I was randomly browsing through my Linkedin feeds when I came across a post on a seminar advocating for inclusion of waste workers in the city’s formal waste management system. Convened by a reputed institution, the seminar had its heart in the right place, but what made me cringe was the term used to describe the people in waste. ‘Rag pickers’.

They simply got the language wrong. What’s wrong, you may ask. We all use the term ‘rag pickers’ to describe someone who makes their living out of waste – and after all they do collect some rags. Even the dictionary would define ‘rag picker’ as a person who scavenges rags and other discards for a living.

Taking the definition apart, Mansoor Ghouse, a micro entrepreneur working with waste in Bengaluru, questions “What comes to your mind when you use the word ‘ragpicker’ or ‘scavenger’ to describe the act of collecting or gathering? And here, I am asking you to describe the visual image that comes to your mind. Be honest, would the image identify the person, or would it evoke pity, disgust or sympathy, bordering on savagery, hatred, anger, or dirtiness?”

Read more: Making waste pickers’ lives better: An experience from Hyderabad

Nalini Shekar, cofounder & executive director, Hasiru Dala, adds, “The term ‘scavenger’ in India has a different meaning, it is often associated with the practice of clearing night soil and it is banned now. Internationally though, the term is often used when talking about waste picking. ”

Fluidity and constantly changing language

In 2008, the term ‘waste picker’ was adopted at the First World Conference of Waste Pickers, in Bogota, Colombia. It was critical to arrive at terminology that clearly demarcated this category of workers from others. It would also articulate a collective identity of workers, with similar aspirations across the world.

The local definition for countries might vary. In India, official terminology uses ‘waste picker’, but in unguarded conversation ‘rag picker’ is the most commonly heard term. “Lay persons, academics, officials and even journalists hear us say ‘waste picker’ but repeat back ‘rag picker’, because the language is so ingrained. And the hard truth is that these terms perpetuate caste based stigma and discrimination”, says Rohini Malur, a communication specialist.

“I feel bad when people use the words ‘rag pickers’ or ‘chapar’, as it immediately creates a strong visual; the word ‘chapar’ is given to mean ‘a person carrying stolen goods on the shoulder’. 15 years after the adoption of the term ‘waste picker’, it is sad that the old words still rule. But I also realise that things will not change overnight. It is years of social conditioning, but things change gradually and then the word seeps into our everyday vocabulary,” says Mansoor.

Language can create powerful stereotypes. Which means that the term we use to describe a community also has implications for how we treat them. And so ‘rag picker’ becomes a way to market poverty and marginalisation in the popular media and in social impact investment, removing both accuracy and the dignity we must afford all labour.

Taylor Cass Talbott, Project Officer, WIEGO, says,”The thing about language is that it changes over time; so much is constantly re-evaluated. In one sense, this makes it easier to know through language who is following the work of waste pickers, and whether they care enough to use the ‘accepted’ language.” Taylor feels, language must boil down to R.E.S.P.E.C.T. “The key here is to ask how a person chooses to identify, rather than using outdated terminology or imposing our own beliefs. The experience is personal – we are speaking of actual people, doing actual work,” she says.

Need for an empowering respectful language

Lakshmi Narayan, co-founder of SWaCH Cooperative in Pune, says “It is important to reclaim language. However, we need to understand that terminology evolves, as it should, with changing politics, aspirations and agency. In 1993, Kagad, Kach, Patra Kashtakari Panchayat (Paper, Glass, Metal Workers Association) was how waste pickers in Pune, chose to define the union, while counterparts in Latin America, adopted Recicladors and Cartoneras, depending on the contexts they operated within, as a term to define themselves.

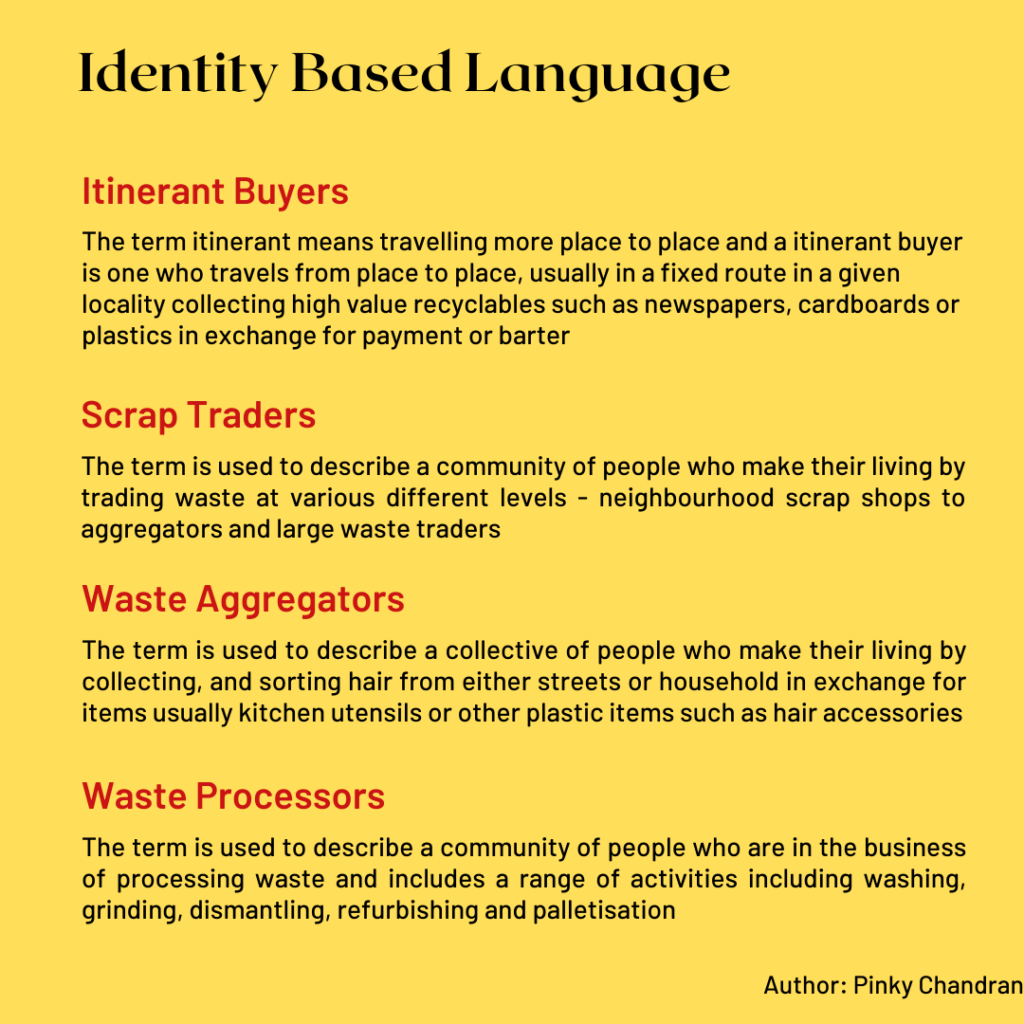

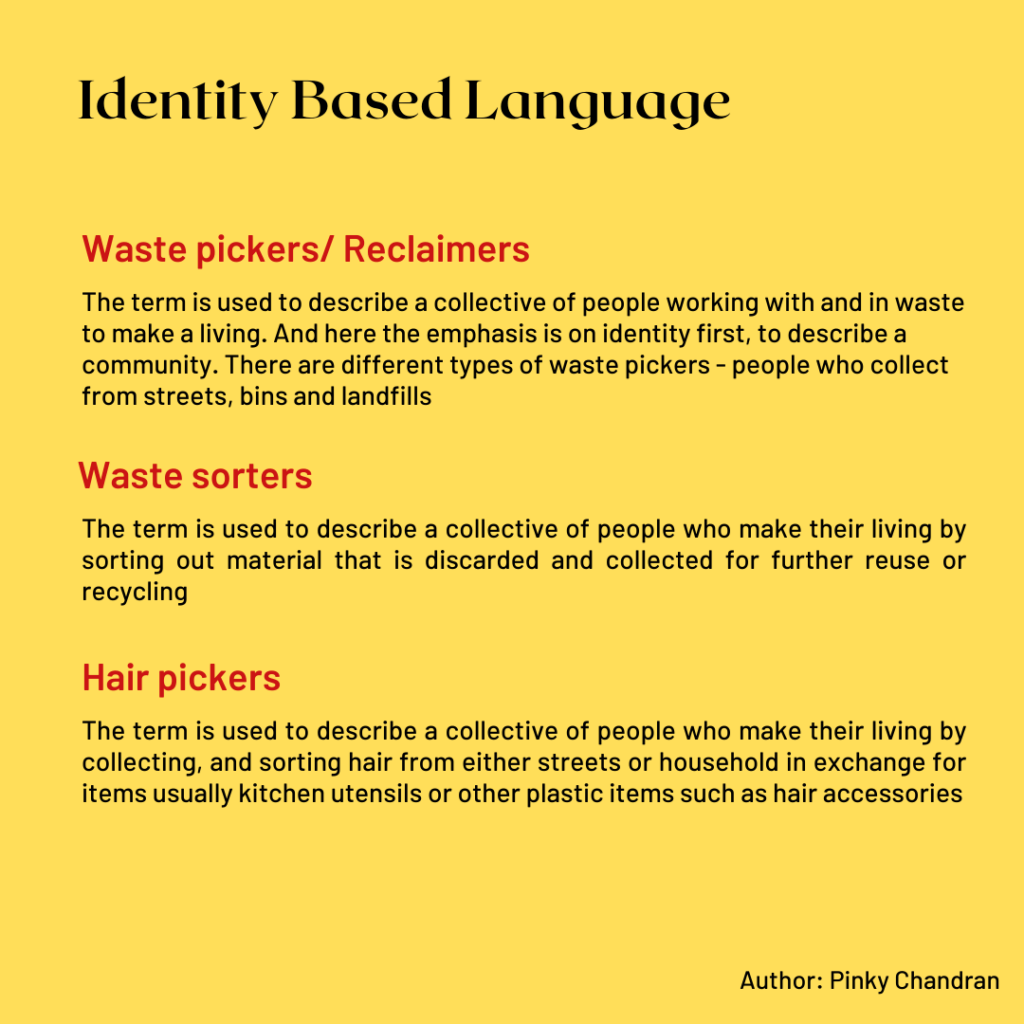

Critical to any term is affirmation and respect for their individual and collective identity, taking into account history, lived experience and pride. The umbrella definition for waste workers will thus refer to all workers who live off, or depend directly on, waste as a livelihood. This includes all those working in a formal set-up (municipality), a hybrid system (for example, dry waste collection centres) or an informal set up across the entire recycling value chain (recyclers, scrap dealers/traders, aggregators, processors etc.). But then, how does one ensure visibility for every component of the diverse workforce? The key here is self- determination and representation.

Waste picking as a work is unique, so it is important to let the community claim their identity and no doubt the landscape for waste pickers has changed a lot. Kabir Arora, Alliance of India Waste Pickers says, “Waste pickers no doubt is an English word and we don’t have a regional equivalent term.”

What emerges when one looks at global best practices is that waste pickers should decide what their occupation should be. It is their right and freedom of expression. Academicians, researchers, organisers, private sector and environmental organisations, should respect that. The right to name one’s occupation is a right of self determination of one’s identity.

“When I pick waste or sort waste, I do it with pride. Pride, because I know the value of the material that people call waste. There is an element of skill involved. We know that there are so many different categories of waste. In my years, as a waste picker and now a home based waste sorter, I am confident of at least 75 varied categories. There is much more, given the complexities and I should be recognised for that,” says Salma, a home-based waste sorter in Nayandahalli, Bengaluru.

The language of mutual respect – with an empowered workforce and communities living in dignity – can only exist when we listen to the voice of the “informal”. But as I conclude this piece, I hear the strong call for the word “reclaimers”, as none of the members of the community think of the material as waste, but as a resource.

Read more: Waste-pickers – Salvaging the city’s garbage

A checklist for citizens

A person’s identity is so closely linked to the terms we use to describe them, and so here’s a quick checklist that one can follow:

Make a list of all the slangs and outdated, offensive words: In India, there are many local terminologies used, apart from the English words ragpicker or scavenger. Check if you are using caste-based occupation tags to describe a person. For example, the use of the word ‘chapar’ not only dehumanises the person, but further contributes to discrimination, mistreatment, and oppression.

Re examine stereotypes that our culture promotes: It is important to use affirmative language, and move away from objectifying. Language is no doubt a powerful tool that also shapes attitudes. Question, if the terminologies used are empathetic or kind.

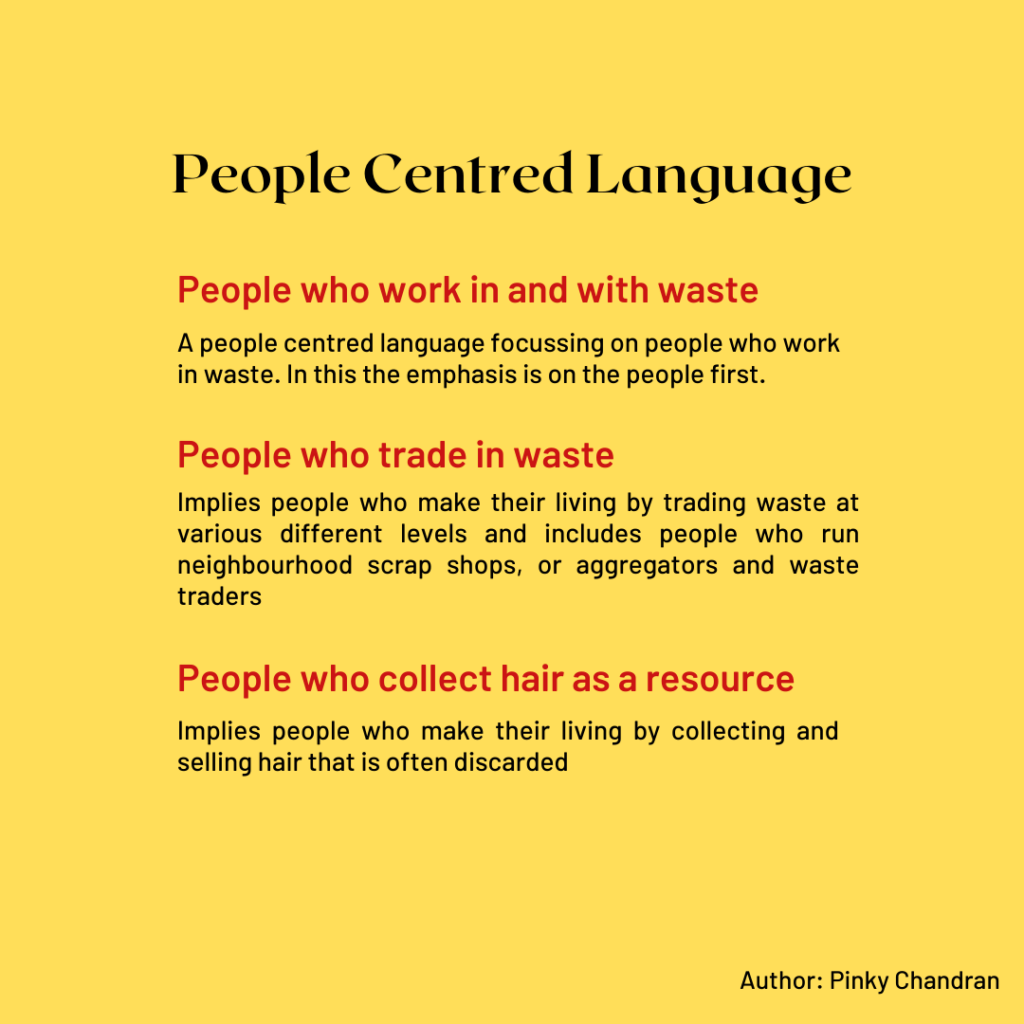

Understand the preference of individuals: The question will always remain – Person-first language or identity-first language? For example People who work in waste, or waste pickers/waste workers? ( In person-first, occupation is no longer the primary defining characteristic.)

Below is a guide we can all use:

Thanks for writing this sensitive and informative piece Pinky. I, for long thought about conservancy workers to use in cataloguing, library education and practice.