A city that once looked like a picture postcard, with glassy lake and chinars, today seems to have become an extended army camp. Srinagar, the capital of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, conjures up the image of a remote world under siege.

A 11-member fact-finding team of advocates, trade union human activists and a psychiatrist recently released a report titled ‘Imprisoned Resistance’ after a visit to the strife-torn state from September 28th to October 4th. Denying the Centre’s clamorous claims of “normalcy” in the region, the team divulges that the people have reacted with their own hartal. As a resident quoted in the report, says, “Kabhi curfew hain, toh kabhi hartal. We have been trained all these years to adjust to such a situation.”

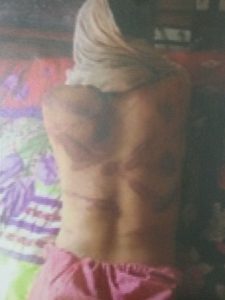

“Abnormalcy is Srinagar’s normalcy today,” says Ramdas Rao, a visiting team-member from the All India People’s Forum. “When you walk down the streets, you find very little to cheer you.” He explains that the shops are shuttered and bunkers, barricades and concertina wires block the roads. At any point in the night, the army just barges in, takes what it wants and tortures the people.” He shows pictures of a 17-year-old who has been shot with pellet guns. “This is the grim situation everywhere.”

Sanjay Kak, film-maker and another team-member who has visited Kashmir four times since 2010 tells us there is an now uneasy peace because of the clampdown on mobility. Protestors are not able to move around much, so the stone-pelting has come down. However, he also senses that there is more fear among commoners now. “The soldiers go there and say, now that Article 370 is gone, we can marry your women.”

Mobility

Most buses have been suspended since August 5th, the day the Centre revoked Article 370 and bifurcated the state into two union territories, at the same time imposing an unprecedented lockdown. Only a few private buses were seen to ply but they charged exorbitantly for tickets. The roadblocks make it impossible to walk through the streets, let alone drive. Wahid*, a resident, retorts that the government probably does not even want the people to know their way from a home to a hospital. “We do not venture out of our homes because we don’t know whether we will return,” he explains.

At heavily barricaded checkpoints, the residents have to show their Aadhaar card, mention their name and village and are frisked, though non-Kashmiris are allowed to pass. One young man says: “Even in our own land we are not allowed to move freely and are required to show our identification to army people from outside.”

Air tickets can only be bought at the Tourist Facilitation Centre, as Internet services have been hit. The railways, meanwhile, from Qazigund to Baramulla, have been totally shut down. “Why have they shut it down? What are they afraid of? Are they afraid of normalcy?” asks Wahid.

Communication

Another citizen Loney* describes how his family got news of the death of a close relative only in the night, although he had died the previous morning. The clampdown on mobile telephony, fixed-line services, Internet and social exchanges have ruled out contacting basic services, such as hospitals, bank services or the fire department.

No new lines have been issued except for high and middle-level government employees. One public prosecutor in the District Court flaunts his phone, but only government officials seem to be whitelisted.

On September 29th, Amit Shah had said that 41,800 persons lost their lives in militancy, so withdrawing mobile connections for a few days is “not a human rights violation”. The committee’s report mentions that the government has said it is willing to install 10,000 BSNL fixed-line phones. Although 6,000 applications have been received from September 4th, very few of them have been installed, depending on the availability of equipment or cables. Fixed lines are available only from the Srinagar Lal Chowk exchange office, but a 75-year-old retiree who somehow managed to hitch rides up to the office was told that there would be no facility for a landline “until he can find 50 new subscribers in his area.”

Essential services

Postal services have also shut doors, except for the General Post Office in Srinagar, which is open till 2 p.m. even though it sells no stamps and letters can be sent by Speed Post alone. The post has not been collected or delivered since August 5th, as the sorting offices are closed. It also ensures that no one can send a notice on any issue. No RTI application can be filed, nor is the government obliged to reply to any.

At the Srinagar main branch of a leading public sector bank, a manager comments that commercial and private transactions have come down to less than 10% of their monetary value. Apart from official salaries, there are not too many government transactions, as construction and development work has grown progressively slower.

Schools and Primary Health Centres (PHCs) are partially or almost totally closed, and occupied since July not by students or teachers, but by the armed forces. The District College in Pulwama is firmly shut, as are all the schools and anganwadis. One disturbed student says that “there is one janaza (funeral prayer meeting) to attend everyday.”

Even government employees are terrified. Latif*, in government service, explains that ironically attendance, especially at the Civil Secretariat, is improving, touching 70% on most days. But the government cannot enforce anything as they have turned off the Internet, so the biometric system is not working. Employees record their attendance in manual registers. Latif mentions that one order asks for lists of employees “known to indulge in political activity or who are members of a political group.”

Trade and commerce

Economic instability looms large, as 11,000 Kashmiri workers in Rangreti Industrial Park just outside Srinagar are now jobless. Niyazi, owner of a start-up, says that all jobs today are dependent on the Internet, which has been disconnected. A carpet exporter comments: “Who shut everything down? Who brought economic life to a standstill? Government of India…”

The fields that have been hit the most include baking, tourism, leather and the apple industry, which has an annual turnover of Rs 10,000 crore. Mandis are fenced off and milling with security personnel. Each local mandi is associated with about 800 companies, but 10,000 laborers find themselves jobless today, with a direct loss of Rs 20 crore per day and indirect losses worth Rs 50 crore per day.

Traders seem to have dug in their heels and refuse to sell apples to the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation (NAFED) at the offer of 50% on the market price. Srinagar’s Paripora Fruit Mandi looks like a ghost town, without even one trader, truck or functioning godown. Muhamed*, a trader, retorted: “Does the Indian government think we are beggars that we will sell our produce to them at a premium?”

In the leather industry, traders sold 300 to 400 hides per day, but today they are burying the lot! The vibrant tourist industry is now in the shade, as the government ordered tourists to leave. About 50,000 tourist taxis, 1,000 houseboats, 1,500 hotels and 650 shikharas are stagnating.

Newspapers have discharged reporters they could not pay. Most of their work is now dependent on “pen drive” journalism, merely dishing out information given by the government. The independence of the local judiciary too is scorned, especially on issues involving the armed forces, mainly due to a lack of urgency in either the habeas corpus matters of the High Court or the blockade and restrictions in the Supreme Court.

Ultimately, the city looks like an army barrack, but there is no clarity about the way forward. As Sanjay Kak puts it, “The government refuses to divulge information and plays with its cards close to its chest.”

There is only the feel of fear about the present and a smell of doubt about tomorrow.

[*Fictitious names have been added to the people who spoke to the team and have been quoted in the report.]