It all started when a Facebook user Sandhya was browsing multiple online gifting sites for Rakshabandhan this year, and came across a website that sold ‘combo’ gift items for siblings. All that was fine, of course, except that there were some products designed and marketed in a way that specifically addressed one of the siblings as an adopted child, and in a manner that many found to be derogatory.

At a time when the concept of adoption is still not very well accepted in our society, the last thing we need is people making fun of an issue that has so many layers and is such a sensitive one for many. To trivialise it or pass ‘cool’ jokes around adoption, which is often overwhelming for families going through it, is just not done.

As Sandhya delved deeper and did more research, she found that there were a number ofother websites which had similar products and she took it upon her to bring it to the attention of these sites, pointing out that they were actually hurting the sentiments of adoptive parents.

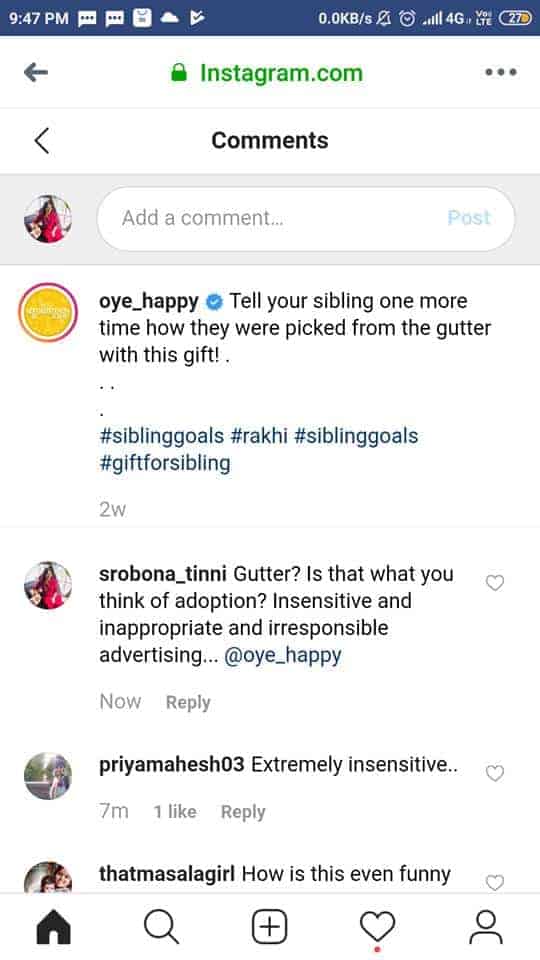

One of the companies indulging in selling such products was OyeHappy. The products listed ranged from magnets, picture stands, mugs and rakhis. Each one of them carried a text where one of the children was a natural sibling and the other an ‘adopted’ one — the latter, mostly represented by a caricature that looked subdued.

[Click on images for larger view]

Sandhya and many others are part of a Facebook group which addresses and discusses the issues, concerns and life of adoptive parents. She brought this to the attention of the Facebook group which joined together to pull such product listings off the website.

In most cases, the companies agreed to pull it down, but some did not. OyeHappy co-Founder replied back to one parent, apologising for the misguided messaging. Other companies like propshop24 and tipsyfly removed the products from their listings as soon as the complaint was raised.

[Click on images for larger view]

On the other hand companies such as etasaa refused to acknowledge the issue and continued posting the same advertisements on their Instagram stories.

Another media outlet, Dice Media published a short skit around a brother-sister relationship. Four minutes into the video and out of nowhere in the ongoing conversation, the brother callously slips in the ‘alienation-by-adoption’ dialogue which the sister jokingly accepts, making it sound like a normal discussion. I went through the YouTube comments and many viewers agreed that it was just a normal discussion.

Which brings us to the question of normalisation: I remember in the 90s there were many songs in mainstream movies that objectified women and contained lyrics that could simply not be passed off as a song today. In fact, such songs would be called out today and all concerned with its production would be at the centre of outrage on social media channels. Is adoption going through the same cycle? Do we need to wait another 30 years to realise this is not normal?

But why is this such a delicate issue in the first place, and why do we need to be more particular about how we look at this?

Let us first understand the set up of institutions in India that facilitate Child adoption.

The Government of India, under the Ministry of Women and Child Development set up a Central Adoption Resource Agency or CARA in June 1990 to regulate, monitor and promote adoption of orphaned, abandoned or surrendered children, with the principal aim of finding loving families for children in need of care and protection.

Then there are State Adoption Resource Agencies (SARAs) set up to recognise and recommend one or more Child Care Institutions (CCI) as Specialised Adoption Agencies (SAA) in each district. At present, there are both government run and non-government run agencies recognised by their respective States to place children in adoption.

Despite such institutions, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) says that India has 29.6 million orphaned and abandoned children and only a fraction of them get family care as adoption rates in India are abysmally low. A study by the Ministry of Women and Child Development shows that out of the 9589 mapped CCIs in India, only 3.5% are Specialised Adoption Centres. This means the number of children available for adoption via the legal channel is alarmingly low.

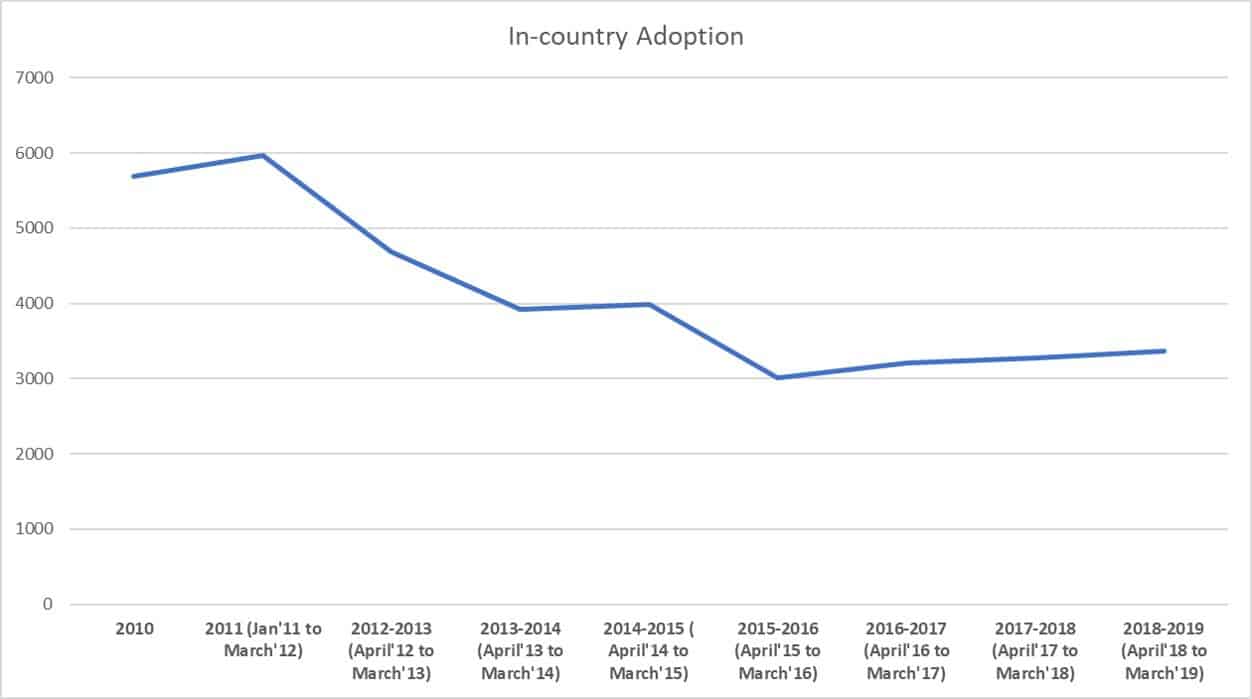

Adoption statistics released by CARA tell us that since 2011, there’s been a considerable drop in the number of children adopted. Given this background, it becomes all the more important to create awareness and sensitise people to look at adoption not as a stigma but as an alternative and fulfilling way to parenthood. Of late, however, we notice that the mainstream projection of adoption has been trivialised to such an extent that it has become an easy tool for commodification.

One thing we need to realise is that it is not easy for either the child or the parent to make adoption work. Children of various age groups face separation anxiety and take time to come to terms with their new family. Growing up, they often face identity challenges as adoptive parents may have little or no information about their past and thus, the children struggle to associate themselves with their current family. The least we can do as fellow citizens is show more openness and sensitivity towards the cause, and never make either adoption or those adopted an object of humour, ridicule or sympathy.