Mission Antyodaya database aims to create granular data for gram panchayats across districts throughout the country. The intention, as stated in Union Budget 2017-18, is to create a convergence and accountability framework by tracking the various development indicators across Gram Panchayats (GP). In Karnataka, the database provides information about infrastructure and schemes at the household level.

I analysed the indicator of ‘Piped Water Connections’ across gram panchayats in Bengaluru. Under the ambit of Jal Jeevan Mission, the State government intends to achieve Goal 6 of Sustainable Development Goal, i.e., safe and affordable water for all, through provision of safe water through taps to all households, schools, Anganwadis, and other public institutions.

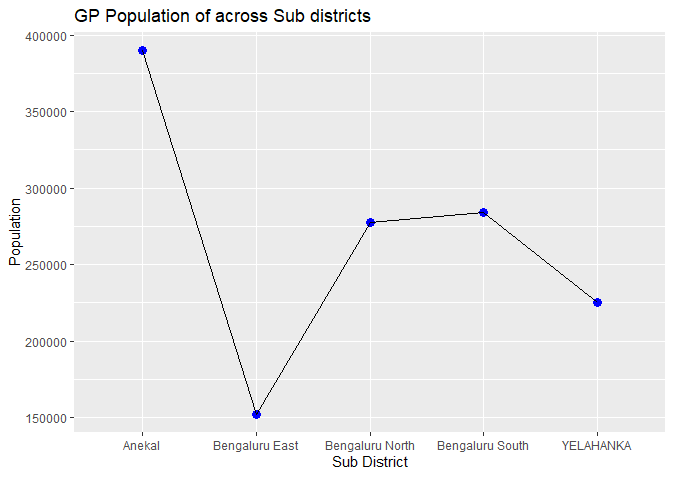

However, the data reveals skewed distribution in Bengaluru. Consider Figure 1 that describes the population of Gram Panchayats in various sub-districts of Bengaluru:

- Anekal has the highest population (3,89,712) followed by

- South Bengaluru (2,84,176) and

- North Bengaluru (2,77,516)

- Bengaluru East is the least populated, with a total population across GPs with a population of 1,52,272

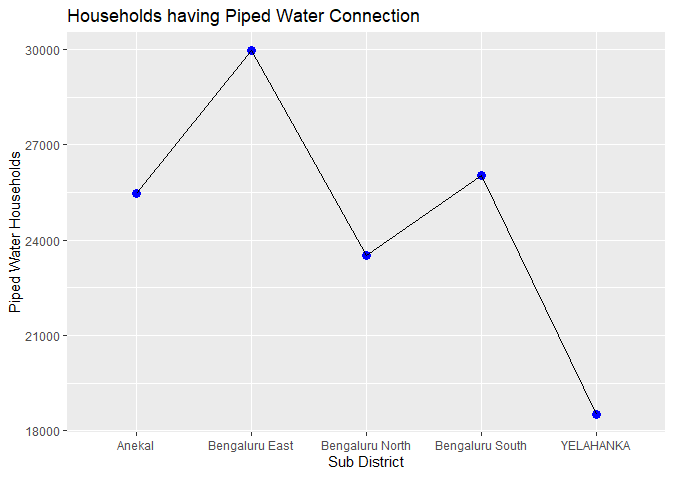

However, the population level is not corroborated with the number of piped connections in the area. Figure 2 shows the piped connections across the sub districts of Bengaluru:

- Bengaluru East has the highest number of households, close to 30,000 have piped water connections.

- Anekal, despite the highest population among the five sub districts, is at a low level of 25,475 households with piped water connections.

Read more: Will Bengaluru’s outer areas get Cauvery water anytime soon?

Skewed water distribution has been associated with unequal urbanisation. While our cities have been characterised as engines of economic growth, urban political economists have pointed out the deeply unequal outcomes these processes have rendered. This is starkly visible in the case of Bengaluru, despite state-led schemes aimed towards access, the outcomes have been different in each sub district. These inconsistencies might be due to the unequal distribution of resources and varying bargaining power of citizens across the sub districts.

An official from the Bengaluru Water Supply Sewerage Board (BWSSB) said that capacity building within the sub district is contingent on a range of social and political factors, beyond the annual budget and state-wide discourse of development. Clearly, high levels from Bengaluru East can be seen as grounded in the high infusion of capital investments and overall increase in civic capacity in the region given its popularity as a harbour for IT-firms. It might be assumed that increased industrial growth has led to increased levels of social infrastructure, while regions like Anekal lag behind.

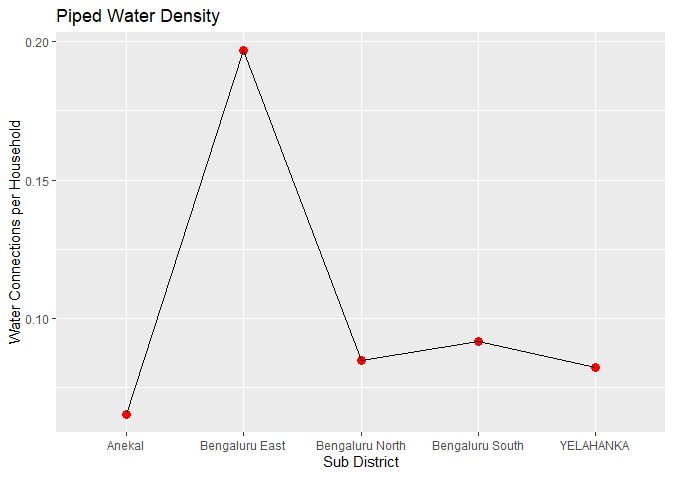

Accounting for inequality

The scale of inequitable distribution is clear when we compare water connections per unit household. Figure 3 shows Piped Water Density across the sub districts with Bengaluru East with the highest density of 0.197 while Anekal is at the lowest with 0.0654 water connections per unit household.

Read more: Why apartments in outer Bengaluru hesitate to apply for Cauvery water connection

Skewed water distribution might be seen as a symptom of the range of unequal processes that haunt Bengaluru’s urbanism. Any state that aims towards sustainable development should account for such inconsistencies. Access to piped water is linked to other capabilities, with communities deprived of water across caste-lines and subjected to other forms of deprivations such as loss of income (due to third-party water sources) and loss of productivity. Lack of piped water implies long hours of waiting for water along with the work of storing it. This arduous task is carried out by women in most poor households.

As one of India’s ‘global’ cities, Bengaluru is part of C40 coalition, a group of cities that have pledged allegiance to the Paris Agreement and its 1.5-degree Celsius target. It has made time-bound commitments across parameters, such as public transport, biofuel, sanitation, and water access. Ensuring that these commitments translate into equitable results on the ground is not only a necessity, but also Bengaluru’s only hope in order to become a more liveable city.

Citizen action

In case of water issues, you can raise a complaint with BWSSB by registering on nammabengaluru.org, you can also track your complaints here. Additionally, use BBMP’s Sahaaya 2.0 app that caters to local municipal complaints.

Very deep and appreciating study

The allocation of funds and resources in Bangalore’s south, central, and east areas is primarily influenced by politics. Long-standing MLAs who have won multiple times and retired bureaucrats residing in these locations often have a significant say in budget allocation. Interestingly, even though these areas don’t generate as much revenue as the Bommanahalli and Mahadevapura zones, they still receive a substantial portion of funds.