The habits of birds have long been studied to make sense of the changes and trends in our natural ecosystems. Given that these are environmentally adaptive creatures — whose patterns of migration and breeding change as the ecosystems change — watching birds can teach us many things about climate change, ecological degradation and the ways we can respond to these phenomena.

Every year during Pongal time, birders and nature enthusiasts around Tamil Nadu participate in the Pongal Bird Count, a state-wide annual bird monitoring programme, which is an initiative of the Tamil Birders Network. This year as a part of Pongal Bird Count 2024, Suzhal Arivom, a group of volunteers engaged in advocacy around environmental and climate issues covered eight districts in Tamil Nadu, where 64 wetlands and ten hillocks were surveyed. Our main sites of study were lakes, tanks, marshlands, rivers and canals.

Part of the survey was also conducted in Chennai and Chengalpattu — in water bodies around Pallikaranai and Muttukadu. Our surveyor in Chennai, Chandrasekaran, used binoculars to identify birds along the water bodies, after which he physically counted birds and recorded them on a platform called eBird.

The findings from these surveys reveal many new roosting and breeding sites in and around Tamil Nadu’s water bodies. We also observed a connection between low avian populations and the presence of ‘linear intrusions’ — a term used to describe urban infrastructure that cuts through the natural ecology, such as roads, bridges and more.

Key findings from the study

- In a very small tank, Aruvankorai Lake near Kolapalur, Erode, a surveyor found both yellow and red-wattled lapwings nesting.

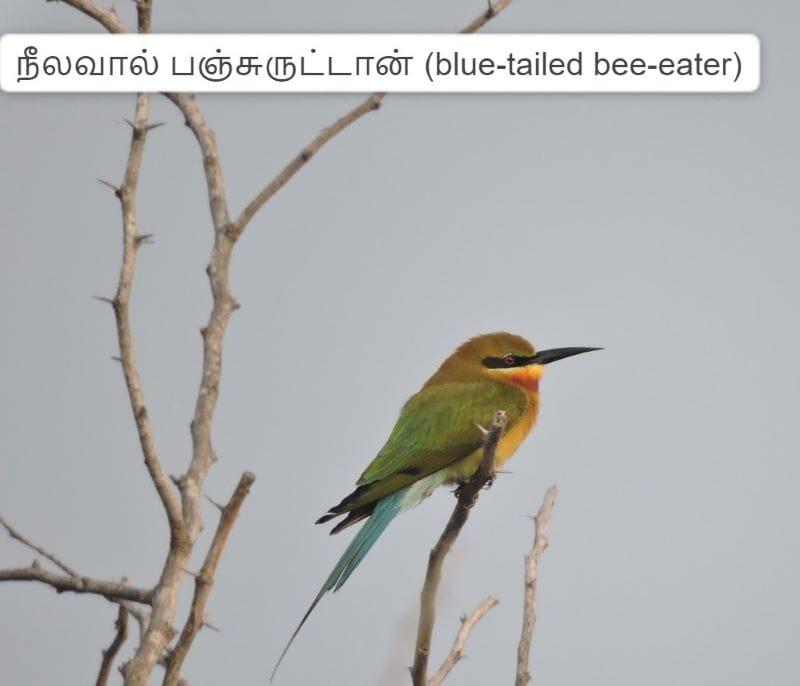

- In another lake in Erode with dry thorny trees, nearly two thousand Blue-tailed bee-eaters were found roosting. Interestingly, the birds resembled the leaves of these trees.

- In another lake with good bush and shrub vegetation, we found around 150+ Night Heron families with sub-adults along with their parents.

- We also recorded a large group of Darters and White-faced Ibis roosting in trees near a lake in Elathur.

- We also identified a congregation of 250+ Northern Pintail and structural murmurations of nearly three thousand Little Cormorants over a lake.

- There was a rare sighting of a Bonelli’s Eagle nesting in Nagamalai hillock.

Read more: Oil spill in Chennai’s Manali area can cause irreparable damage to Ennore Creek wetland

What stood out during the survey

The bird count revealed a change in the migratory patterns of ducks at the places we survey regularly. It seemed that the Northern Pintail numbers had increased and the Garganey numbers had gone down, compared to the last three years of our study.

Many of the wetlands, lakes and hillocks that we surveyed were known to have flora-fauna diversity. However, this year the ecosystem appeared visibly depleted by linear Intrusions when we visited. Interestingly, many of these may have been constructed without any proper Environmental Impact Assessment. In the hillocks where many linear intrusions were found, the avian fauna diversity was very low despite good flora diversity.

Invasive plant species were found in excess in many of the wetland areas. They were mostly seen on shores and bunds. In particular, we could see Chromolaena Odorata spreading rapidly followed by Lantana Camara (Unni) along with existing Prosopis juliflora (Seemai Karuvelam).

We also observed large-scale pollution in and around many lakes across the state. There were instances of open defecation in several lakes; many of the lake bunds in rural villages were used as garbage dump yards; the urban lakes had polluted inlet water. We also witnessed extensive fishing, and the presence of stray dogs chasing wild birds.

What we observed in Chennai

The survey in Chennai took place along two lakes and two wetland areas: Perubakkam Lake, a lake inside an IT park, the Karapakkam wetland area, and the Muttukadu backwater wetland. Our surveyor, Chandrasekaran, walked along these water bodies, binoculars in hand, stopping by areas where bird concentrations were high. He counted birds that were in the water, perched on trees and flying above. He also recorded birds whose calls were heard but not seen. On the Babaji Vidhyashram side and inside the IT park he made his count by standing in a few places, where the view was clear for the entire lake and counted birds.

Field notes from Chennai’s Sholinganallur:

In Sholinganallur, he walked along a stretch from Mohammad Sathak College up to the HCL bus stop at a slow pace. The first lake he surveyed was Perumbakkam Lake. It is a huge water body of varying depths, however, most of the time it is shallow. It usually starts from Sathak College and extends up to Global Hospital, where the land is marshy with grasslands.

Next, he looked at a lake inside an IT park in Sholinganallur, a lake that is mostly perennial and much deeper than the one at Perumbakkam. He then explored the marshlands of Karapakkam, composed of tall grass amidst building clusters.

Key findings:

- Large numbers of Northern Pintail, Eurasian wigeon and Northern Shovelers.

- Few Garganeys compared to previous years.

- Decreased numbers of Indian Spot-billed Ducks and just two Fulvous Whistling-Ducks

- The Little grebe and Marsh Harrier, earlier seen in these locations, were not spotted.

Given that this was a one-day survey, no sweeping conclusions could be drawn, however, the birds that Chandrasekaran mentioned as significantly low or negligent in the count, were usually seen by him on past occasions around the same time of the year.

Read more: Photo Essay: Tell me this is not a wetland!

Spot-billed Duck, Fulvous Whistling-Duck and Little Grebe are resident birds often seen breeding in Perumbakkam Lake. Garganeys are migratory ducks that arrive first during this season. Marsh Harriers are raptors that usually follow the water birds, which are their prey during migratory season.

We noticed widespread pollution around the water bodies. In Perumbakkam, garbage was dumped inside the lake. In Sholinganallur, the Metro Rail construction and road expansion have caused significant intrusion affecting the bird count in the area.

According to Chandrasekharan, the construction has intruded into the wetland area, where ducks and Pheasant-tailed Jacana used to breed. With time, the wetland has shrunk considerably. He also noticed large-scale growth of cattails — an invasive plant — in and around the shores of all three lakes.

Field notes from the Muttukadu backwaters:

He then proceeded to survey the Muttukadu wetland area, through which water from Pallikaranai marshland drains into the Bay of Bengal. This is a saline wetland that connects to the sea — its water levels often change, along with the tide movement. Along its shores, there are trees, grasslands and bushes. When Chandrasekharan went there, it was the start of the high tide and water levels were increasing, covering open patches of land where smaller shore birds usually forage.

Every time this happens, the water body receives marine organisms such as fish, crabs and molluscs. The influx of these creatures attracts a large number of wetland birds such as storks, cormorants, kingfishers, gulls, terns, ibises, spoonbills, egrets, herons, and migratory shore birds.

Key findings:

- Caspian terns were found in large numbers, actively foraging.

- Plenty of Great Egrets were spotted.

- Due to thick smog, visibility was poor during the low tide.

- As the tide was rising when the smog cleared, there weren’t many shore birds.

- A group of 150+ small shore birds were seen performing murmurations.

- Huge numbers of unidentified flocks were seen flying overhead.

- Great Cormorants were seen flying overhead in large flocks.

While there was some fishing taking place in the backwater areas, this didn’t seem to affect the food availability for the birds.

Recommendations from the survey

While the survey has helped us discover many new breeding and roosting sites, it also calls attention to the link between pollution, urban intrusions, and bird populations.

Findings from Chennai, especially those from Perumbakkam, point to a need to preserve whatever is remaining of our wetlands. The Forest Department should acquire the wetlands that have been allotted to private or government parties, to prevent unchecked concretisation, garbage dumping, open defecation, and more.

The survey also emphasises the importance of citizen participation in adding to scientific data through citizen science platforms like eBird, INaturalist and more. In the long run, more data can help conserve the places that require protection.

There appears to be a lack of awareness among urban residents about natural systems such as wetlands and hillocks. Many see water bodies as garbage dumping grounds and hillocks as wastelands. This perspective needs to change; with the climate crisis looming large, we need to view and preserve water bodies as a valuable source of water and as a home for precious flora and fauna.

Also read:

- Enter the jungle: Where in this busy city would you find 150 species of birds?

- Why Chennai’s young bird watchers are much more than just that

- Lessons from the past must guide the restoration of Chennai’s lakes

[The article was written with assistance from Savitha Ganesh, Engagement Associate at Citizen Matters Chennai]

Sir, Annual bird survey to be held in 2 phase in 7th and 8th march whom i would contact to join in this survey. Kind guide us

raphael

9385892303