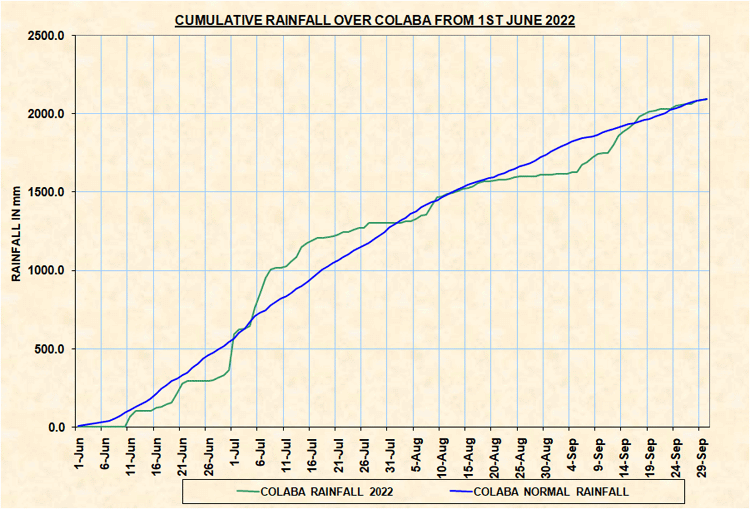

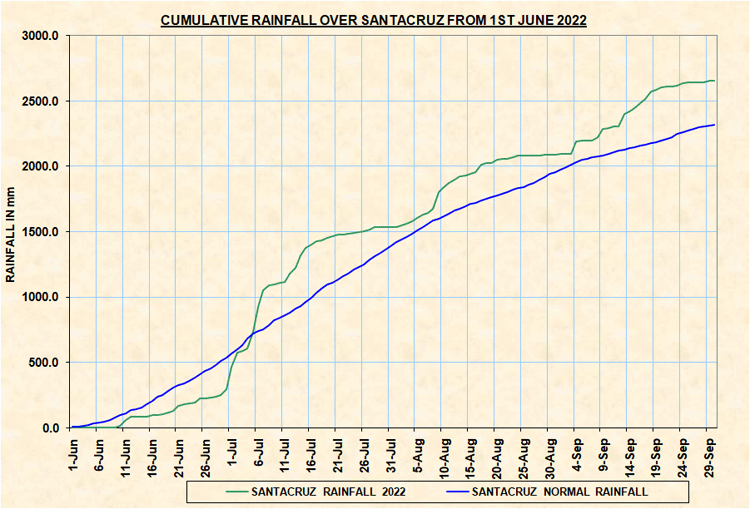

The monsoon in Mumbai is nearing its end, and it’s time to take stock of the season. The rainfall received in the city has just about crossed the expected average, at 101.45% in Colaba, and 106.26% in Santacruz.

The seasonal rainfall received by the city – between June and September – was 2,093.8 mm in Colaba and 2,658.3 mm in Santacruz. The seasonal average normal of Mumbai is 2,317 mm.

But the rain did not stop there; October witnessed more rainfall in 24 hours than the 89 mm expected of it in the whole month. Till October 16th, the rain recorded in Colaba increased to 2,272.4 mm, while Santacruz reached 2,874.4 mm.

But by most counts, says Sushma Nair, a scientist at the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), “There has been nothing unusual about this monsoon.”

The pattern

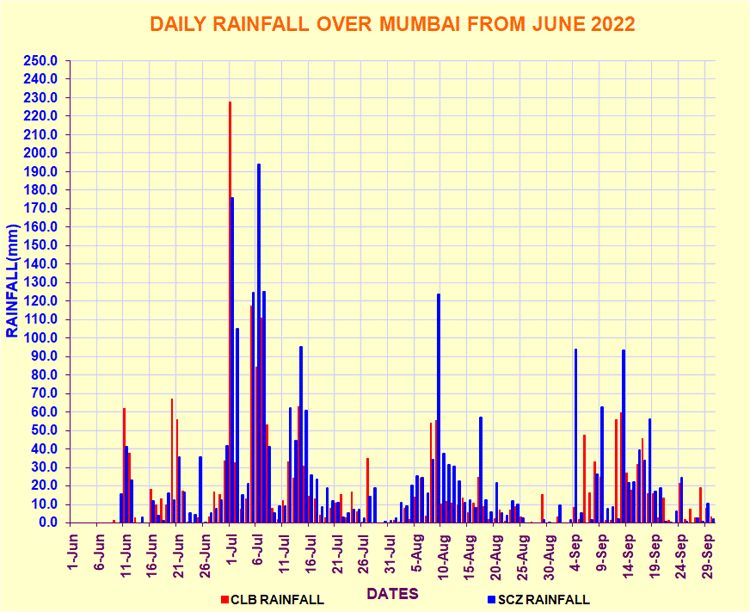

An established effect of climate change on the monsoon is the increase in extreme rainfall events and a decrease in moderate rainfall days over the season; leading to monsoons with short bursts of intense rainfall and long periods of dry spells. Breaking the trend of the past few years, the current monsoon saw relatively fewer heavy rainfall days.

“There is a lot of inter-annual variability in monsoon,” says Sushma, referring to the differences in monsoon – the onset, amount of rainfall and withdrawal date – from year to year. The changes due to climate change occur over long periods. “You cannot attribute a single monsoon to climate change,” she adds.

Instead, other direct and large-scale factors dominated the monsoon in Mumbai this year. One of them is the La Niña effect, a climate pattern that often brings the country good rainfall. The effect was present all season but at a reduced strength than last year.

A late retreat

As the monsoon in Mumbai has been slowly inching towards a retreat, it has been compared by social media users to a guest who has overstayed their welcome. It arrived on June 11th, but according to Sushma, conditions for retreat are expected to be favourable only after October 19th or 20th. The normal date for the retreat is October 8th. Some variation is expected, according to Sushma. Monsoon withdrew on October 14th in 2021.

“The Indian monsoon starts retreating from Rajasthan, marked by a change in the monsoon pattern and large-scale dryness. Retreats in further parts of the country are then declared based on the rainfall,” she says.

| Rainfall in Colaba (in millimetres) | Rainfall in Santacruz (in millimetres) | |

| June | 589.2 | 467.3 |

| July | 715 | 1,071.8 |

| August | 311.3 | 558.7 |

| September | 520.3 | 560.5 |

| Till October 16th | 136.6 | 216.1 |

| Total | 2,272.4 | 2,874.4 |

The share of rainfall in Mumbai in 2022 split by month. Data: AWS

| Heavy (64.5 – 115.5 mm) | Very heavy (115.6 – 204.4 mm) | Extremely heavy (> 204.5 mm) | |

| 2022 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Average | 6 | 5 | 4 |

Compared to the average of years past, Mumbai saw fewer heavy rainfall days in 2022. Data: IMD and the MCAP’s Vulnerability Assessment

The possibility of a water cut

The effects of monsoon last far longer than the season’s duration. The rainfall received has a direct bearing on the water supply to Mumbai for the rest of the year. As of October 16th, the stock in the lakes that supply water to Mumbai was at 14,02,326 million litres (ML), or 96.89% full.

“There is no worry about the water supply,” assures Prabhakar Shinde, deputy hydraulic engineer in the BMC’s hydraulic engineering department. “Though the season is over, it’s still raining in the catchment areas and the lakes are filling up.”

Mumbai gets its water supply from seven lakes, namely, the Upper Vaitarna, Modak Sagar, Tansa, Middle Vaitarna, Bhatsa, Vihar, and Tulsi. The Bhatsa dam in Thane, a major source supplying 55% of Mumbai’s water, is 99.16% full. Vihar lake, in particular, is 100% full.

Read more: Climate change, rainfall patterns and what it means for Mumbai’s monsoon

These conditions mean the chance of Mumbai suffering through water cuts before the start of the next monsoon is thin. “Water cuts are imposed depending on the levels in the lakes at the time and if the onset of monsoon is delayed,” says Prabhakar.

This time last year, the stock in the lakes was 98.9% full. Interestingly, the Andheri, Lokhandwala and Oshiwara Citizens Association noted the rate of filling was a lot quicker this year. By July 17th, the stock in the lakes crossed 8% but had only reached 18% in 2021 and 26% in 2020. This, according to Prabhakar, is owing to the intensity and pattern of the rain.

| Lake | Capacity (in million litres) | Useful content (in million litres) | Percentage of useful content |

| Upper Vaitarna | 2,27,047 | 2,26,565 | 99.79 |

| Modak Sagar | 1,28,925 | 1,05,117 | 81.53 |

| Tansa | 1,45,080 | 1,43,416 | 98.85 |

| Middle Vaitarna | 1,93,530 | 1,80,525 | 93.28 |

| Bhatsa | 7,17,037 | 7,11,001 | 99.16 |

| Vihar | 27,698 | 27,698 | 100.00 |

| Tulsi | 8,046 | 8,002 | 99.45 |

| Total | 14,47,363 | 14,02,326 | 96.89 |

The amount of water in the lakes supplying water to Mumbai, as of October 16th. Data: Hydraulic Engineer’s Department, BMC

Chronic waterlogging

Before the start of the season, the BMC declared an end to a persistent problem the city faces in the city every year: the annual flooding in low-lying areas such as Hindmata, Parel and Gandhi Market, and Matunga. It claimed so due to underground water tanks – below Pramod Mahajan Park in Dadar and under St Xavier’s ground in Parel.

Expansion of the tank at St Xavier’s ground is complete, said an official from the BMC’s stormwater drain (SWD) department, while Phase 2 of the work at Pramod Mahajan Park is still ongoing. The combined capacity of the tanks will be 4.5 crore litres, capable of holding rainwater for three hours.

“There has been quite a relief due to the holding ponds,” said the official. “As and when excess water collects, we dewater it into the holding pond. At Gandhi Market, we let the collected water out into a nullah.”

The result on the ground has been mixed. “There has been some difference, especially in medium to heavy rains, where water logging has reduced to almost negligible,” said a resident of the Hindmata area. “However, in case of very heavy rains, the system is ineffective. The tanks have a limit to their capacity.”

Other low-lying areas prone to waterlogging were fitted with water pumps that could manually drain out the collected rainwater into a nearby nullah or stormwater drain. However, complaints and reports of flooding appeared like clockwork.