Over the past few years, rising temperatures, heat waves, and oppressive humidity have made Mumbai scorching hot. But not all parts of the city heat up equally. Life in some is more stifling than the others.

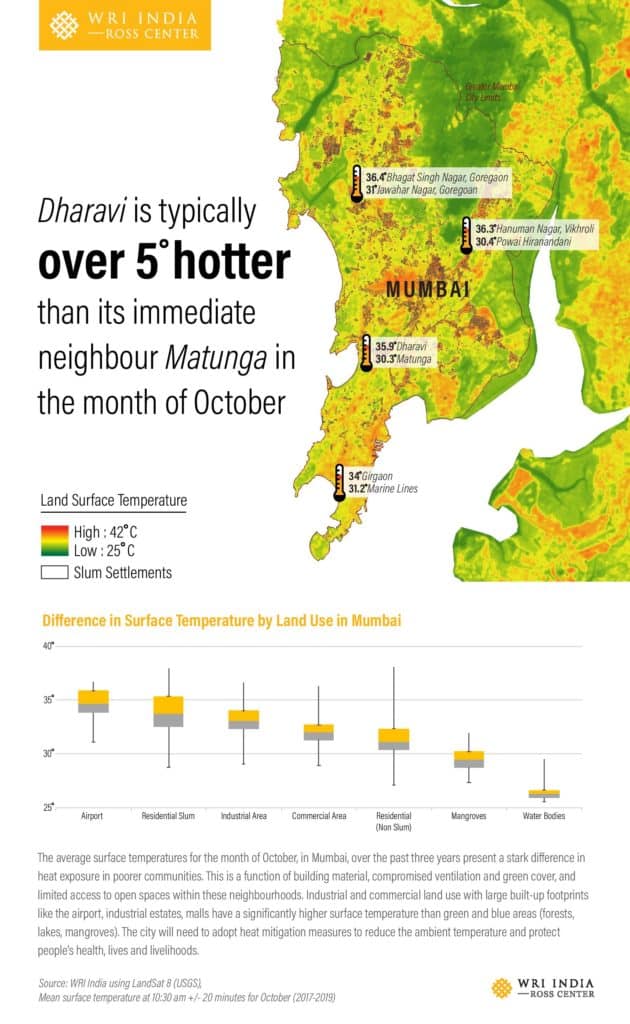

A recent World Resources Institute (WRI) infographic showed that in October, Dharavi is typically five degrees hotter than Matunga, its immediate neighbour. The study looked at Mumbai’s average land surface temperatures in October over the past three years.

Land surface temperature is the radiative skin temperature of land which is recorded using satellite-derived data. Quite simply, it is about how hot a “surface”, like a road or a roof, would feel to touch.

“Satellite sensors can observe the variation in thermal infrared radiation reflected from the Earth’s surface. They absorb a spectrum and we get the reflectance in a thermal infrared brand,” Raj Bhagat Palanichamy, Manager – Data Analytics, WRI India Ross Centre for Sustainable Cities, who worked on the study, says.

This data is processed to get a temperature, he adds, which is then visualised in shades of green, yellow or red. The greener stretches of Mumbai such as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park or the mangroves lining the water bodies have a lower temperature of around 25 degree celsius, whereas the city’s dense pockets, especially low-income settlements, such as Girgaon, Bhagat Singh Nagar, Goregaon, or Hanuman Nagar, Vikhroli reel under high temperatures, according to WRI.

“Land surface temperature drastically varies based on what kind of housing you are living in,” Lubaina Rangwala, Senior Manager – Urban Development & Resilience, WRI, says. Mumbai’s poorest communities live in densely-packed units with no open spaces, trees or foliage that can offset the heat. “Within an area, there’s a temperature difference between (housing) societies with open spaces, landscaping, or trees, and those without,” she adds. Industrial and commercial land use with large built-up footprints like the airport, industrial estates, malls have a significantly higher surface temperature than green and blue areas (forests, lakes, mangroves), the infographic notes.

The variance in temperature is broadly because of three factors: the building material (impervious concrete, asphalt and metal are known to have a higher surface temperature), access to open spaces, and green cover. Areas which are compromised on all three factors are substantially warmer than their neighbouring areas. They become urban heat islands, whose effect demonstrates another facet of inequality in Mumbai: instances of extreme heat and lower heat within the same city.

WRI is not the first organisation to study urban heat islands in Mumbai. In 2015, researchers at IIT-Bombay’s Centre for Studies in Resources Engineering, studied how changes in land use in Mumbai correlate with a change in land surface temperature. They found that the heat pockets on barren lands, slums, salt pans and concrete areas like the airport are more prominent in Mumbai.

Another study by Delhi University scientists aids in a better understanding of urban heat islands. It analysed land surface temperature in Mumbai and Delhi even though the location and physiography of the two cities differ. Neither is the built form absolutely similar. For instance, Mumbai has a higher number of high-rises than Delhi and a larger area of concrete land, according to the study. But the researchers found that there was not much difference in the two urban area’s land surface temperatures. While Mumbai’s land surface temperature is lower along the coast, its centre, the study found, is “highly heated”.

Apart from a few green stretches in Mumbai such as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park or the mangroves near the Thane creek, the city has a lack of vegetative cover compared to Delhi. Delhi’s large green cover diminishes the effect of the urban heat island, whereas in Mumbai, the study concludes, the “lower vegetation index is responsible for the land surface temperature patterns”.

The Humidity Factor

Many studies, assisted by the availability of satellite data, have looked at land surface temperatures, but this doesn’t take into account air temperature. Partly because air temperature often remains the same throughout the city. But just as there are urban heat islands determined by land surface temperature, scientists also believe that heat islands can be formed due to the atmosphere. This is where climatic conditions of high temperature and humidity, or air’s water vapour content, need to be understood.

In Mumbai, day-time temperatures don’t break all-India records. But for a coastal city, there’s a gap between what it feels like and what the celsius scale shows. This October, Mumbai has been 35 degrees hot which is considered manageable when compared to other Indian cities. But inland places don’t roil under heavy humidity like Mumbai. Mumbai’s current humidity levels are over 60% which is considered oppressive.

“Generally, we don’t consider the role of humidity on heat waves as mostly these happen during the dry season in India,” Dr A K Sahai, scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, says.

As temperatures in coastal cities don’t touch or exceed 40, the condition fails to alarm or coax governments into action. But coastal cities have a different temperature threshold, Rangwala says. “Beyond 35 degrees, the body finds it very difficult to cool down. The combination of humidity and temperature make it overbearing.” The problem is exacerbated by crowding, a common problem across Mumbai’s crammed settlements or public transportation, Rangwala adds.

Increased green cover, vegetation, and water bodies can probably check the intensity of urban heat islands, but there’s an added complexity in coastal cities, according to Dr Sahai. “It can lead to more evapotranspiration which can increase the humidity,” he says. Evapotranspiration is a process through which water is transferred from the land to the atmosphere by evaporation from the soil and other surfaces.

Still, green solutions such as increased tree plantation, rooftop gardening, vertical gardens are the proven top choice. Urban planners have also raised the clamour to use pervious and softer material in buildings and roads construction. The Ahmedabad heat action plan, for instance, suggested a cools-roof programme, which includes false ceilings and roof shingles made of processed clay in slums. Painting building terraces white is also known to prevent the build-up of heat, according to Dr Sahai.

Sensitivity towards heat must become an integral part of urban planning, Rangwala says. “If you allow a glass structure to come at the edge of the road and (if) the developer is not accountable for the heat generated on the road, then it’s a policy problem,” she says. The solutions can’t be city-wide, she adds. They have to be local.

Cities need long-term heat action plans, but they also need immediate solutions. “Better forecasting can be a way of current mitigation,” Dr Sahai says. If a heatwave is forecasted, then (the government can plan around) “stopping daytime outdoors work or allowing parks to open later than the usual time,” he adds.