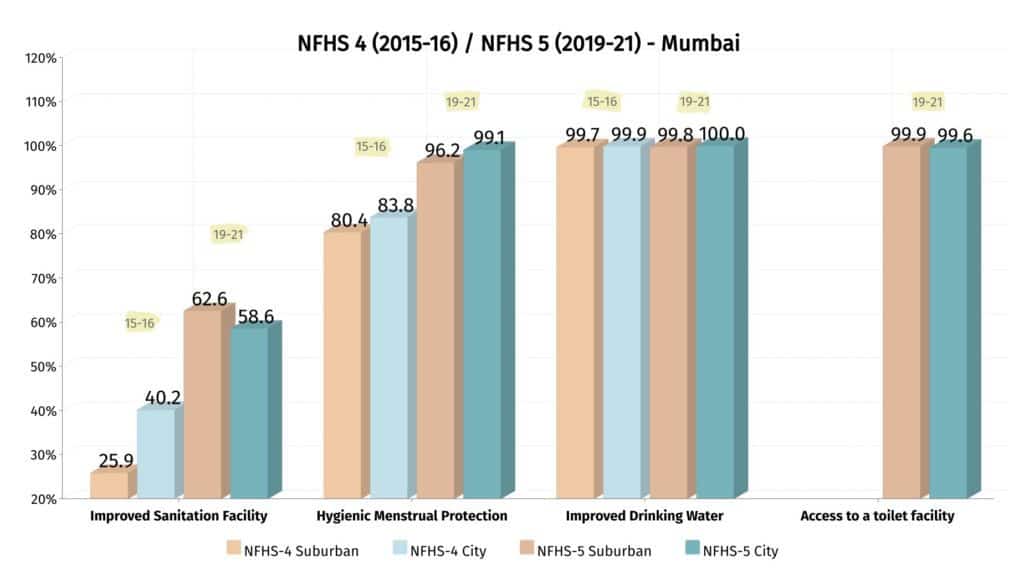

On the face of it, the latest National Family Health Survey 2019-21 (NFHS-5) data appears to tell a straightforward story about sanitation in Mumbai – that of progress. More than 90% of the population now have better sanitation facilities, drinking water access and menstrual protection, according to the survey.

With the exception of 0.01%, nearly everyone (99.99%) gets their drinking water from an ‘improved’ source, which prevents external contamination. The situation did not require a huge leap, as the percentage in the NFHS-4 conducted in 2015-16 stood at 99.8%. Piped water taps (within premises, or in the neighbourhood, or public), tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, tanker trucks, carts with small tanks, bottled water and community RO plants are all considered improved sources.

Strides have also been made in the adoption of hygienic menstrual practices, which include using locally prepared napkins, sanitary napkins, tampons and menstrual cups, among women aged 19 to 24. Previously, the levels were at 80.4% in the suburbs and 83.8% in the city. They have since reached 96.2% and 99.1%.

But when it comes to improved toilet facilities – one that flushes waste away or is a pit latrine, or one with ventilation, composting or a covering – Mumbai still lags. In the suburbs, the population that uses such facilities rose by 36.7%, although at 62.6%, it is still far short of complete coverage. The city fares no better, with use at 58.6%.

Toilets

Despite the significant improvement, 40% of Mumbai continues to use unimproved sanitation facilities. These entail using pit latrines without a lid, dry toilets, and in many cases, defecating in the open.

This number becomes even more striking in contrast to the fact that 99.75% of Mumbai has access ‘on paper’ to an improved toilet facility, but don’t necessarily use it. Only 58% have toilets on their premises according to the 2011 census (including unimproved ones), leaving the rest dependent on public and community toilets.

When asked why this could be the case, Rohini Kadam, team leader of the Right to Pee campaign, points to the poor condition of many public and community toilets. The nonprofit CORO India initiated the campaign in 2011 to advocate for free, clean and safe urinals for women. In 2019, it held funerals for 13 toilets in dire need of repair to call attention to them.

“There is a lot lacking in them. The infrastructure is of such poor quality that water motors stop working and pipes begin to leak in two months since they have been in use,” says Rohini. “The contractors are corrupt, and only do surface level work in all aspects.” Since 2013, these structural flaws have claimed the lives of 16 people, including three children, the majority of whom drowned in underground septic tanks.

Maintenance of toilets built under the Slum Sanitation Project (SSP), a World Bank-funded programme, is the responsibility of a community-based organization (CBO) in each slum. “The basti might not have experience in maintaining a toilet, but they won’t be given any training. Or, the nagar sevak (the corporator) is discriminatory and only allows a particular community to use the toilet,” says Rohini.

A 2020 paper titled ‘More toilet infrastructures do not nullify open defecation’ refers to the political reasons behind it, stating that local leaders prefer low-quality toilets to be built, so they can attract attention for rebuilding them.

Published in the journal of Applied Water Science, the study further analysed data on 8417 public and community toilet blocks, and found that a minimum 71% of all toilets were in bad condition in all wards, with the number going up to 99% in some wards. About Jarimeri in Ward L, the authors write, “The toilet seats are so poor in some places, that people excrete outside the toilet seat.”

Complaints of poor maintenance, lighting, absent or broken doors, intermittent electricity and water supply are common. In the M-East ward, the enclosed spaces become hubs for alcohol consumption, compounding safety issues for women and children.

Read more: People in this Mumbai slum barely make it to 40; here’s why

Scrutinizing access

According to the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), the ideal number of people using a community toilet is 35 males and 25 females respectively. Mumbai fares much worse.

The actual figure per toilet seat ranges between 52 and 100, according to 2019 figures. The situation is significantly worse in the M-East ward, found the NGO Apnalaya, where one toilet seat serves 145 people. Apnalaya’s work focuses on the urban poor in the ward, where 80% live in informal settlements, increasing their dependence on the shared toilets.

Taking suo moto cognizance of this revelation in 2019, the Maharashtra State Human Rights Commission (MSHRC) ordered the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to triple the number of toilets in the ward. Apnalaya was told to be a part of the expert committee to formulate the plan.

“There hasn’t been much progress,” says Raghunandan Hegde, Director of Impact at Apnalaya, three years post the order. “It has never been in the government’s interest to provide them with basic facilities, such as toilets,” he says of the general laxity of the BMC’s presence in the ward, which houses the Deonar dumping ground.

“Because of toilet scarcity, most of the people here either have to stand in the long queue or hold their pressure,” reads the study about Nirankarnagar, an area next to the dumping ground wall. “Many choose to defecate in the open. They make holes in the dumping ground wall and defecate openly on the both sides of the wall.”

Construction of toilets under the SSP has also been sluggish. Only 20% of the 22,770 target had been completed till September 2020. Space constraints and the pandemic were stated as reasons, despite which, an additional 20,000 were planned for 2021. However, the plan was scrapped in November 2021, with only 56% of the initial targets reached.

Water

Data indicating access to an improved source of drinking water is near absolute for the whole of Mumbai, reaching 99.8% in the suburbs and 100% in the city. But these utopian numbers make no differentiation between the type of source providing access.

“When looking at access to drinking water, the numbers may be quite high, but how access is obtained is really the question,” says Raghunandan. “In the case of M-East ward, access existed but came at a very high cost.”

Apnalaya’s work of empowering citizens has made a difference over the years, evidenced in a report titled ‘Revisiting the Margins’ comparing the 2015 and 2020 scenarios in areas spanning nearly half the ward of Shivajinagar. A majority of households now spend Rs 10-19 on drinking water daily, where previously 45% spent Rs 30 and above.

The change is due mainly to the 50% reduction in reliance on tanker and vendor-provided water. Piped water, the cheapest, is now the dominant source for the neighbourhood. However, the consumption of bottled water increased from 0.6% to 5%. Public standpipes account for 30%.

The impact

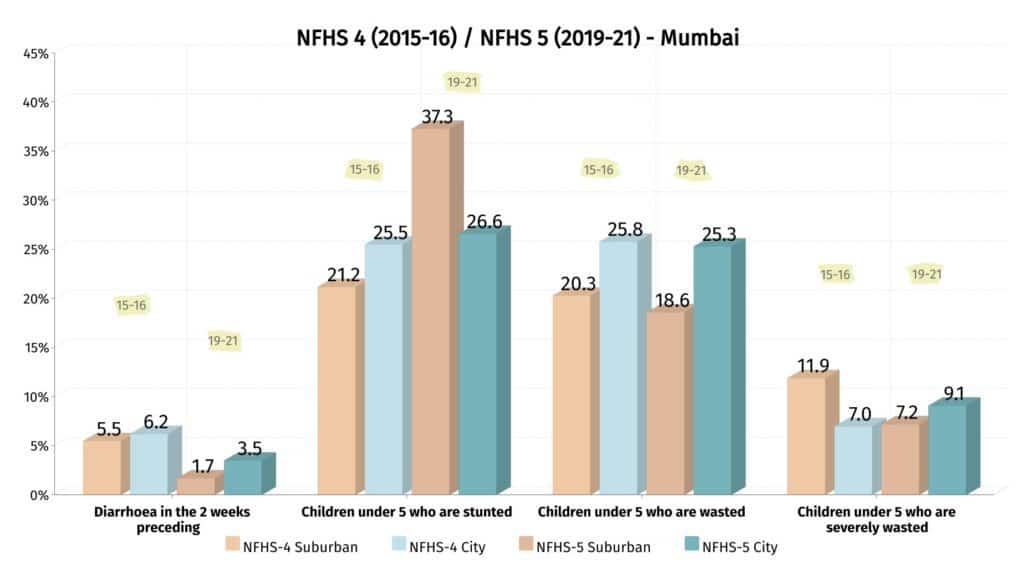

The adverse effects of poor water, sanitation and hygiene vary, but are most severe in children, especially due to open defecation. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates half of all child malnutrition is caused by “repeated diarrhoea or intestinal nematode infections as a result of unsafe water, inadequate sanitation or insufficient hygiene.” The mental and physical harm is often irreversible.

“Children, in particular, have a sense of shame around using community toilets. So to avoid using them, they don’t drink water too frequently, or they hold it in. And that causes a whole lot of health issues,” says Raghu.

So what does the NFHS-5 data say on the health of children under the age of 5?

The prevalence of diarrhoea in the two weeks prior to the survey slipped to 1.7% from 5.5% in the suburbs and 3.5% from 6.2% in the city. Deaths caused by diarrhoea (in those upto age nine) went from 83 in 2016 to 50 in 2019, according to NGO Praja’s State of Health reports.

But markers of malnutrition in some cases point to worse conditions. Cases of stunting in children under 5 (where one is too short for one’s age) have risen. A major increase is seen in the suburbs, from 21.3% to 37.2%, and a marginal one in the city, from 25.5% to 26.6%. The incidence of severe wasting in the age group (those at dangerously low weights) increased to 9.1% in the city and decreased to 7.2% in the suburbs.

“Investment in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) is considered to be the most cost-effective intervention to combat stunting,” writes Payal Seth, a consultant at Tata-Cornell Institute and research scholar at Bennett University. However, research is still in the early stages and not conclusive enough to measure the extent of the link between sanitation and malnutrition in the city.