The unprecedented crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic and the multiple lockdowns has had a debilitating impact on every institution and agency in the city. Wildlife facilities in Chennai are no exception. With tourism being restricted, zoos and other facilities sheltering animals found themselves facing a serious fund crunch to the extent that it became difficult for them to even maintain their regular activities.

Wildlife facilities in Chennai are home to a number of threatened and endangered species too, that require special care. While the institutions maintain that conservation activities have not suffered due to the pandemic, some of them have had to downsize their regular operations to keep themselves afloat. We spoke to people in some of these facilities to get a sense of how they have been managing during these tough times and the kind of support they need.

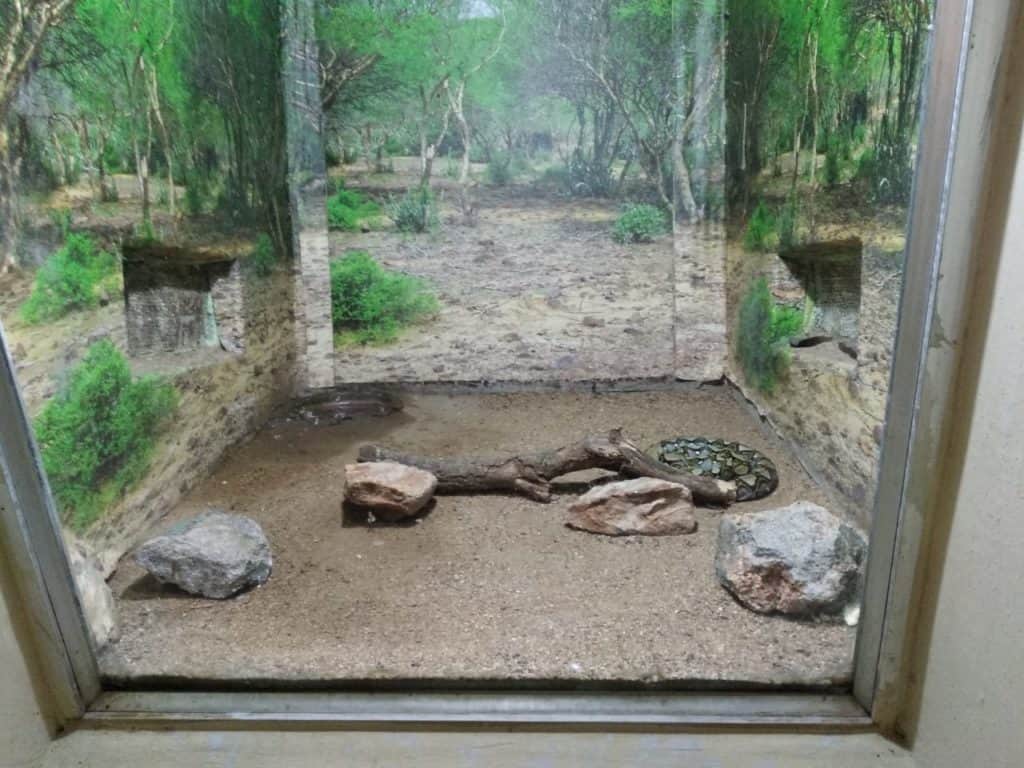

Guindy Snake Park

Spread across an acre, the Snake Park in Guindy, run by the Chennai Snake Park Trust, has 38 species of reptiles including snakes and crocodiles. It is also the first reptile park in India. The park requires Rs 6 lakh per month on average to conduct research, feed animals and carry out regular maintenance.

Ever since lockdown was imposed, the park has been relying on its savings, donations and CSR funds. It also received some support from the Tamil Nadu Environment Department’s Corporate Environment Responsibility (CER) fund. But with these donations nearly exhausted, it has now put out an appeal to the public and companies to extend their support.

The snake park was open to visitors between November 2020 and April 2021, when the state government had relaxed the lockdown rules. “Although our facility was open, footfall was low, as most people had not been vaccinated back then and were worried about venturing out due to fear of infection,” director of the park, R. Rajarathinam, notes.

Read more: Why Chennai’s young bird watchers are much more than just that

The lack of sufficient funds forced authorities to cut employee salaries. There were job losses too. The Snake Park administration employs individuals from the Irula tribe, who are known for their traditional knowledge about snakes and for taking care of the animals. The management halved the number of employees, as they were unable to pay their monthly salaries. “We had 19 workers from the community and have downsized the force to 9 now,” adds Rajarathinam.

The Snake Park is home to endangered species such as Gharial crocodiles, different species of pythons and monitor lizards. The Gharials bred last year during the lockdown and birthed baby muggers, marking an important event in the conservation journey of these animals. But the addition of young ones added to the park’s financial stress, given their special feeding requirements. “They feed only on freshwater fish,” said the trust’s executive chairman, Dr S Paulraj.

Yet another endangered species fostered in the park also requires close attention and care — Reticulated Pythons. Across India, many Reticulated Pythons in captivity die even before they become adults. The absence of conditions similar to their natural habitats makes survival difficult. As a result, many zoos in India have failed to breed these species in captivity. The Guindy park has been able to create a comfortable habitat for them, through years of work. Reticulated Pythons you would see in other zoos in the country are progenies of the snakes bred in the snake park in Chennai.

During the breeding season, the reptiles require extreme care. Dr S R Ganesh, Deputy Director and Scientist at Chennai Snake Park says, “At present, only the mother snake is tending to its clutch. In general, rare and threatened species require a lot of human and financial resources during the breeding season. Although we do not spend directly on the reptiles, our people costs go up as we need more eyes to monitor the reptiles from time to time, make crucial observations and gather data.”

Madras Crocodile Bank

Another wildlife facility in Chennai, the Madras Crocodile Bank in Mahabalipuram, managed by the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, has 15 species of crocodiles, 15 snakes, 10 chelonians (tortoises and turtles) and 5 species of lizards. In all, the bank manages 2000 animals. The expenditure under the main heads adds up to around Rs 25 lakh a month. This covers staff payment, welfare activities, animal conservation and research. The major sources of income constitute visitor ticket income, camps and programmes, and adoptions and donations.

Faced with an acute shortage of funds, the staff members took salary cuts that helped a great deal in the initial months of the pandemic. The bank downsized all expenditure, wherever they could, except the costs connected to animal feed and care.

Explaining how they have been tiding through the pandemic, Zai Whitaker, Managing Trustee, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust/Centre for Herpetology, says, “Since the first whispers about the pandemic and its implications reached us, all of us at the Croc Bank began an intensive funding campaign, reaching out to individuals and organisations in India and abroad. Challenging as this time has been, it has also indicated how much goodwill the Croc Bank has garnered.”

Of the different species of animals, seven are ‘critically endangered’ and need specialized diet and care. “The animals have different requirements at different stages of growth, making their rearing a challenging and time-consuming task. It calls for deep knowledge of reptile biology and husbandry. Nutrient-deficient diets, lack of basking and other activities can lead to serious health issues and diseases in the reptiles,” Zai notes.

The Crocodile Bank has also introduced online events to keep up the general spirit within the facility. The programmes include tours around the facility, conversations with keepers, presentations on snakebite prevention and treatment, and meeting Rom Whitaker, the Snake Man of India and founder of the Croc Bank.

“Research activities have not taken a hit and the adoption programme has done very well during the lockdown; it has also been an opportunity for animal lovers to support us. We are planning more fundraising activities to raise money for the implementation of our master plan, which will make us a truly world-class zoo with unique exhibits and recreation spaces,” Zai mentions.

Read more: What’s that drone over Thane doing during the lockdown? It’s saving forests

Arignar Anna Zoological Park

Located in the suburbs, Vandalur Zoo spends around Rs 80 lakh per month for regular maintenance of animals, premises, research and other regular activities. The major source of revenue is from the state government that manages staff payment and maintenance of the zoo vehicles. Other sources of income include ticketing revenue and income generated by the battery-operated vehicles, leased parking area and food and beverage outlets. This is used towards maintenance of animal enclosures and zoo premises, feed for animals, animal health care and other utilities.

The zoo has 200 casual labourers to take care of the animals and zoo. Although the zoo is partially state-funded, the pandemic has set off ripple effects. In June, the Arignar Anna Zoological Park (AAZP) in Vandalur lost two Asiatic lions to COVID. It is to be noted that Asiatic lions belong to Schedule 1 of Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972 and the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) had initiated a three-year project ‘Asiatic Lion Conservation Project’ in 2018.

Following the detection of coronavirus infection among lions, the Vandalur zoo mandated PPE kits for all staff and spends a huge sum on sanitisation and testing animals.

“Couriering a test sample to the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), National Institute of High-Security Animal Diseases (NIHSAD) and the Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI) alone costs Rs 15000. The standalone cost incurred for sending samples came to around Rs 2,00,000 when we conducted the COVID test for lions,” said Naga Sathish Gidijala, Deputy Director of AAZP.

The zoo is also trying to figure out how to settle other bills, that are usually covered by ticketing and other revenues. “We are buying time from contractors who provide feed for settling the bills. The government supported us by providing Rs 6.5 crore last year. This year, we have requested the government to fund us once more, as visitors are not allowed yet,” Sathish adds.

Read more: Flamingos in the city: Sabarmati project brings winged visitors to Ahmedabad

Future of wildlife facilities

The pandemic has turned the spotlight on the state of wildlife facilities in Chennai. It is essential to ensure that these zoos/wildlife parks can continue to function and also sustain the conservation efforts that go on here.

“The government has the obligatory responsibility to take over the management of all animals across these facilities. However, this would become an additional financial and management burden for the state as well. The state government is finding it difficult, as it is, to manage Vandalur Zoo and Children’s Park due to their closure, so taking on additional financial burden for other facilities may be unfeasible,” states Dr S Paulraj.

Sathish notes that the adoption programme by Vandalur Zoo has received a lukewarm response. In this scheme, the public is encouraged to adopt an animal from the zoo by contributing a sum that goes directly towards the cost of caring for the particular animal.

“We are pushing the adoption scheme, as it can help us manage the animal feed. I feel we can learn from zoos in Karnataka where they have roped in film stars to promote their animal adoption programmes and donation. They received tremendous response,” he adds.

Although the zoo is promoting the schemes in the ways that it can, Sathish feels it could do a lot more to create awareness and increase funding opportunities. “Although the facilities receive funds through CSR initiatives, it is insufficient. We need a lot more companies extending their hands to ensure the survival of zoos and parks,” adds Sathish.

Across the world, many zoos are operated by trusts and facing similar crises. “We have all been looking for support from animal lovers, conservationists and philanthropists across boundaries. Fortunately, there are good people around. There is nothing else to be done, except hope that the menace will depart and visitors will return,” hopes Zai.

Protecting wildlife in Chennai

Those looking to donate/adopt can check the following sites:

- The Madras Crocodile Bank Trust & Centre for Herpetology

- Adopt our Animals Online | Animal Adoptions – Arignar Anna Zoological Park (aazp.in)

- Donate to Snake Park: Chennai Snake Park Trust, A/c no: 10792456546, State Bank of India, Adyar Branch, IFSC Code : SBIN0013361

Can you add links for how we can adopt animals at these facilities? It’s not clear to me how to contribute, some direction would be appreciated.

Hello!

Snake park has a list of requirements for sponsoring animal feed and maintenance. Since their website is down, please check: https://milaap.org/fundraisers/support-snakes-and-reptiles

For Madras Crocodile Bank, the details are displayed on their website. Check here: http://madrascrocodilebank.org/web/make_a_donation

For Vandalur Zoo, check: https://tickets.aazp.in/index.php