A recent (2019) survey of mobility practices among India’s urban population by the New-Delhi based Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) found that 37% of respondents used public transport more than once a week. A vast majority of the people travel distances less than 10 km for work and education, and walking continues to be the most dominant mode of transport for urban India.

The study, which captured all the modes used by individuals in a week, revealed that two wheelers were the second most preferred mode of transport, followed by public transport. Strikingly, the share of people relying on two-wheelers was much higher in Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities, which have limited public transport services compared to metro cities.

If these figures are any indication, the restrictions and limitations on public transport commute in the aftermath of COVID-19 could mean that we may see even more people shifting to private two-wheeler use and that ridership levels for buses may not recover to pre-COVID levels anytime soon.

The Bangalore Metropolitan Transport (BMTC) has witnessed an increase in bus ridership post lifting of lockdown; however, at 10 lakh daily commuters as of mid-June, it has recouped only a fraction of the demand it saw during pre-lockdown days, which averaged 35 lakh daily commuters.

This is perhaps expected as public transport appears to be the very antithesis of physical distancing. At the same time, public transport is also the lifeblood of a local economy. How does one reconcile this dichotomy created by the pandemic, and ensure increasing use of public transport in the cities?

Necessary interventions

Firstly, operating buses and metros at near pre-COVID-19 levels of service and ridership in Indian cities, while preventing virus transmission, needs two critical interventions:

- Flattening peak ridership demand

- Enforcing the use of masks and civic hygiene by commuters and transport operators

Staggered timings for educational institutes and offices can level out the morning and evening peak demand for public transit and prevent overcrowding.

While mandates for wearing masks are already in place in most states, awareness and practice of personal and civic hygiene while commuting should be emphasised alongside disinfection protocols for all transit systems. London and Seoul have resumed public transit operations and have made masks mandatory along with punitive measures for non-compliance, including fines.

Secondly, policymakers and transit operators need to dispel transmission fears and build trust again in the mass transport system to prevent sustained loss of ridership. Thorough and constant communication on Standard Operating Protocol (SOPs), adherence to the same, third party monitoring, and sharing of evidence with the public regularly could do this in the short term.

Health experts, policymakers, commuters and service providers need to engage on the risks of COVID-19 spread via public transit at various public fora to dispel myths and encourage individual hygiene practices.

Adapting operations and finances

Reducing transmission risk in public transport has direct and indirect costs. Regular disinfection and transport cleaning will double the time spent by buses at terminals. Implementing frequent and continued cleanliness will need more human resources.

Maintaining physical distancing while boarding and alighting buses and metros will increase the dwell time. And running a sustained campaign on educating citizens on the safety of public transit too will need additional financial, human and infrastructural resources.

So how can we create access to resources and also encourage greater numbers of commuters to turn to public transport?

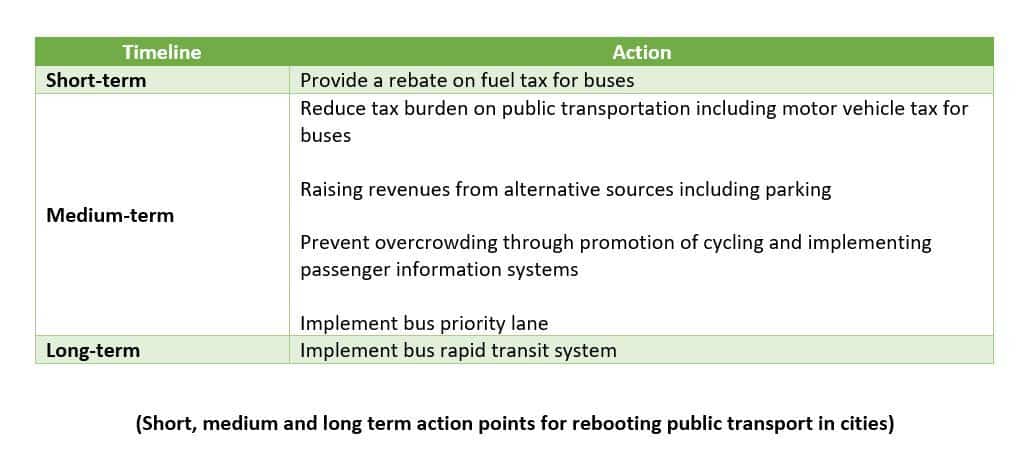

1. Provide a rebate on fuel tax (near-term): The combined state and central tax on fuel is as much as 69% of the total fuel costs in India. While this is an effective carbon tax for private vehicles, public transport buses could get a rebate, especially at a time when state transport undertakings (STUs) are financially stressed and have no relief packages announced for them.

2. Pruning taxation on public transportation (mid to long-term): A GST of 5% is levied for air-conditioned contract and stage carriage vehicles (like AC buses) on the ticket fare. Further, the motor vehicle tax is calculated based on seating capacity, engine capacity, cost price and other factors. For instance, private bus operators in Karnataka have to pay INR 3895 per seat per quarter as motor vehicle tax..

To alleviate some of their financial stress, bus operators in Kerala were recently given a 30% relief on the quarterly tax by the state government. Similar pruning or rebates on direct and indirect taxes for an asset and service that creates a social good ought to be considered because higher transit fares can lead to distributional effects.

3. Raising revenues from alternative sources (mid to long-term): CEEW’s assessment shows that if North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) were to convert free-parking sites under its jurisdiction to paid parking, 94% additional revenue could be generated. Cities can direct this amount to improve public transit and also acquire more buses.

Among the beneficiaries of public transit services are businesses whose employees can commute to and from offices. Companies tying up with transit agencies to provide subsidised metro and bus passes for their employees can encourage non-captive users to start using public transit, creating a new revenue stream from these businesses.

4. Preventing overcrowding (mid-term):– With staggered school and office timings, cities and states should also promote cycling and walking for short trips. Passenger information systems based on SMS and WhatsApp could be deployed on priority basis for journey planning.

5. Implementing bus priority lane and BRT (mid to long-term): Bangalore provides a shining example of an infrastructure-light intervention to improve the speed of buses within the city in the form of the bus priority lane. A fast-tracked process for the same across cities is the need of the hour to circumvent the time lost due to increased terminal turnaround and dwell time.

In the longer run, however, Bus rapid transit (BRT) systems in cities must allow for cashless and off-board ticketing, improved speeds, an increased overall level of service with increased numbers and frequency of buses, and passenger information system for trip planning. These features are particularly suited to the current SOP requirements, which differ from city to city.

Renewing trust in the public transport system will require an improvement in the quality of service offered to citizens, and implementing BRT across cities is an essential step in that direction.