As Odisha’s Jaga Mission progressed, the vision expanded from developing slums into liveable habitats with the active participation of the community, to developing the upgraded slums as empowered units of hyperlocal self-governance. The highlights of participatory slum transformation were discussed in the first part of this series. Taking forward the idea of collaborative problem solving, the Mission now sought to put in place systems to institutionalise decentralised participatory governance in the upgraded slum neighbourhoods.

The objective was to transfer the management of neighbourhoods, encompassing the 4 lakh slum households across 115 cities in the state, to the Slum Dwellers Associations (SDAs) or the Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), so that the progress made in the initial phases of the programme could be sustained through community ownership.

A three-pronged strategy

This model of institutionalising decentralised participatory governance under the Jaga Mission has been functionalised through three areas of interventions:

Robust governance framework: The state government sought to strengthen and develop the SDAs/RWAs as a tier of governance, after the union, state, and city governments. This intent was formalised by signing MoUs between the city governments and all the 2,919 SDAs/RWAs. The MoUs also put on record the fact that the government considered the SDAs/RWAs the fourth tier of governance in urban Odisha.

The MoUs laid down that the SDAs have been formed to bridge the gap between city governments and the community, and to function as an extended arm of the local government in governance and the implementation of developmental activities. The SDAs convene every month and constantly monitor development works and grievances.

SOPs/guidelines have been developed to ensure consistency across the state. The SDAs/RWAs have been further mainstreamed into city life and governance by earmarking positions for them in the ward committees, after making necessary amendments to the municipal laws.

Financial empowerment: The SDAs/RWAs have been financially empowered with bank accounts and allocation of funds to support them in performing their functions as the fourth tier of governance.

Municipal laws have been amended to earmark at least 25% of the development budgets of the city governments for slums and upgraded slum neighbourhoods (Adarsh colonies), in proportion to their population in urban areas. Further, the SDAs/RWAs are mandated to receive supervision fees for developmental schemes implemented in the neighbourhoods which they oversee. Initial transfers were made at the outset as the Jaga Mission implementation began.

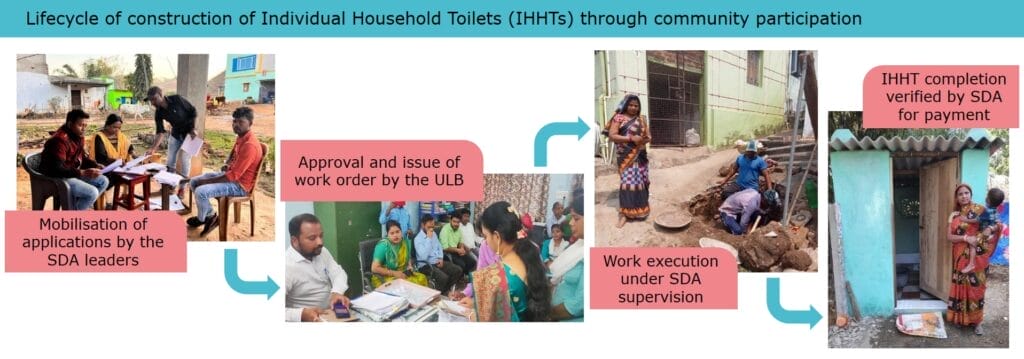

The tasks of the SDAs include supervising developmental activities, monitoring civic services such as water supply, solid waste management, and streetlight maintenance, upkeep of the created community assets, and organising celebrations of national days.

Capacity building: In addition to strengthening governance frameworks and identifying sources of funding for their operations, it was realised that there is a need to build capacity in the system to ensure that the upgraded slum communities are able to sustain and build upon the improvements made. Thus was conceived the Jaga Mission’s capacity building programme.

The programme had two objectives: one, to impart training to office bearers of the Slum Dwellers Associations to perform their roles as the leaders of the fourth tier of governance; and two, to develop a unit to undertake capacity building initiatives of stakeholders for various initiatives under the Mission.

These trainings have equipped over 7,500 SDA/RWA leaders across the state, over half of whom were women, to manage their associations, operate the SDA bank accounts, plan and budget for their communities, prepare for local climate action and disaster management, and so on.

Measures such as these are playing a critical role in consolidating the position of SDAs/RWAs as recognised institutions of decentralised governance at a hyperlocal level.

Read more: How Odisha transformed slums through community engagement

Symbolising people power

The Jaga Mission has shown that the oft-quoted ‘wicked problems’ that our cities face are indeed solvable with the right approach. Empowered SDAs/RWAs are the manifestation of the belief that communities are the right stakeholders to shape and manage their neighbourhoods effectively.

While Indian cities are struggling to manage their affairs due to inadequate devolution of powers and funds, and lack of capacities and enabling frameworks, the Jaga Mission holds immense promise as a model for decentralised governance with engaged communities, thus realising the true sense of democracy — of the people, by the people, and for the people!

The model can be replicated in slums and among other marginalised communities across different states. More importantly, it may be scaled to usher in decentralised governance at the ward level to enable effective localised action in critical areas (such as civic service delivery, maintenance of public health and hygiene, and tackling climate change). This will, beyond doubt, contribute to improved quality of life in India’s cities.