This article is part one of a series looking at how the history of building regulations and development has shaped the built environment of Mumbai. Part two will delve into the changes in building regulations over the twentieth century, through suburbanisation, the development plans and liberalisation.

Ask Mumbaikars about the housing problem in the city, and you’re likely to get a different take on the issue from each one. Some will be up in arms about the pervasiveness of slums, which they call ‘encroachments’. Others will point to the absence of affordable housing, laying the blame on either the gaps or excesses in building regulations. Still others will charge the ‘builder-politician nexus’ for running the show behind the scenes.

These problems are hardly new; in fact, they were acknowledged as early as 1860 by the then-municipal commissioner, Arthur Crawford, according to Juned Shaikh’s Outcaste Bombay: City Making and the Politics of the Poor. Slums were a cause for concern even then, although more so due to the health issues they posed. Matchbox-size rooms with netted windows and no bathing space were constructed but had few takers. Industrialists and mill owners, dependent on the cheap and pliable labour of migrants, opposed any significant overhauls to housing and infrastructure.

In the ensuing century, Mumbai has gone through a sea of change. The priorities and incentives of successive governments and administrations have shaped the landscape and built environment of the city, as it has expanded vertically and horizontally. And yet, these problems persist. Some clues as to why perhaps lie in history, according to a new research exhibition in Mumbai.

The plague

The research exhibition and soon-to-be book (de)Coding Mumbai charts the history of building regulations and development in Mumbai. Led by the research arm – called sPare – of the architecture studio sP+a guided by Sameep Padora, it starts with the bubonic plague of 1896.

At the time, Bombay was booming. The city’s new and lucrative cotton and opium trade, land reclamation projects, railways and port trust all demanded labour, which was supplied by an influx of migrants pouring into the city from the countryside. These workers lived in chawls in Byculla, Parel, Tardeo and Worli, constructed on the profits of their labour by the industrials, mill owners and traders.

“The new landlords built commercial properties and private chawls which were often cheaply constructed, cramped and lacking drainage and sewage connections,” writes Dr Shabnum Tejani, a senior lecturer in the history of modern South Asia at SOAS, London.

When the plague hit in 1896, the cramped houses lined closely together proved deadly. “It was evident that poorly constructed and overflowing drains, damp homes, flooded localities and rotting grains in godowns had been responsible for the spread of the epidemic,” writes Marriam Dossal in her article, A Master Plan for the City.

In less than a year, the population halved from a billion, partially due to deaths and people fleeing.

The deaths were not uniform, finds Juned in his book. The death rate among lower castes was tenfold the amount for upper caste Hindus, as the latter were more likely to enjoy better infrastructure, housing and sanitation. “Sanitation and civic amenities became the mode of creating elite and nonelite spaces in the city,” writes Juned, as the administration could no longer neglect the correlation between urban form and transmission of disease.

Read more: Has urban planning in Mumbai failed?

Improvement schemes

This led to the creation of the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) in 1898. “It was given the task of ‘improving’ the city,” writes Dr Shabnum, “by creating new roads and neighbourhoods, clearing slums and providing housing for the working classes. It was to drain swamps, reclaim land from the sea and create new areas for the wealthy classes, as well as prepare for the city’s expansion north.”

The Trust demolished ‘unsanitary’ slums, and in return, built tenement housing in the style of army barracks. It broached the areas of Dadar, Matunga, and Sion. Caste was considered, as those who shared a caste were allotted proximate rooms. One of the chawls built, Dabak chawl, had Ambedkar’s family as residents.

These constructed chawls were, however, not adequate for those displaced by the demolitions. Juned notes that the BIT had evicted 14,613 families by March 1909, but provided only 5,060 rooms as a replacement. Neither were they affordable for the poor and hence were mainly rented out by the middle class. So just as slums in the poorest areas of Nagpada, Mandvi Market, and Chandanvadi were replaced, new slums cropped up beside them.

Street schemes

(de)coding Mumbai also talks about a different kind of scheme undertaken by the BIT: street schemes. These were road widening and organising schemes that aimed to improve standards of light and ventilation. Clearing an east-west path in the midst of congested areas would let the sea breeze through. Organising plots of land with different owners would ensure the area developed so. Dr Shabnum, however, posits that this was done to facilitate an easy commute for the rich, from their businesses in Fort to their new houses in and around Malabar Hills.

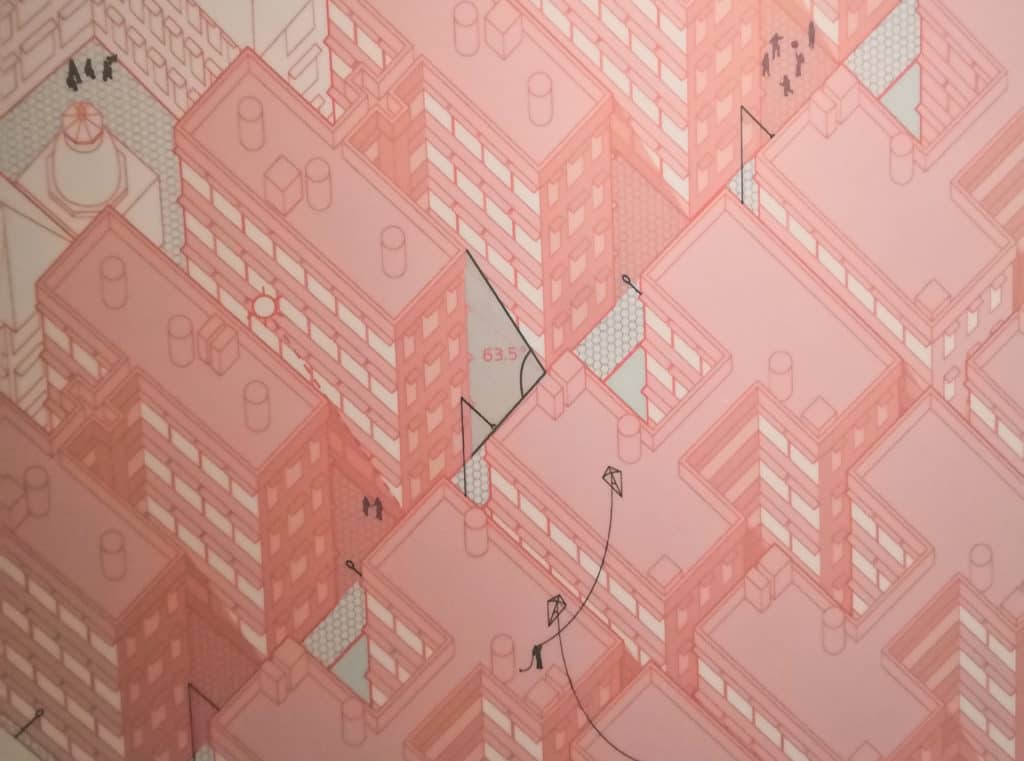

Another of the chief changes in building regulations brought about by the BIT was the “63.5 degree Light and Air Plane Law.”

The law defined the ratio between built-up and open space, although not in the terms we know FSI as today. It defined the maximum angle of incline between the ground and a diagonal line running from the base of a building to the top of the adjacent building. The narrower the space between the buildings, the shorter the buildings would have to be. This ensured that all floors, even the ground, got adequate ventilation and light.

The second half of the 20th century saw a consolidation of pre-existing housing concerns, namely cheap rents and slum clearance. But it differed in form, with the toehold of top-down land-use urban planning in the city. The measures to address them – various laws and regulations – continue to be in force even today – having a lasting impact how Mumbai houses its citizens. More on that to come, in the concluding article of the series.