55% of Mumbai’s population lives in slums, and is routinely excluded from urban planning. Dr Lalitha Kamath, an urban planning expert, has found that it is precisely by design that this structure is created and maintained. The State does not treat all residents of the city equally, and this is just another form of violence. Its instruments are the seemingly technical project and development plans.

Lalitha is an associate professor at the Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai. Her work includes Participolis: Consent and Contention in Neoliberal Urban Governance (2013) and the forthcoming Enduring Harms: Unlikely Comparisons, Slow Violence and the Administration of Urban Injustice.

Below is an edited interview with her.

Violence, to many, means physical or emotional harm. How would you define structural violence, and how does it apply to urban planning?

We see direct violence as an interpersonal and physical event, with victims and perpetrators, that causes pain and suffering.

Structural violence is much more indirect and/or institutionalized, and accumulates over a long time. And instead of a single identifiable agent, a number of individuals and systems contribute to it. Different kinds of structures – cultural, institutional, social, political – are the sites of this violence. The actions that create it are often non-violent – technical or legal – like law or urban planning.

This can result in both explosive and slow violence. The latter happens over many years, and is not always easy to perceive or understand, since it isn’t explicit.

In urban planning, an example of this is the denial of services by the State to particular socio-economic groups. In the buildings of Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) housing, the State permits marginal standards of safety, ventilation, and lighting. There are severe health consequences as a result. A more acute example would be that of mega infrastructure projects, which require eviction and displacement. These are visible instances of violence and are often met with resistance/protest.

Urban development is a violent process, and by conceptualizing structural violence, we can make these subtleties more visible and understand which groups have historically been violated.

You write about the need for a perspective shift through the language we use for our cities: from “smart” and “global” to “ordinary.” Why so?

Jennifer Robinson, an academic, coined the term “ordinary cities” as a way to escape the binary between a Western or developed city and a ‘third world’ city, seen as poor and chaotic. The aspiration is always tied to copying another city, which is higher up in the global hierarchy. Mumbai tries to be like Shanghai, without considering the needs of Mumbai.

For example, in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), 2005, cities were under pressure to submit a ‘world-class’ project plan to get a grant from the centre. A circulating set of consultants often copy-pasted ideas between cities, sometimes forgetting to even change names! The damage is immense if these plans are actually applied, because the context and needs are so different.

Mumbai has the second least amount of open space available per person, affordable housing is scarce and garbage washes up on beaches. Has urban planning here failed?

Let me answer that by talking about the two kinds of urban planning generally understood in the Indian context. The argument I’m going to make is that the planning system is set up to fail.

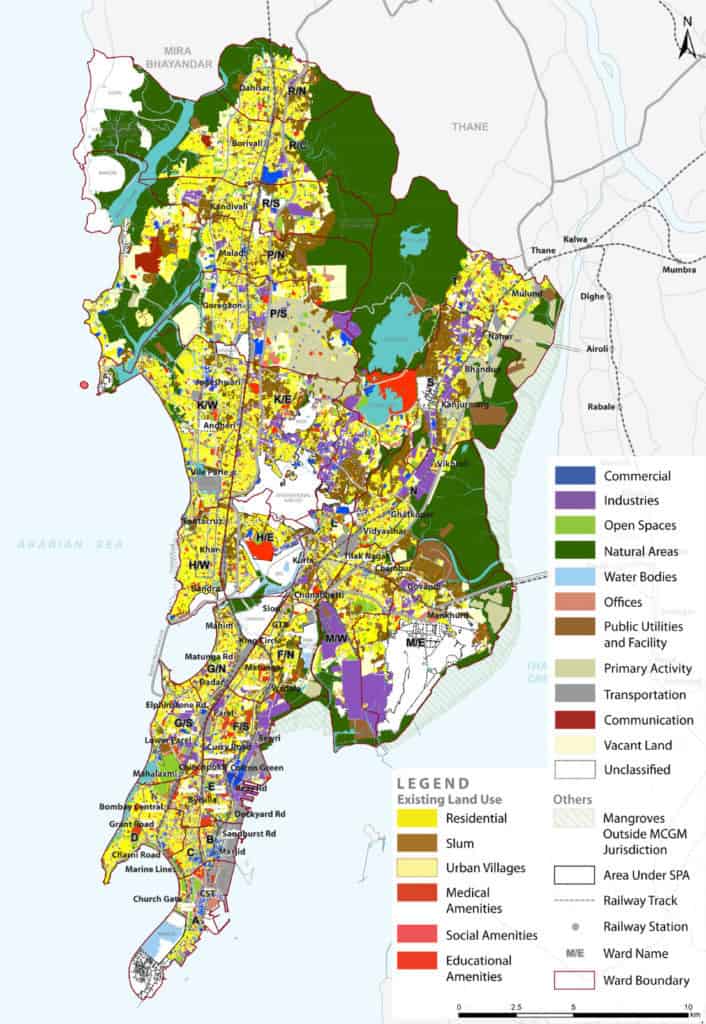

One type of planning is spatial, or land-use planning, which is the development plan. It divides the city into differently coloured zones for enabling different activities, like the yellow residential zones. This way it influences the development potential of different lands.

It criminalizes those that don’t conform to the plan, but legality is subjective. A basti in violation of the DP is occupying land, but a middle class colony created through illegalities, sometimes by the State itself, is not treated with the same contention. A good example of this is Dharavi, which emerged after the poor were expelled from the island city in the 1920s-30s, due to concerns of hygiene and public health. Many of them built informal settlements in the mudflats of the Mithi river. Rapid urbanisation resulted in an influx of waste that authorities could not easily manage, and they started diverting stormwater, often mixed with sewage, into the Mithi river. Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC), in the 1970s, further claimed land from the river, reducing its width, speed and flow. The 2005 floods were largely a result of the Mithi’s choking.

As a response to dealing with the threat of flooding, several bastis were evicted because it was argued they were contributing to the river’s pollution and blockage. At the same time, BKC, whose violations are tolerated, is celebrated for contributing to the world-class image of Mumbai.

The other type of planning is the project plan, which does not consider the larger city, other projects, people or resources. This plan is usually implemented by a special purpose vehicle (SPV) or non-elected government agency, so the potential for citizen involvement or greater transparency is reduced.

Both these types of planning harm poorer groups, and are opposed to the lived cities that we inhabit. Planning was never meant to treat all citizens equally in providing services, land resources, goods, etc.

What is the solution for urban planning woes?

There are many ways to improve planning. The Development Plan (DP) map is very neatly coloured into zones, but far from a reality. Our authorities need to start with what is present in our cities instead of trying to globalize it.

We need to think about planning not just as a technical process, but also a political one. It needs to be opened up to more people, right from the beginning. There is currently no scope, even for collective public consultations, in the Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning Act (MRTP). They only have a limited period for citizens to file suggestions and objections.

Experiential expertise, from fishermen to citizens, need to be central to the making of the plan. That would move the plan away from being solely for property owners to promoting the informal economy – the majority – in the city.

Read more: The story of Mumbai’s Bhendi Bazaar: Redevelopment while conserving heritage

There was extensive participation of marginalised workers in the pre-planning stages of the DP 2034. Did that achieve anything?

For the first time, we saw an opportunity for different groups of people to partake in the planning process, before the draft plan was created. Collectives like the Hamara Shehar Mumbai Abhiyaan used it to expand it in interesting ways. A lot of knowledge was generated. People started thinking about data that better represented their communities, and in fact, rejected and questioned existing planning standards, which they said were irrelevant or inappropriate to their needs. Not all of these efforts, of course, were accepted.

But it was a process of learning, and people actually had the chance to look at the existing and proposed land-use for their wards and compare it with others. In poorer wards, especially along the eastern suburbs, basic services were the central issue, and in the more affluent wards like Bandra, parking was a major point of tension.

Has the Community Participation Law made any difference?

The community participation law was introduced as a condition for the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), for which cities got funds. The law required the formation of neighbourhood level committees to increase citizen involvement at the ward level. But not much has come out of it – many states didn’t implement it or the committees are non-functional.

There is danger in imposing top-down legislation when there is resistance from within different state and city governments. A few corporators I spoke to, not in Mumbai, questioned why citizens should be involved in governance after elections.

Increasingly, what we see is greater centralization in urban governance. More institutions are being created that don’t report to the city government, even though they operate in the city, like the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA). City governments don’t have the power to amend or approve their spatial plans, that is done by the state government.

Policy is important to institutionalise collaboration between communities and the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), but it must be done in a way that communities have significant autonomy to shape and co-lead these processes.

Do the upcoming BMC elections hold any power to affect things?

Election periods are used very strategically by citizens to raise civic concerns, because that’s the time they have high bargaining power. Many things get done before elections, whether it’s laying a road or a community toilet, and many communities will tell you what they managed to get done. These are short-term gains however, and the power to make structural, fundamental changes likely will not come out of city elections alone.

Only a larger movement, with solidarities across different groups, could evoke long-term change.

What role does the middle class play in urban planning in Mumbai? How can they promote inclusive urban planning?

The middle class, one can argue, is complicit in structural inequalities. Beautification processes, that many of the middle classes are in support of, largely contribute to the exclusion of the working class. And it’s because they are the propertied class, the beneficiaries. Supporting inclusion would mean giving up certain privileges and distributing wealth. It’s a political and contested issue.

This is not to say that the middle class cannot be critical. Many citizens have come forward to contest the coastal road project which is endangering the livelihoods of fisherfolk, for instance. It doesn’t happen commonly though.