On his 17 km walk along the Mithi, Abhijit Waghre observed the river’s water level, its flood protection infrastructure, and associated limitations in basic sanitation services.

Read more: Walking along the 17-km long Mithi river: A look at the riverine ecosystem

Most of Mumbai’s stormwater systems depend on the Mithi river for drainage to the sea. However, systemic challenges abound, with settlements abutting the river, limiting the effectiveness of this approach during the problematic monsoon months. When high tides and heavy rainfall coincide, the city’s stormwater flow to the river gets backed up resulting in Mumbai’s annual flooding woes.

One such systemic challenge is the pressure on the capacity of the river. Typically, stormwater drains are meant to remain dry during the summer months due to no rainfall. The presence of water in stormwater drains during summer indicates inflow of sewage and wastewater which would eventually pollute the river. At Gautam Nagar, the drain connected to a stormwater outlet which flows to the river is observed carrying both solid waste and wastewater to the river.

Solid waste, hyacinth growth and desilting ramp remnants diminish the river’s conveyance capacity. Facing deficient (or non-existent) wastewater and solid waste management, households are compelled to connect their wastewater outlets to the existing stormwater drains. However, such waste inflows to the river are not just from households.

Community toilets in Gautam Nagar, Marol Shivaji Nagar and Saki Naka, in the upstream stretch, and Babasaheb Ambedkar Chawl, in the downstream stretch, connect to stormwater outlets flowing to the river as well.

A new community toilet was observed behind an abandoned toilet at Shivaji Nagar in Saki Naka. Such a situation usually stems from lack of maintenance of the existing toilet leading to its dilapidated state. As a result, a new toilet block is introduced by local politicians, instead of repairing the old one, and connecting it to a new sewage line. This leads to one more sewage outlets discharging into the river, thereby highlighting the complex nature of wastewater management needs in and around the river.

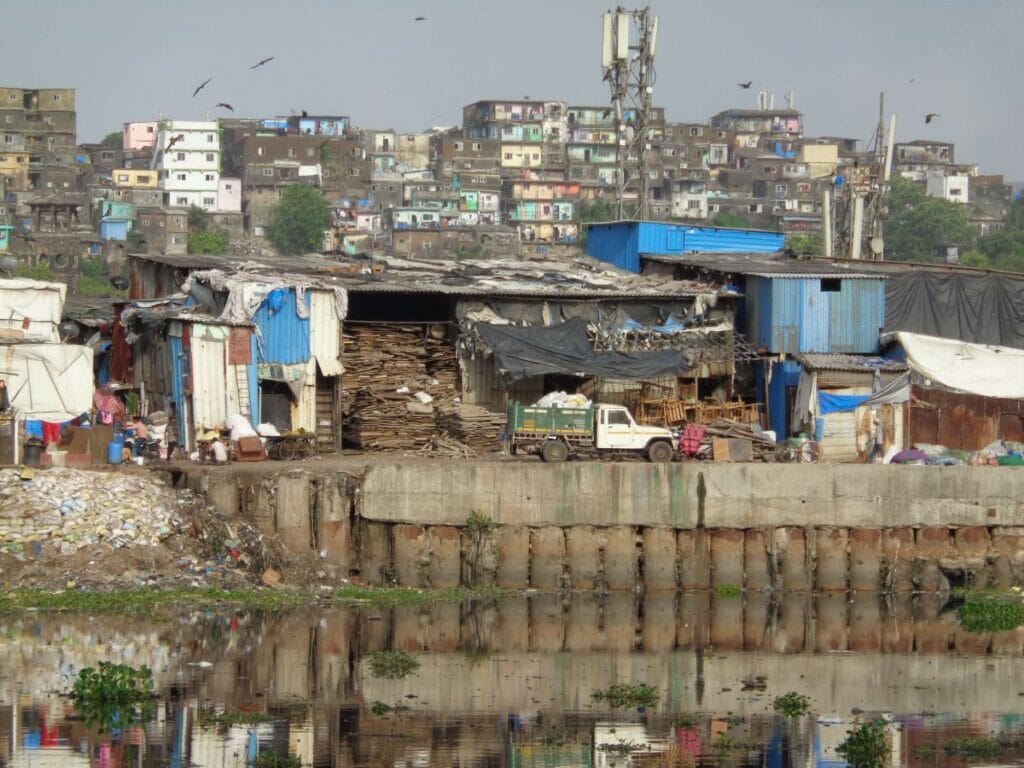

According to the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board’s Action Plan for Mithi River, 947 industries, including automobile manufacturing, plywood supply stores, hardware stores, silk mills, ready mix concrete suppliers and scrap dealers, dot Mithi’s banks.

Copious amounts of waste, from these industries, make their way into the river and end up clogging it.

Solid waste that ends up in the river restricts its stormwater carrying capacity, requiring the river to be desilted, all year round.

Read more: To clean our oceans, we need to remove plastic from our rivers

How the Mithi River impacts urban settlements

Many settlements are dangerously close to the water’s edge. One such example is at Santacruz-Chembur link road, in the downstream stretch of the river where the river is meters away from Kolivery village – visible on the left above.

Other examples are of the scrap shops, near Chunabhatti-BKC flyover and CST Road bridge, Kalina, that are exposed to high water levels through the year and are even more vulnerable during the monsoon months.

Space constrained Mumbai, witnesses competing demands from housing and industries, eyeing the land abutting the river. The new constructions require access to desilt or train the river.

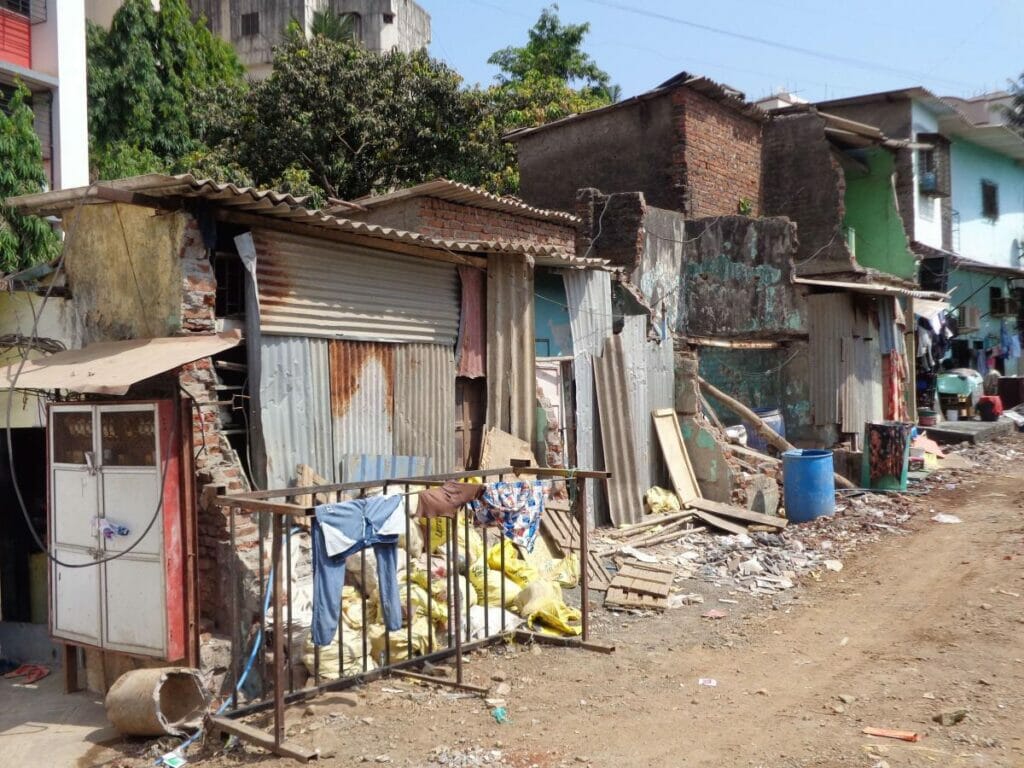

The two photos below, from Saki Naka Creek bridge and Raje Shivaji Nagar, Marol, show the demolitions of existing low-income settlements in order to gain access to the river.

Widening the river without buffers makes settlements and businesses abutting the river particularly vulnerable to floods. For example, industrial buildings in the Marol Co-operative Industrial Estate, have come 5 meters closer to the river’s edge. Additionally, sewage and industrial waste deplete the river’s capacity, intensifying flow to downstream areas.

As seen in our first photo essay, the trained river can no longer “swell” to accommodate high flows in the upstream areas, making downstream areas flood prone. Building flood resilience for the Mithi River needs a systemic approach. This includes customizing waste management for the unique context of settlements abutting the river and integrating buffer capacity to hold stormwater in the upstream areas thereby delaying the flow downstream.

The Mithi river must be allowed to function as a robust flood resilience infrastructure for the city, instead of turning into a dreaded bottleneck. City authorities must envision the river as an all vibrant, urban ecosystem, with multi-functional land use, as opposed to its current role of a drainage channel to the Arabian Sea.

The original version of this article appeared on World Resources Institute India’s blog on October 27th, 2022. Views expressed here are the authors’ own.