[Part one and two of this series traced the history of Kannada signage rules in Bengaluru and the history of the Kannada movement, respectively. Part three looks at what the government is doing to promote Kannada]

Rupa migrated to Bengaluru from Jharkhand a year ago. She works at a petrol station in North Bengaluru. She doesn’t speak much Kannada, though she can manage a few words. She is trying to learn Kannada by talking to locals around her, but it is not easy.

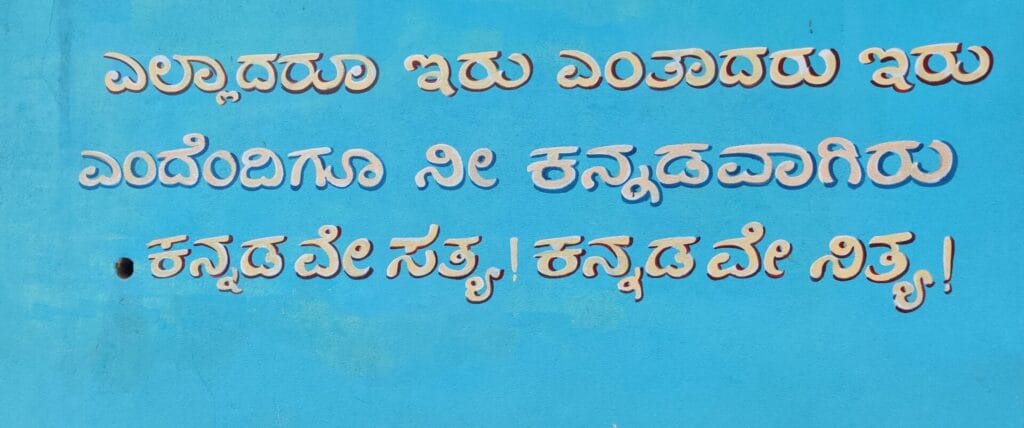

The protests calling for implementing Kannada signage in Bengaluru has once again opened up conversations and resentments in the city. Many Kannadigas and Kannada speakers are angry that migrants to the city do not learn the language, while many migrants feel they are targeted for not being local.

Read more: Kannada signage rules in Bengaluru: A history

Migrants in Bengaluru

According to the 2011 Census, approximately 44% of the people in the city are migrants. Most migrants are from within Karnataka or neighbouring Southern states. This is followed by migrants from Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Tripura and Manipur. These figures are over a decade old; we haven’t had a census since 2011.

How can Kannada language be promoted within such a large migrant population? What is the state government doing to promote the language?

Migrants in the city are of broadly two types: Educated urban migrants, who arrive in the city with job prospects, and rural migrants, typically pushed out of their villages by economic distress. While the former tend to be employed in high paying white collar jobs like engineering, the latter are typically engaged in informal service work.

In the past decade, a number of private organisations and individuals have run classes and coaching centres teaching Kannada. Yet, tensions are at an all-time high in the city where Kannadigas and other Kannada speakers feel Hindi and English are replacing the language.

Manje Gowda, an auto driver from Hennur, says that he is frustrated by North Indian commuters always defaulting to Hindi. Manje Gowda can speak Hindi, but he is not comfortable in the language. “I make an effort to speak in Hindi but they [customers] don’t make an effort to learn some Kannada,” he feels.

Learning Kannada in Bengaluru

Chandan Gowda, sociologist, and the Ramakrishna Hegde Chair Professor of Decentralization and Development at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, notes that societal factors make it harder for migrants or non-native speakers to learn Kannada. “Usually, you learn a new language by speaking to shopkeepers, while taking public transport or autos or engaging with locals in a variety of other ways. With apps for everything, the need for that communication is lost,” he says.

Chandan also notes that technology allows migrants to insulate themselves from local cultures. “Cable television and inexpensive wi-fi allow the migrants from outside the state to be plugged into news and entertainment from their home states and insulate themselves from the cultural contexts they have moved into – this is an historically unparalleled situation. In the past, living in a new cultural setting saw higher levels of engagement with local society than we see now”

He observes that some migrant communities take the trouble to assimilate. “If you look at businessmen from the Marwari community not only in Bangalore, but anywhere in the country, they will always learn the local language. I have seen this happen in my own neighbourhood over the last few years. They organise Kannada classes for the members of their community who join them in Bangalore. They have evolved this ethic over centuries.”

Education system prioritises English over Kannada

Added to this, English also attains a higher class status reinforced by our education system. “If you go to any private school today, the medium of instruction is likely to be English. And typically, in these schools, learning English is reinforced as a matter of linguistic prestige, but that is not the case for other languages. So, children learn to communicate mainly in English unless a conscious effort is made by parents at home,” Chandan points out.

He notes that it is mostly government-run schools in the state that offer Kannada medium education – as well as Urdu, Tamil and Marathi – and only the non-privileged attend these schools. “Since many of these schools have poor infrastructure, and English is seen as key for professional success, Kannada language instruction has come to be seen as an option for the not-so better-off people and as a trap that anyone with the means to evade must do so.

This situation can of course be remedied with better state funding for government schools and a more innovative curriculum where English is taught as a language alongside other subjects and an urging of the private schools to evolve a more respectful orientation towards the significance of education in Indian languages.”

Blue-collar migrants fend for themselves

While white-collar workers can at least afford private classes, these options are rarely affordable to low-income or blue collar migrant workers. “I would love to learn better Kannada and even read and write,” says Rupa, but she laughs at the thought of going to a coaching centre. “I send most of my money home to my village and keep just enough for rent and food here.”

Most migrant workers in the service industry, like Rupa, rely on daily interactions. Jerome Bara came to Bengaluru in 2009 as a security guard. He is today an entrepreneur and has co-founded a domestic worker agency in Electronic City. Jerome learnt Kannada on the job, moving from location to location and speaking to people. But most of the domestic workers employed by his agency do not have the option of learning Kannada the same way.

“Most of our maids speak only Hindi and most of our clients also speak Hindi. Even Kannadigas manage basic Hindi or speak in English.” As most of the domestic workers working through Jerome’s agency are live-in workers, that is they live and work with one family, they have little opportunity to expand their knowledge of Kannada organically, he points out.

Can the government support such migrant workers in any way?

Karnataka Development Authority’s role in promoting Kannada

The state government formed the Kannada Development Authority (KDA) in 1994, a statutory body that was to oversee and implement the development and promotion of the Kannada language. The KDA is the body that drafted the recent Kannada Language Comprehensive Development Act, 2022, which mandates promoting Kannada language, providing jobs to Kannadigas and implementing Kannada signage rules.

A look at the KDA’s work plans since 2019 show that the organisation primarily spent money on scholarships and awards to Kannada students at the primary and higher education levels; giving awards to Kannada scholars and artists; ensuring the dissemination of government rules and policies in Kannada; supporting organisations that promoted Kannada culture; and felicitating legal professionals, including judges who wrote court judgements in Kannada.

The KDA and other bodies appear to be undertaking many activities to promote Kannada amongst students, scholars and Kannada speakers in general. However, in terms of facilitating language learning among migrants entering the city, the government appears to be falling short. I reached out to the KDA regarding the policies and programmes in place to facilitate Kannada language amongst migrants in the city.

Officials in the Secretariat for the Ministry of Kannada and Culture said they were not aware of such schemes and policies and directed me to Santosh Hangal, Secretary of the Karnataka Development Authority. He in turn directed me to M. Lakshmana, the media advisor of the Minister for Kannada and Culture. I was unable to reach M. Lakshmana to ask if any such schemes were in the offing.

Read more: Kannada movement in Bengaluru: A history with Chandan Gowda

Kannada language centres

The KDA also announced Kannada Language Centres in 2017. One such centre was to start in Mahadevapura zone of the city. But there is no information about the centres, their reach or how one can enrol. I also found not one mention of these centres in the workplans of the KDA.

None of the migrants I spoke to had heard of or come across any such learning centres in the city.

Currently, the KDA only offers some material on their website to teach oneself Kannada. The material is available in the form of 147 page PDFs that have lessons from English, Hindi, Telugu, Malayalam, Tamil and Marathi to Kannada. Those wishing to use these lessons must be literate in one of these languages.

Jerome feels that a more proactive approach and active learning centres are extremely important as migrants are here to stay. “Many of the young girls coming here, don’t wish to go back. Even if they get married, they will come back and settle down here,” he explains. Support from the government would go a long way in helping such migrants assimilate to the language and culture of the state better.

What Karnataka can learn from Kerala

However, the Karnataka government can look to the Kerala Government for inspiration. In 2017, the Kerala State Literacy Mission Authority started a scheme called Changathi. The word Changathi in Malayalam means companion or friend. The scheme aims to teach migrant workers to speak, read and write Malayalam and Hindi within four months. Much like Bengaluru, large numbers of migrant workers from states like Bihar, West Bengal, Assam and UP arrive in Kerala each year looking for employment. In Kerala, migrant workers are called guest workers in official parlance.

Under the Changathi scheme, migrants are offered classes five hours a week at learning centres across the state concluding with exams. The lessons are covered in a book called Hamari Malayalam [meaning our Malayalam in Hindi]. Over 2,800 workers took lessons in the first phase, including migrants from Nepal. The lessons cover topics such as health, worker rights, technology and the culture of Kerala in Malayalam. Apart from imparting the local language, the scheme also affords migrant workers literacy.