative treatment capacity of 604 MLD. However, these facilities collectively serve the broader Chennai region and are not dedicated exclusively to the Cooum basin.

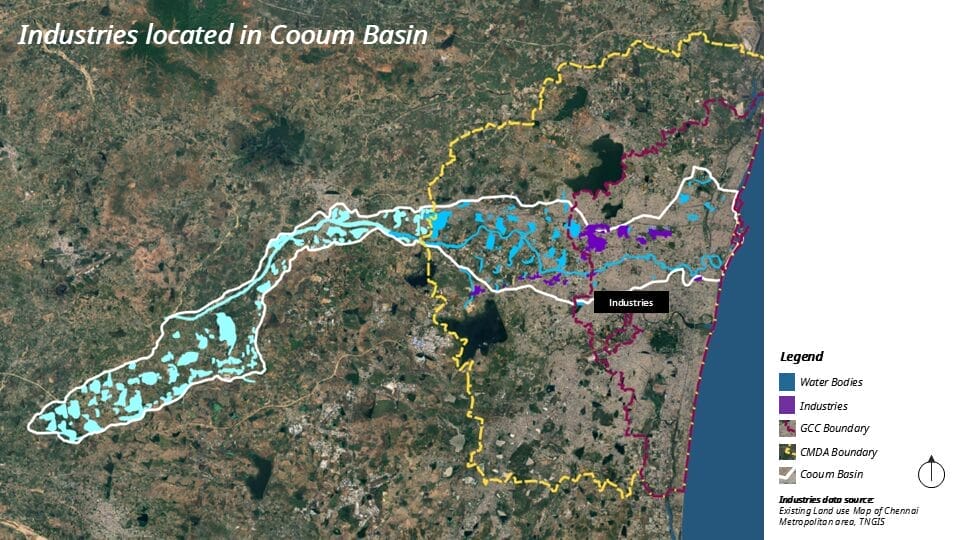

On paper, the total installed treatment capacity appears to exceed the estimated sewage generation; a substantial disconnect in sewage conveyance and infrastructure coverage results in large volumes of untreated wastewater never reaching the treatment plants. In addition, thousands of unauthorised discharge points continue to release raw sewage directly into the Cooum River and its network of feeder canals, severely compromising the river’s ecological health and undermining urban water management efforts. Moreover, GIS mapping shows that industries in the basin add another layer of toxic industrial waste to the mix.

Read more: Polluted Chennai rivers call CRRT’s restoration strategy into question

Policy failures and proposed policy interventions:

The Cooum is in its current state because of decades of bad policies and rules. Neither the Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules (TNCDBR), 2019, nor the earlier master plans for the Chennai Metropolitan Area provided clear, enforceable guidelines for development in the vicinity of water bodies.

Over the years, such policy gaps and regulatory lapses have been systematically exploited, boundary notifications were altered, zoning norms were diluted, and natural drainage channels were reclassified as buildable land. These failures have collectively facilitated the extensive encroachments visible today along the Cooum and its tributaries.

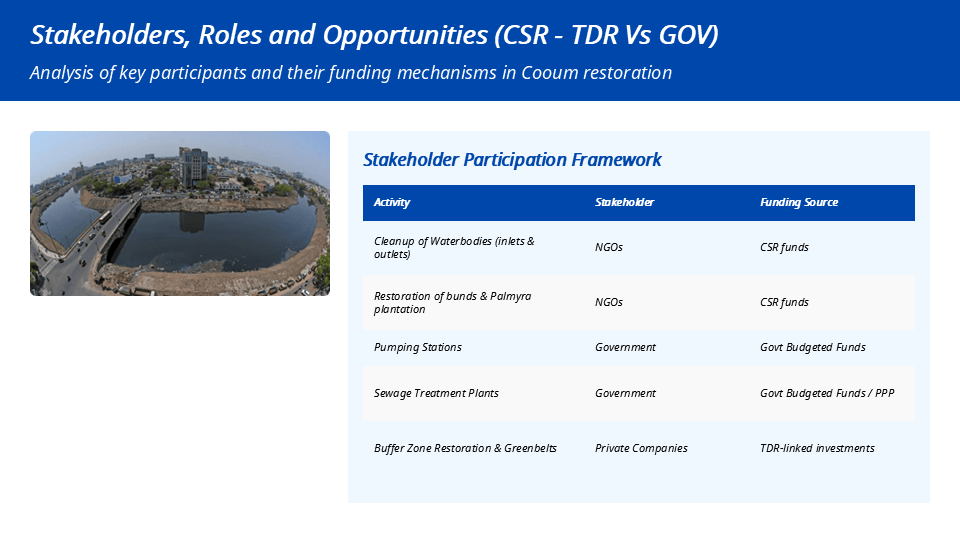

During the datajam, we created a policy framework that looks to the future and is meant to attract private sector efficiency and investment. This is because a purely government-funded approach is not enough. This model, with many stakeholders, suggests a clear division of roles:

- Government: Focus on large-scale infrastructure like STPs and pumping stations, funded by state budgets or Public-Private Partnerships (PPP).

- NGOs: Continued implementation of community-based interventions, including micro-cleanups, public awareness initiatives, and afforestation programmes, financed primarily through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) contributions.

- Private Companies: Assume an incentivised role in the restoration, protection, and long-term maintenance of the river’s buffer zones, under clearly defined contractual and regulatory frameworks.

A key part of the proposed policy framework is creating a “No-Development Zone” marked by a “Protected Blue Line” to stop encroachment, protect ecology, and manage riverbanks sustainably. Transferable Development Rights (TDRs) offer a strong incentive.

- Goal: Restore and enhance river buffer zones into eco-friendly, public spaces.

- Participation: Government identifies restorable areas; private entities bid to take part.

- Process: Selected entities restore and maintain their stretch for 10–20 years, tracked via a geo-tagged public registry.

- Incentive: On verified completion and upkeep, as confirmed by independent third party audits, entities earn TDRs, redeemable for extra Floor Space Index (FSI) in designated city zones.

- Penalties and protection: According to the framework, non-maintenance leads to TDR revocation; fraud results in blacklisting, fines, and legal action. Oversight is ensured by an Independent Supervisory Committee and citizen grievance system.

- Legal foundation: Requires amendments to the Tamil Nadu Town and Country Planning Act and the Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules (TNCDBR), 2019, for legal and technical implementation.

Read more: Pallikaranai at a crossroads: Expert warns of irreversible damage to Chennai’s last great marshland

A data-driven hope for the revival of the Cooum

The analysis revealed clear insights into the Cooum River’s crisis, including widespread encroachment, high sewage levels, and major flaws in Chennai’s wastewater system. Restoring the river is a tough task due to its complex natural geography and years of urban neglect.

Experience has shown that government-led interventions alone are insufficient to achieve lasting ecological recovery. The proposed policy framework based on Transferable Development Rights (TDRs) offers an innovative, pragmatic approach—introducing a market-based incentive that aligns private sector investment with environmental restoration objectives. By linking profit to ecological performance, the model fosters shared responsibility across government, private entities, and civil society.

Ultimately, the success of this initiative will depend on strong political commitment to enforce the ‘Protection Blue Line’, remove encroachments, and prioritise investment in last-mile sewage infrastructure to eliminate the thousands of illegal discharge points polluting the river. The data has given us both the diagnosis and the prescription; what remains is decisive collective action. Now, the city’s planners, policymakers, and residents need to take action to bring their sacred river back to life.