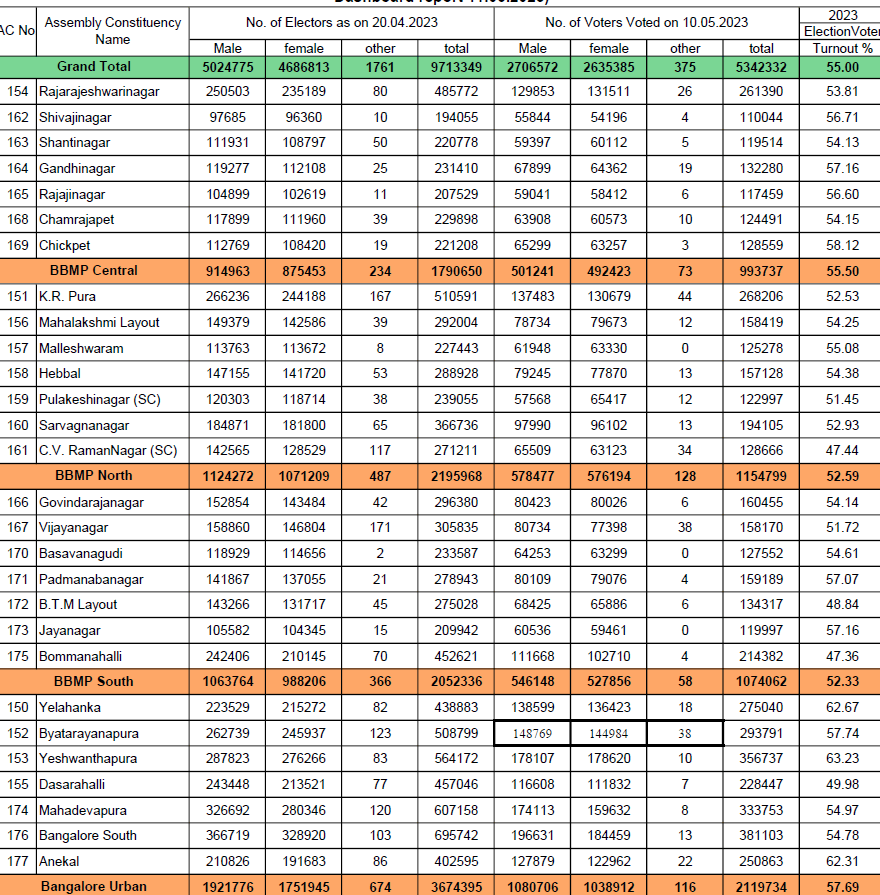

As polling ended on May 10th, it became clear that Bengaluru would have one of the lowest voter turnouts in the state. Election officials estimate that the entire state had a turnout of 73.19%. In Bengaluru however, only around 55% of the registered voters showed up to the polls.

BBMP South recorded 52.80% voter turnout, BBMP Central recorded 55.39%, and BBMP North had 52.88% voter turnout. Bangalore Urban district, which comprises the peripheral constituencies like Yeshwanthpur, Byatarayanapura and Mahadevapura, recorded around 56.98% voter turnout.

As headlines condemning the city’s apathy pour in, some citizen groups feel differently. The poor turnout is a result of apathy for sure, but some citizens believe that lack of inspiring political choices, poor management of electoral rolls, and excessive control by election officials were also to blame.

Always a poor show at the polls

A look at the past voter data suggests that getting Bengaluru to vote in droves is an uphill battle. Voter turnout has declined greatly in the last decade. During the 2013 assembly elections, the city had a 62% voter turnout while in 2018, it was 54.1%. Even in the 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections, voter turnout, in the city, did not cross the 55% mark.

Election Commission of India launched the Systematic Voters’ Education and Electoral Participation programme or SVEEP, whose primary goal was to increase voter turnout across the country. The CEO-Karnataka attempted to use music, dance, ‘vote fests’ and road shows to urge people to register to vote and then show up.

Perhaps their efforts paid off in the rest of the state. The statewide turnout was slightly higher than the 2018 elections. But in Bengaluru that needle did not budge.

Across WhatsApp groups of RWAs and apartment associations in the city, the burning question is why? Why do Bangaloreans not vote?

Urban voter apathy is a widely accepted phenomenon in India. In 2022, the Election Commissioner deemed it a problem across the country. This trend is typically attributed to urban voters being wealthier than their rural counterparts and less dependent on politicians for their everyday life. Even within a city, poorer constituencies turn out in greater numbers than the richer ones.

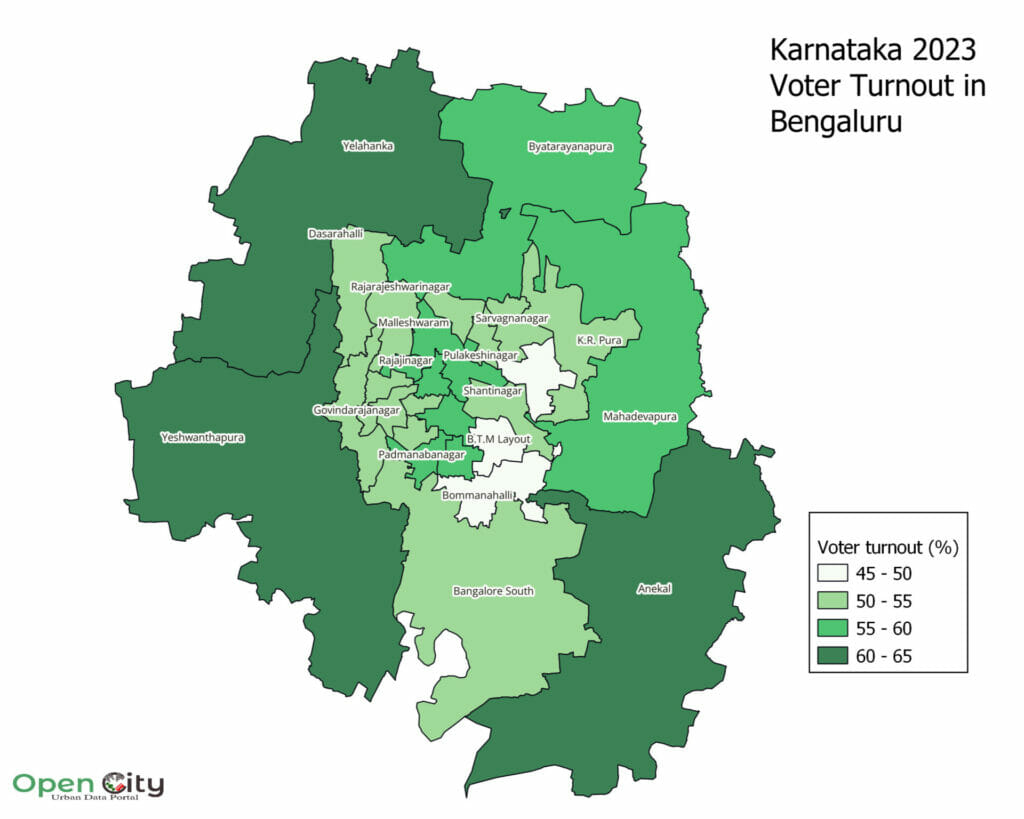

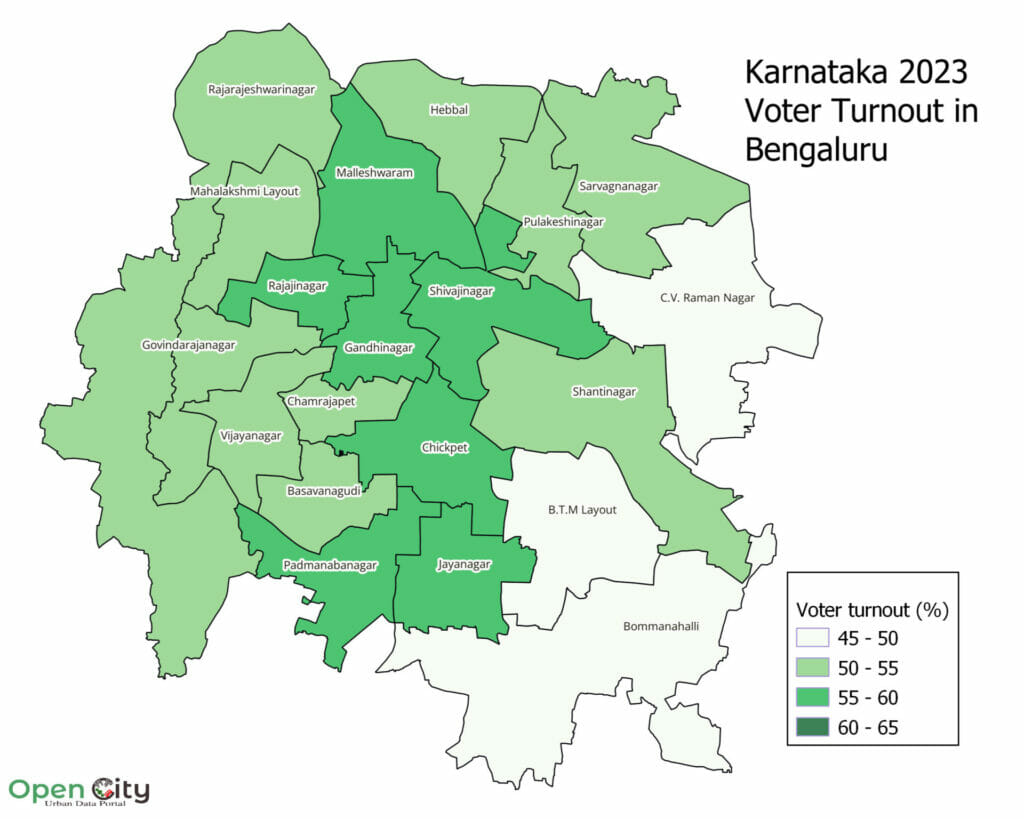

This pattern appears to hold true for some constituencies in the city. Peripheral constituencies like Yeshwanthpur and Yelahanka, which have several gram panchayats and a substantial rural population, had the highest voter turnout in the city at 62.6% and 63.2%, respectively.

However, Byatarayanapura and Mahadevapura, constituencies, with a similar urban-rural profile, did not fare substantially better than urban constituencies like Jayanagar. Constituency wise voter turnout can be seen on the data platform Open City.

Inaccurate voter rolls

Part of the problem, according to many, is the voter roll management. Vikram Rai, general secretary of the Bangalore Apartments’ Federation (BAF) believes that the efficiency of the electoral process needs greater scrutiny. Vikram believes that it is wrong to chalk off a repeatedly low voter (always around 55% he points out) to apathy.

“There is something systemically wrong with the voter base,” he says.

BAF has been closely involved in trying to improve voter registration and turnout on polling day. But there is a reluctance among the city’s large corporate migrant population to register in the city’s constituencies rather than vote in their native towns, Vikram notes.

“This is because the process still feels cumbersome to many, even people who are well settled in the city,” he notes. “While this doesn’t affect voter turnout, it does need to be addressed”, he says.

“Apart from this, there is poor management of voter rolls,” Vikram adds. Wrongful deletions, duplicate entries and bloated voter rolls were adding to the problem, according to him. He cites the case of his own parents who shifted from Bangalore to Udupi. “Their names are still on the voter rolls here,” he says.

Even as far back as 2018, Commander PG Bhat, a voter reforms activist and software engineer, detailed how bloated the voter lists were. Bhat noted that the voter rolls were full of repetitions or fake entries; even if every eligible voter had been enrolled in 2018, there would have still been 13,90,421 unaccounted entries in the voter rolls.

Read more: Final but not foolproof: Errors continue to appear in electoral rolls

Bhat documented the same problem in early December 2022 as the News Minute and Pratidhvani broke the news of the illegal voter data collection and fears of voters being deleted off lists in Shivajinagar constituency.

Lack of political legitimacy

Vikram doesn’t completely rule out apathy, particularly from the middle to upper-middle class section of the city. “They may complain about bad roads or traffic, but their daily life is not affected by politics,” he says.

But he also believes the apathy is because there is little faith that the political candidates presented to voters will solve the city’s complex problems. “Most political candidates also do not appear impressive”, he says.

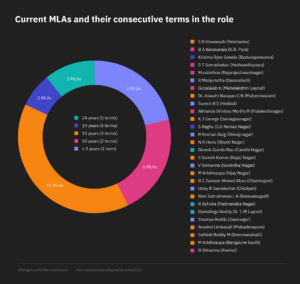

Vikram is also critical of the poor communication and campaigning by most political candidates. “They do not give you a sense of what work they have done or what they plan to do,” he says. Instead, it appears that most legislators in the city simply win seats because of past victories.

According to analysis done by Deep C and Srinivas Alavalli, at least 16 of the city’s 28 MLAs have been in power for 15 years or more. Many of these politicians simply made no effort to woo apartment dwellers, who constitute approximately 20% of the city’s eligible voters. Vikram notes that even apartment complexes with 800+ houses did not see any campaigns from legacy national parties.

Read more: Bengaluru MLAs are long timers: 16 of 28 have been legislators from 2008

“It appears that legacy politicians can simply win by keeping their core base happy,” Vikram muses. “They do not need to win over the remaining voters in the city.”

This issue was made worse by the election officers arbitrary implementing of rules, he points out.

BAF, in a bid to improve voter turnout, decided to organise townhalls with candidates from different constituencies across the city. [Editor’s note: Citizen Matters was the media partner for this endeavour]. The idea was simple: Candidates would present their vision to apartment dwellers across BAF clusters spread out in different constituencies in the city. Residents would also get to ask questions of the candidates.

However, election officials in the city shut it down suggesting that private entities could not hold such meetings with candidates as it violated the Model Code of Conduct. Vikram recalled the Special Commissioner for Elections telling him that the residents should not do anything political.

“It baffles me,” he says laughing. “We are supposed to vote, but not be involved in political process.”

The model Code of Conduct is supposed to apply to political parties and candidates. “Why did they apply this to voters?” Vikram asks. Meanwhile, the ECI has taken little action against political candidates and parties openly violating the model Code of Conduct, by campaigning 48 hours before the election or placing full page advertisements on the day of the election.

This arbitrary application of rules robbed voters of a chance to truly evaluate candidates and ask them questions. “We have candidates with serious criminal charges against them. We could have publicly asked them about these cases,” he points out.

In the same week when election officials refused to allow town halls, they asked apartment associations to conduct music and dance programs encouraging residents to vote.

Vikram asserts that having such a communication channel with candidates would have made the process more meaningful than preaching the virtues of voting. “The secret to improving turnout is to build that political engagement and legitimacy,” he says.

Someone had to tell this. Hats off. Finally someone spoke this !!

I am a typical case of election commission apathy. I shifted to my current residence 10 years back and raised request to change the address to reflect my current address and accordingly new polling location in case of elections. Instead I was given a new voter id with new EPIC number without deleting the older one (Then I raised the request to delete the same via voter portal about 7 years back. No action taken by election commission). This was the case for all 4 voting members of my family. So our name would appear at two places on election site. This time they went a step further and deleted the voter account of our new location where we have been casting our vote for past 10 years now. I raised this issue in April month itself, yet nothing moved (the ticket is still in a submitted state on nvsp.in portal, using the older EPIC number which was never deleted, to now change the address).

We should consider *ONE MORE ASPECT* in the result of the *TURNOUT.*

*THOUGH THE PERCENTAGE OF POLLING HAS NOT RISEN MORE FROM PREVIOUS TIMES, THE QUALITY OF VOTES HAVE CHANGED.*

In previous *ELECTIONS,* that *QUANTUM* was reached which was along with *MALPRACTICES / FORGERIES* votes.

When I shifted and registered for a change of address, they gave me a voter id card with the same number in the new constituency, but it is still registered in the old address/constituency also. They didn’t delete it from the old constituency. In effect my personal voting percentage is 50% :-).

In other constituencies across the state, voters are lured into voting by the political parties giving money before elections. In many cases by multiple parties. So an individual gets up to 10,000 in an election to vote. In Bangalore no one offers anything. Why should you go to vote? Anyways, these politicians do nothing. So the NOTA is the only option for people who are fed up. Why bother going and doing a NOTA vote? This is the outcome.

Voter gets disillusioned by the political parties,post poll alliances makes fun of democracy.