Recently, a plethora of articles have flooded in both digital and print media regarding a downward spiral in the BEST bus fleet size. The numbers have fallen from 3749 in 2016 to 2959 at the end of last year. While the attention this issue receives is certainly warranted, let’s not overlook the broader transportation landscape of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR).

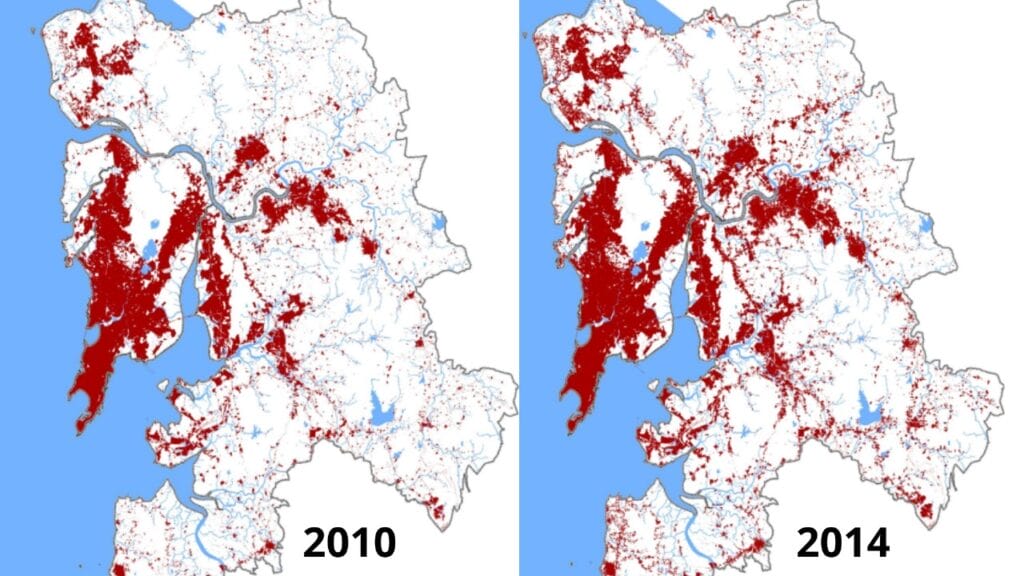

The MMR spans an area of 6328 km², which is 14 times larger than Mumbai which falls under BMC limits (also known as Greater Mumbai). It comprises 18 urban local bodies and over a thousand villages forming a contiguous labour market around the Greater Mumbai core. Yet there is little coverage on the challenges faced by commuters outside of the BMC limits and thus outside of the BEST bus operations.

Some of the key locales include Thane, Vasai, Virar, Navi Mumbai, Bhiwandi, Kalyan, Dombivli, Badlapur, Panvel, Pen, and Alibaug. According to MMRDA’s own study, the population in the rest of MMR already eclipsed that of the Greater Mumbai region in 2021, and by 2026, it is projected to be 13% larger than Greater Mumbai. Buses that operate in these areas operate under separate authorities such as NMMT, TMT, KDMT. Many face issues of overcrowding and low connectivity.

Read more: The gaps in public transport that are pushing people towards private vehicles

It’s time to broaden our perspective and examine the state of buses across the entire MMR to gain a more holistic understanding of the challenges bus systems face in Mumbai, since the city has grown far beyond the arbitrary Greater Mumbai boundaries.

Shrinking fleet and rising populations

According to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority’s (MMRDA) Comprehensive Transport Survey, the entirety of MMR had a total of 7,103 buses in 2016. Although this may seem substantial, let’s put it into context. Consider the number of buses in Greater London: 9300. Despite Greater London having a population of just 88 lakh, compared to MMR’s 235 lakh which is 2.67 times larger! It’s clear that our bus infrastructure falls short in comparison.

What’s even more alarming is the decline in the combined fleet sizes of the buses operated by the big four, for which data is available – BEST, TMT, NMMT, and KDMT – which dropped from 4,789 in 2016 to 3911 in 2023. The fleet size is dropping, as our population continues to grow.

To make matters more complicated, municipalities such as Bhiwandi-Nizampur and areas along the Ulhasnagar-Badlapur belt, with populations exceeding seven lakh, do not have a dedicated bus transport corporation. Many residents in these areas rely on neighbouring municipalities or the MSRTC for transport services, exacerbating overcrowding and over-reliance on suburban rail. Many also have to rely on relatively expensive para-transit modes such as rickshaws and cabs.

Currently, many people commuting to workplaces in Navi Mumbai from neighbourhoods like Dombivli, Ambernath, and Badlapur make a circuitous train journey via the severely congested Thane station. They endure the infamous “super dense crush load” conditions on the suburban rail, even though the road distance is much shorter.

Yet, the bus system along the route cannot meet the existing demand. Similarly people make the journey from Virar to Kalyan-Dombivli via the infrequent Diva-Vasai rail line.

As buses become increasingly overcrowded, commuters endure long queues at bus stops, often leading to disputes. The overcrowded environment poses safety concerns too, with instances of unwanted touching being distressingly common for women, one of the key reasons why a close friend of mine ditched taking the bus altogether even though it costs half as much. Does she not deserve a dignified and safe travel on our public transport system?

It’s not that a large ridership always means poor conditions, take the example of London’s bus network, which transports a staggering 45.7 lakh people every day, surpassing even the London Underground metro system in ridership. This figure is also higher than the ridership of all the bus corporations in MMR combined. Yet, London’s buses aren’t particularly known for terrible overcrowding. This demonstrates the immense potential of buses in addressing our city’s transportation needs.

The problem of overcrowding can be addressed by simply adding more bus services across the region to fill these gaps and these won’t even require heavy investment or land acquisition costs unlike rail expansion or the metro.

Read more: Report card: How charged up are electric buses in Indian cities?

Consolidating bus services under a common entity

To propel Mumbai towards becoming a world-class city, we urgently need to overhaul our bus system on the Metropolitan scale. The current fragmented system, with multiple bus operators running disjointed services, severely limits interconnectivity across the region. The MMRDA could facilitate the amalgamation of all bus transport corporations in the MMR into a unified entity, under a single metropolitan bus agency. Such consolidation would streamline operations and ensure seamless travel experiences for commuters.

Today, while I can effortlessly traverse all existing metro lines using the NCMC (National Common Mobility Card) card and avail myself of hassle-free ticketing with BEST in Greater Mumbai, other bus systems lag behind in adopting this simple technology. The inconsistency extends to bus stop designs, with marked discrepancies in quality between different corporations.

For instance, TMT provides sturdy stainless steel bus stops with an efficient queue management design at many major stops, whereas KDMT has a one-size-fits-all approach to bus stops with a holding capacity of just 15, inadvertently leading to quarrels over whether the queue was broken while boarding a bus. By standardising ticketing systems and services across MMR, we can eliminate these disparities and offer commuters a consistent, reliable experience.

A unified bus operator could also optimise route planning and leverage economies of scale to reduce costs. Consolidating operations under a single entity can eliminate route redundancies and streamline maintenance, ensuring more efficient and cost-effective services. Currently, both KDMT and NMMT operate similar routes between Kalyan-Dombivli and Navi Mumbai, leading to unnecessary duplication of services and administrative functions. Moreover, centralizing accountability within a single organization can simplify communication processes for the news media, facilitating better oversight over historically neglected regions.

Cutting costs and streamlining travel

Establishing a single large bus operator would offer numerous other advantages, including greater bargaining power for procuring buses at lower costs. Surprisingly, the cost for radically expanding the fleet size is not exorbitant even at existing prices. Consider BEST’s recent acquisition of 2100 single-decker AC Electric buses for 3,675 crore.

To match London’s benchmark of 105 buses per 1 lakh population, MMR would require 25,000 buses, amounting to an estimated cost of roughly 45,000 crore rupees. Which might seem like a lot, but let’s put it into perspective.

In November last year, a staggering 63,000 crore rupee Virar-Versova sea link project received approval. Interestingly, two-wheelers won’t be permitted on the sea link, rendering it accessible to only a fraction of the people, who are already a small subset of the population of MMR who reside along the belt. This project also poses significant environmental concerns, from depleting fish catchments to mangrove destruction, all to accommodate a select few. Meanwhile, the MMRDA bemoans its financial constraints when it comes to investing in public transport.

Within public transport too, the more expensive and time-consuming projects such as metro lines tend to receive more attention and investment, often due to their perceived modernity. However, when it comes to scalability, deployment speed and accessibility for the working classes, nothing beats the humble bus system. It’s a shame that we don’t invest more in them.

Read more: Privatisation of public transport: The risks ahead

The MMRDA can and should ensure adequate capital for expanding the bus fleet, securing land for depots, and constructing essential charging, refuelling, and maintenance infrastructure that these would require. Standardising bus signage from Alibaug to Palghar and Karjat to Colaba, along with ubiquitous acceptance of NCMC cards for ticketing, would further enhance the commuter experience.

Furthermore, a single app could be introduced to plan commuter journeys, track buses in real-time, and navigate anywhere across the expansive 6238 km2 expanse of MMR with ease.

Better buses can reduce private vehicle uptake

Once we have a decent number of buses on the road, we can also consider reserving bus lanes on all major trunk roads to ensure that these buses do not get stuck in the traffic caused by the addition of approximately 1600 private vehicles every day.

By offering high-quality public transport with seamless interchanges and reliability, we can curb the growth of these private vehicles on the roads. Consequently, we can address the ongoing decline in average road speeds and rising pollution levels observed across the MMR today.

At the end of the day, if we are serious about uplifting the quality of life of the citizens of Mumbai and abiding by our climate goals, the cheapest and the quickest way to achieve those goals is to build a robust bus system across the metropolis. It can complement the larger metro network, which we are already slowly creating and take significant load off of the overburdened suburban rail system.

By prioritising investment in public transport infrastructure, we can address the pressing mobility needs of our city, while also promoting environmental sustainability and social equity.

| Are you a resident of MMR? Do you spend a lot of time and energy getting to work and back? Do you commute on any route, which you think can be made much better, if there was a better bus service? Do share your experiences and thoughts with us at mumbai@citizenmatters.in. |