With ornately carved arches, Rajasthani-style false balconies and decorative brackets, it is easy to mistake this quaint little building for a mini palace. Cloaked by the flamboyant Gulmohar outside, the Madras Literary Society, a treasure trove of archaic books and venerable first editions from the 16th century patiently waits to share its hidden gems with the curious visitor.

The history of the Madras Literary Society can be traced back to the College of Fort St. George set up by the British East India Company in the early 1800s to help English engineers get accustomed to the vernacular language, practices and customs. Historian and city chronicler S. Muthiah in his book “Madras Rediscovered” speaks of the Madras Literary Society (MLS) as “perhaps the oldest subscription library east of the Suez”.

While the Society was formed in 1817, it moved into its current home in 1906. If the exteriors got you thinking it was a mini Rajput palace, be prepared to hold your breath as you enter: Steep ladders to help navigate through bookshelves that scrape the 60-feet-tall ceiling, pulleys strategically positioned to transport volumes from the upper levels to the ground and light streaming in through double layered windows will make you wonder if you magically got yourself transported to the library at Hogwarts or the Maester’s Citadel in Westeros.

The layered windows ensure that the two-storey high hall remains wonderfully ventilated. Wrought iron rods are used in place of solid iron blocks for platforms holding the shelves in the upper levels to enable light flow. The building is probably the first if not the only one in the city to have been constructed specifically to serve as a library, where readers can enjoy their book without the need for artificial lighting or fans to keep them cool. The architect, however, continues to remain unknown.

The government-owned stately building is maintained by the Public Works Department (PWD) and the MLS has remained a happy tenant all along. Thirupurasundari Sevvel, Honorary General Secretary of the Madras Literary Society, acknowledges the importance of government support. “The library has never been closed, not even once since its establishment. Post-independence, it would not have been possible to keep the space alive had it not been for the PWD’s commitment to keeping this building well-maintained; essentially ensuring that it remained a piece of living heritage without losing its character,” she mentions.

Living heritage

While the architecture intrigues and enraptures the beholder, the building stands for much more than its jharokas and lime-plastered walls.

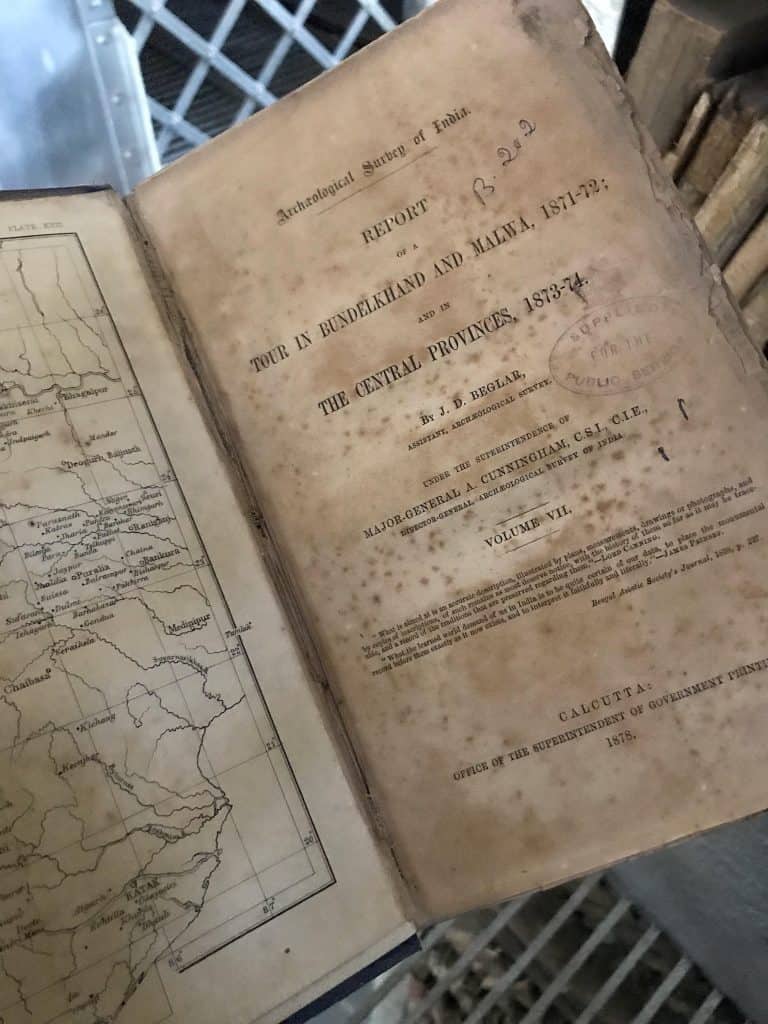

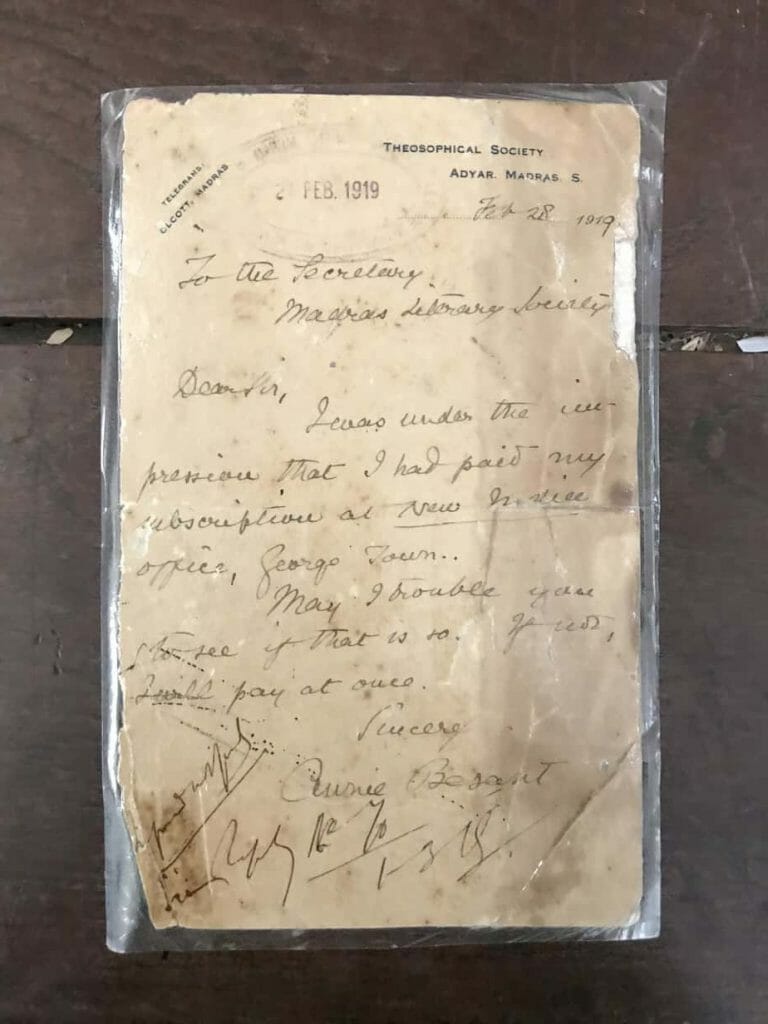

Among the society’s prized possessions are a 17th century publication of Aristotle’s Opera Omnia in Greek and Latin. A first edition copy of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica also sits pretty in their collection. This apart, detailed observations and maps of the Ganges Canal plain dating back to 1854 along with the Buckingham Canal project have been preserved impeccably by the library. The library had, over the years accumulated around 80,000 books, from rare first editions to dissection guides and detailed field maps. Sadly, gaps in cataloguing meant missing books.

In a bid to streamline processes, the MLS’ governing body initiated a slew of reforms at the turn of the millennium–the Dewey Decimal System of classifying books was introduced to improving cataloguing, restoring old books was prioritised and inducting new members was taken up with renewed vigour. “We now have a total of around 50,000 books and no books have gone missing since we started cataloguing using the Dewey Decimal system in July 2000. The MLS library staff, along with a few volunteers, have managed to mark and catalogue close to 18,000 books under the new system so far,” says Thirupurasundari.

One of the library’s most valuable assets is Head Librarian Uma Maheshwari, loved immensely by members and patrons. From providing book suggestions based on interest to enthralling topical discussions, she has been an integral part of the library’s recent history. “Earlier, institutional memberships were high and we used to do home deliveries as well. The trend has since changed with members increasingly preferring to come directly and soak up the library’s warmth,” she adds. Uma also happens to complete 25 years at the service of MLS this August!

From Attending talks to Adopting books

To resurrect books which in terrible shape, the society has come up with the unique “Adopt a book” scheme where interested citizens can pay towards the restoration of a book. Alternatively, one can also dedicate a book to a loved one to commemorate an occasion or adopt a bunch of books as part of a company’s mandatory corporate social responsibility spending. “This scheme has helped us identify and protect old and important books of high literary value from dying a slow death. We acknowledge the contributor by having their name printed on the inner pages of the restored book,” remarks Rajith Nair, Committee Member of the MLS.

For the antiquarian value of books to be preserved, restoration has to be reversible–meaning, the book should be able to get back to its pre-restoration state without evident damage. Keeping this in mind, individual pages are sealed in photo lamination sheets without damaging the book’s collector value. Prior to the sealing, books are thoroughly dusted, pages numbered, de-acidified and fumigated to improve their life. The leaves are then carefully bound using resins to keep pests away. “By doing this, the lifespan of these remarkable editions is increased at least by another 50 to 60 years,” insists Rajith.

Critical shortage of staff and volunteers

While complaints about how dusty the shelves are and how difficult it is to find books are not infrequent, it must be kept in mind that it is only membership fees and donations from patrons that literally keep the library going. With one head librarian and two assistants, the library, it is safe to say, is critically under-staffed. “Volunteers do drop in from time to time to help tag and categorise books. But the amount of work left to be done far outweighs the volunteer or staff strength here,” rues Uma.

Inspired by her son, Janet has been volunteering at the library for a month now. With a column of books stacked in front of her, she’s seen skimming through titles trying to fit them into the various Dewey categories. “I have made it a point to come in at least twice a week and spend around an hour or two here to help with the cataloguing,” she says.

The library is on the look-out for regular volunteers who can come in at least four to five times a months for a few hours to organise and catalogue the books. Once the initial briefing cum training, which happens on Saturdays, is completed, volunteers are free to come in whenever they can during the library’s working hours. They currently have around four to five serious volunteers who come in regularly to help out, and a few college students who come in batches to take up some minimal work.

While entry to the library is restricted only to members, the MLS throws the space open to non-members more often than you’d think. The library is usually abuzz on the second Saturday of every month with talks, performances and book launches organised by private establishments or individuals. Allowing access to the space has by itself acted as a potent catalyst in turning non-members into serious members, helping the cause further.

Keeping this unique piece of Chennai’s collective heritage alive is our collective responsibility. From organising workshops to volunteering or becoming a member to talking about its activities to friends, you can help the MLS out in your own small way. “But, more than anything, just come visit the library and soak in its rich heritage. Let’s start there,” says Thirupurasundari. Word.