In Part 1 of this series, we saw that pedestrians are at high risk on Bengaluru streets, especially groups like children and the elderly. In this part, we look at solutions to this problem.

In the wake of COVID-19, Bengaluru, like many other cities worldwide, was put under a strict lockdown. During this time, as people stayed indoors and only left their homes to visit healthcare centers or to shop for essentials, they avoided long-distance travel. Hence hyper-local mobility increased; trips were made mostly on foot.

Car travel reduced drastically, and significant improvements were observed in traffic congestion, air quality and overall livability of the city. Studies showed a 28% drop in air pollution parameters during lockdown.

Initiatives for walkability

Before, and especially during the pandemic, Bengaluru had some significant initiatives to promote walking:

- Motorised traffic was banned on Church Street and opened to pedestrians, cycles, and e-scooters on weekends for five months, starting November 2020, under the ‘Clean Air Street’ initiative. An IISc study found significant reduction in air pollution and an increase in pedestrian and transit activity on the street over this period.

- To comply with lockdown and physical distancing protocols, the Centre’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) issued an advisory recommending holistic planning to make busy marketplaces pedestrian and cycling friendly. Bengaluru proposed implementing this in three streets – Gandhi Bazaar, Commercial Street and Malleswaram 8th Cross.

- Pedestrianisation of Gandhi Bazaar had been abandoned a decade ago due to opposition from residents and street vendors. The plan was revived in 2020 by the Directorate of Urban Land Transportation (DULT) and Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), to design this street similar to Church Street.

- Under the Smart City Project, Commercial Street was to be made a pedestrian-friendly cobblestone street. The street design is complete, but it is yet to be completely pedestrianised.

- No specific plan has been made yet for Malleswaram 8th Cross. DULT is working with consultants to design pedestrianisation here.

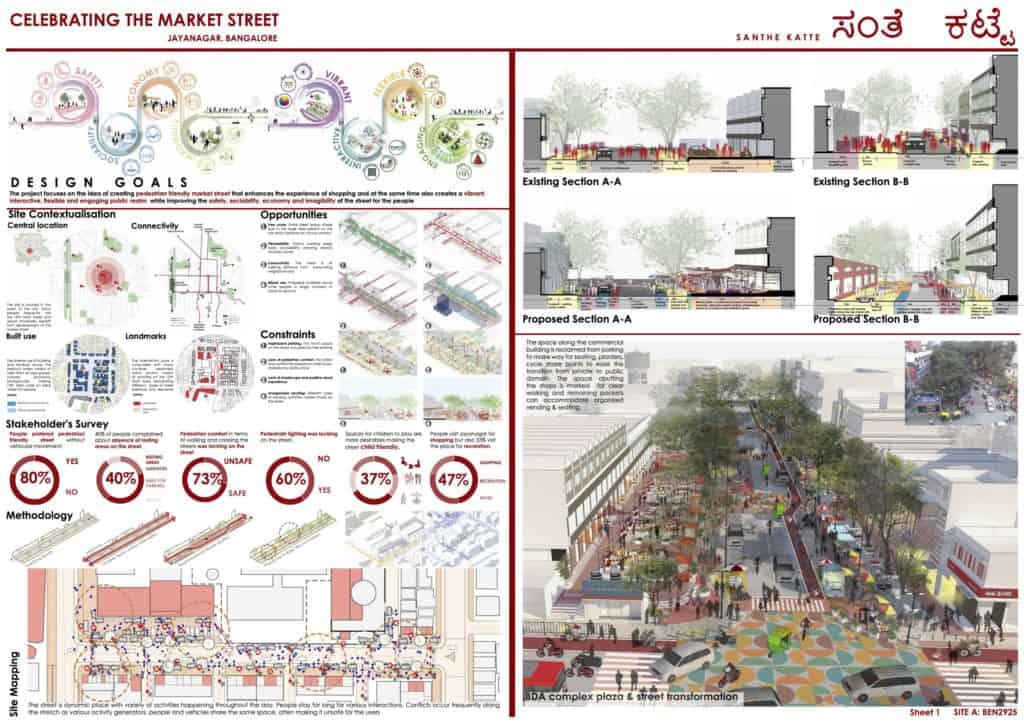

- Smart Cities Mission conducted The Streets for People Challenge Design Competition to inspire the design of quick pedestrian-friendly streets focused on placemaking and livability. The aim was to ensure green recovery from COVID-19. In Bengaluru, Jayanagar 10th Main and the neighbourhood of Wilson Garden were included in the competition.

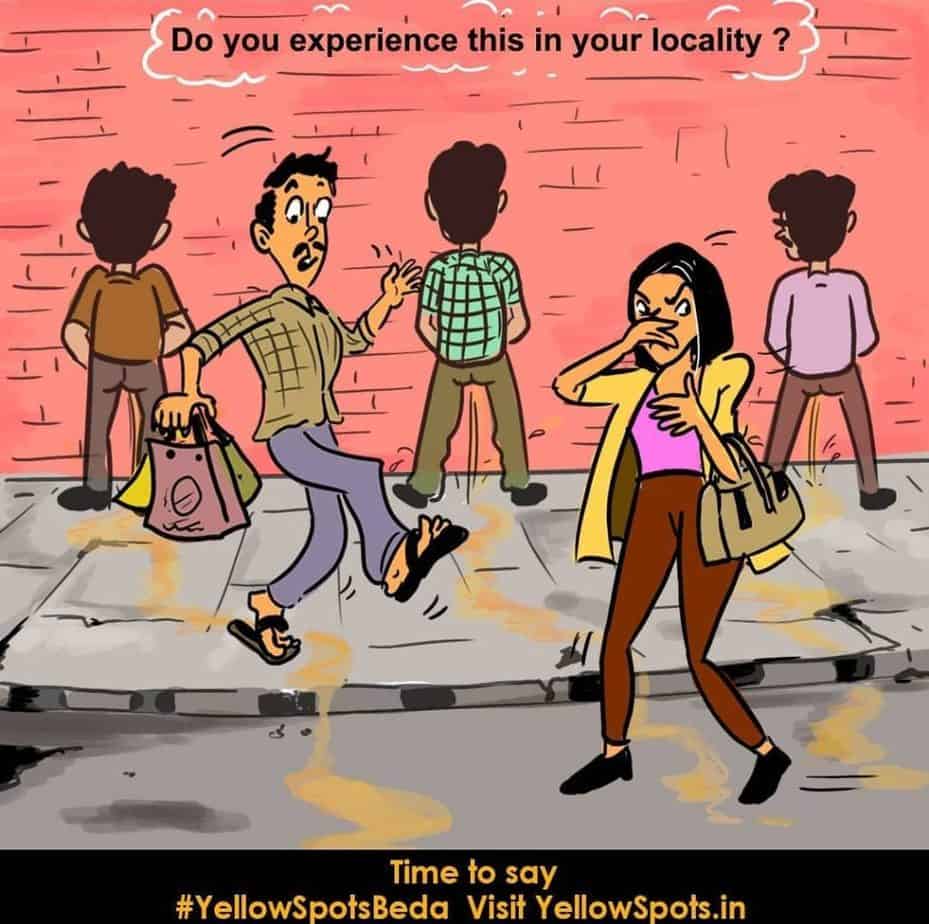

- BBMP and the NGO Janaagraha jointly launched the My City My Budget campaign in 2015 to make the BBMP budget citizen-friendly. Citizen input was solicited for issues around drivability, footpaths, health and sanitation. This year, the focus is to resolve public urination issues and to make footpaths pedestrian-friendly.

- There are also citizen-led initiatives such as ‘Eega Footpath Nammade‘ (Footpath is ours now) led by Sheshadripuram residents to bring attention to damaged footpaths, ‘Malleshwaram Hogona’ (Let’s go to Malleshwaram) by Geechu Galu and Bengaluru Moving that involves 13 artists painting murals on 12 walls to make walking the “new normal”, and ‘Footpath beku’ (Need footpaths) led by Malleshwaram Social.

But is this enough? Definitely not.

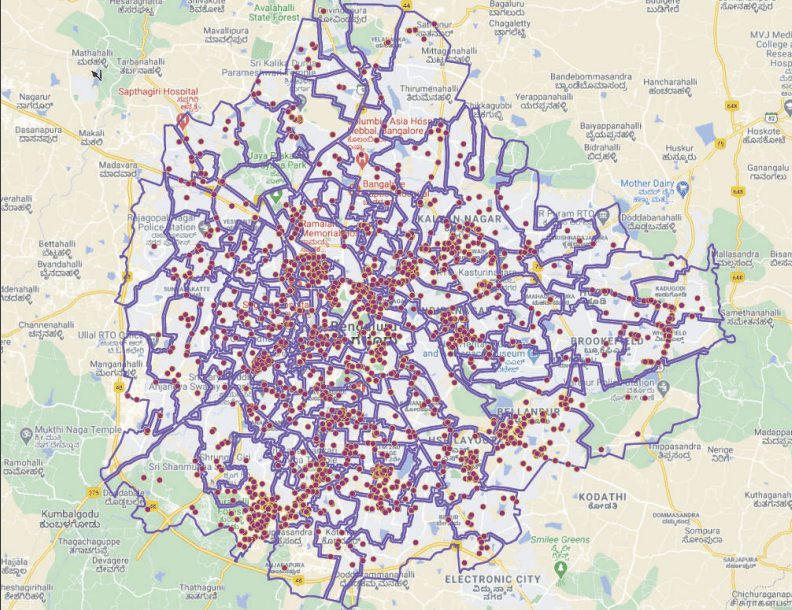

The abovementioned initiatives as well as the TenderSURE streets provide a well-designed footpath network in the city. But these are mostly focused in the CBD (Central Business District) area.

As per data from the Bengaluru Traffic Police, central neighbourhoods record the lowest number of pedestrian fatalities, whereas roads in peripheral areas such Outer Ring Road, KR Puram, Yelahanka, Kumaraswamy Layout, Chikkajala and Devanahalli have the highest numbers. The wider peripheral roads, where vehicular speeds are usually high, are a major contributor to pedestrian fatalities.

Read more: One pedestrian is killed every two days on Bengaluru’s high-speed arterial roads

Short-term and tactical urbanism projects like open street festivals, vehicle-free weekends, and street beautification efforts gave opportunities for pedestrians to reclaim their space and enjoy walking. These projects gave stakeholders a chance to explore what pedestrian-friendly streets can look like and how to implement these projects. However, piecemeal efforts looking only at one street at a time, and prioritising only the CBD and market areas, is not sufficient.

Pedestrian deaths were high even during lockdowns

Though Bengaluru was under various stages of lockdown in 2020, road crashes reduced only marginally. Pedestrian deaths still came to 164, a reduction of only 20% from the previous year. Speeding vehicles were the primary reason for these deaths. When traffic densities reduce, drivers tend to speed up. This, coupled with the lack of walkable footpaths, leads to deadly conflicts between motorists and pedestrians.

Inadequate lighting further adds to the risks after sunset. An alarming 80% of pedestrian deaths occur between 6pm and 12am, as per data from WRI’s SATS tool. Deaths are high on Sundays too, due to instances of drunk-driving on Saturday nights.

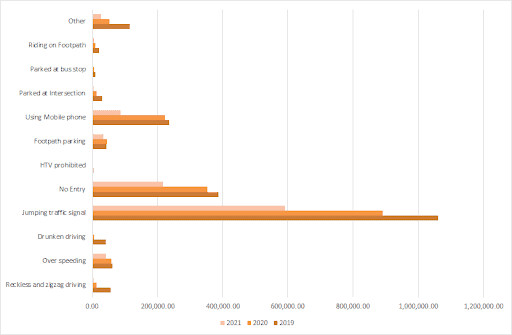

Data on motor vehicle offenses indicate other potential causes of pedestrian deaths. From the motor vehicle cases booked between January 2018 and August 2021, we can infer that jumping traffic signals, driving in the wrong direction, and distracted driving can also be noteworthy reasons for pedestrian injuries.

The significantly high numbers of 2020 is a serious concern given the city was under strict lockdown for most part of the year.

Read more: Bengaluru’s deadly footpaths: Children, elderly at high risk

Building on the momentum

As the city prepares itself for a “new normal”, we urgently need a movement to build up from the existing efforts. Lack of immediate action will result in falling back to grim trends. A comprehensive ‘Safe Streets for All’ programme will provide an opportunity to reverse the culture of car-first infrastructure, and put pedestrians and cyclists at the centre.

As stakeholders plan and design programmes, they can take a leaf out of models in other cities and countries that were also subjected to pandemic-related pedestrianisation responses as well as spikes in traffic fatalities in 2020.

Considering these models and international best practices, following are some recommendations for making Bengaluru streets safe.

- Conduct a comprehensive, equitable assessment of the city’s footpath network to identify high-casualty locations. Then address the primary cause of the casualties and the critical issues with the network.

- Bridge the gap in data. Equip local leaders and citizens with data collection tools to gather inputs and direct citizen incident reporting like in the case of WRI’s SATS tool and the My City My Budget assessment.

- Use the existing grievance redressal systems and apps managed by BBMP for citizens to report issues.

- Include last mile connectivity planning for bus stops and auto-rickshaw counters, similar to the last mile connectivity solutions proposed for Metro stations in the Comprehensive Mobility Plan.

- Integrate elements of ‘Vision Zero’ planning into all new and existing plans, like Haryana’s and Bogota’s Vision Zero Program. Vision Zero is a strategy to reduce road traffic deaths and prioritise human life above all else.

through the My City My Budget 2021-22 Assessment. Courtesy: janaagraha.org

- Further the safety assessments of vulnerable road users. Integrate safe and adequate accommodation of all users in all new and existing programmes concerning surface transportation networks.

- Indian Road Congress (IRC) or the Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act (KMC) needs to update footpath design guidelines (including width, height, frontage zones, loading and unloading zones, etc.) to meet the needs of all users. Citizen Matters had previously reported that the quality of footpath construction in Bengaluru often depends on the contractor’s whims, and no specific guidelines are followed.

- Activate a Safe Routes to Schools (SRTS) programme, similar to the Cycle to Work programme currently organized in Bengaluru. SRTS programmes bring stakeholders together to identify issues and devise solutions to make walking and cycling to school safer for children. If it is safe for children, it is safe for everyone.

- Promote low-cost but high-impact design solutions for improving accessibility for all users, such as the Ramp my City initiative (to ensure accessibility for people with disabilities) already introduced on Church Street.

- Get rid of the ‘highway-like’ feel and long stretches of signal-free corridors. If we want people to drive slow, designing racetrack-like roads will not help. Pedestrians must have the first right of access and streets must be designed to give them priority.

- Align city/transportation budgets towards designing safe and comfortable infrastructure for all users, not just cars. Avoid implementing projects that have historically proved to be inefficient, such as pedestrian underpasses and skywalks.

- Adopt the Safe Systems Approach which aims to eliminate fatal and serious injuries for all road users. This approach considers a holistic view of the road system; it anticipates human mistakes, and then focuses on reducing people’s exposure to crashes by reducing speeds and/or separating transportation modes where necessary.

- Consider following the Complete Streets Framework such that streets are designed to be safe, comfortable and convenient for all users, of all ages and abilities. Cities like Chennai and Pune have implemented these practices.

- Coordinate traffic signal timing along the entire roadway and adjacent streets, and integrate pelican crossing signals on streets with medium-to-high concentration of pedestrians.

- With respect to road infrastructure, ensure coordination and ownership among various government agencies at every step, in processes such as planning and policy making, community engagement, evaluating system impacts, setting design standards, identifying partnerships and funding sources, contracting and implementation, monitoring and enforcement, and regular maintenance.

- Provide local authorities with technical resources for road safety to adapt to local conditions. In India, the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) and World Resources Institute (WRI) provide such resources. Examples from other cities are Mexico’s streets handbook Manual de Calles, and Canada’s interactive tool for its local jurisdictions.

- Streamline projects across agencies to ensure smooth operations. Complete all repairs, such as drainage and pipeline repairs, before laying new roads and footpaths.

- During public and private construction projects, avoid encroaching on footpaths for material storage. Barricade the work area safely and provide appropriate warning signs.

- Government agencies should work closely, and also involve private and not-for-profit organizations, to ensure footpaths remain free of obstacles and have essential infrastructure like lighting and seating.

- Regularly engage the public and stakeholders to enhance awareness around road safety. Share findings to change citizens’ perception around safety, especially that of vulnerable road users. Informed engagement ensures that city projects are in line with user expectations, and users are in turn aware of upcoming changes in their neighbourhoods. This process also enhances transparency between government authorities and citizens.

- Monitor the dynamic environment and people of Bengaluru to update plans and policies at regular intervals, to keep implementation of initiatives relevant and beneficial.

Bengaluru was originally built for walking. Its narrow curvy roads are not driving-friendly in design. Today’s rapidly growing population, and the need to own a private motorised vehicle, have appropriated that space. It’s time to reverse this trend and make walking safe and joyful again.

[Views expressed are the author’s own.]