The population of Jews in India is on the decline but the iconic physical structures they have built in Bombay will preserve the community’s memory for a long time. “Bombay holds a very special place in the hearts of all Jewish people in India,” said writer Sifra Lentin, in a recent event titled ‘Uncovering Urban Legacies: The Jewish Diaspora in Bombay’.

A proud member of the community herself, Lentin gave the audience a rich introduction to Bombay’s Jewish heritage, the community’s social and religious life, and their contributions to trade, education, architecture, cinema and literature. The event was moderated by Dr. Manjiri Kamat, Professor of History and Associate Dean of the Faculty of Humanities at Mumbai University.

It is estimated that, currently in India, there are only 80 Baghdadi Jews and about 3500 Bene Israelis. Their numbers have decreased due to large scale immigration to Israel and other countries. In 2016, Maharashtra recognised Jews as a religious minority. Bombay has been home to Baghdadi Jews as well as Bene Israelis.

Lentin, who is a Bene Israeli, is the Bombay History Fellow at a foreign policy think tank called Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

Her talk was based on a wealth of academic research and personal insights that can only come from an insider within the community. “India’s Jews have never faced anti-Semitism,” she said, “with the exception of the Marrano Jews in Goa during the time of the Spanish Inquisition.”

The legend retold

Lentin narrated the story of a shipwreck, which is retold among Bombay’s Jews. “According to their oral tradition, the ancestors of the Bene Israel, fleeing persecution by Syrian Greek ruler Antiochus Epiphanes, were shipwrecked off the Konkan coast, near the village of Nawgaon, south of Bombay (now Mumbai), in the second-century BCE.” writes Gabriele Shenar in an article titled “Bollywood in Israel: Multi-Sensual Milieus, Cultural Appropriation and the Aesthetics of Diaspora Transnational Audiences.”

Early Jewish settlements

It is believed that these migrants settled down in the surrounding villages, and the local population began to call them shanwar telis. This expression literally means ‘Saturday oil pressers’. Observant Jews consider Saturday to be a day of rest, when they do not engage in work but devote themselves to spiritual pursuits. It is known as Shabbat or Shabbos.

Shanwar Telis is also the name of director Johanna L. Spector’s documentary film about their customs, rituals and ceremonies.

Dr. Neeta M. Khandpekar, Professor in the Department of History at the University of Mumbai, who was Lentin’s co-panelist at the event, said that these Bene Israelis “got assimilated in their new environment” and took on surnames reflecting the names of their villages.

Jews living in Dive became Divekar; the ones who resided in Chinchavli became Chincholkar, and so on. Similarly, Isaac David Kehimkar, who is known as “India’s Butterfly Man” gets his surname from a place called Kehim.

In Sara Manasseh’s article “Religious Music Traditions of the Jewish-Babylonian Diaspora in Bombay” (2004) published in the journal Ethnomusicology Forum, she writes about Arabic-speaking Jewish traders who settled in Surat – north of Bombay — in the 18th century. She adds, “During the 19th and 20th centuries, a growing community of Jewish merchants from the Middle East and Central Asia established itself in Bombay…This diasporic group comprised mainly Jews from Baghdad, and included settlers from Basra, Syria, Aden, Iran (Persia), Bukhara and Afghanistan.”

Also read: Co-creating Mumbai afresh via ComplexCity

Sir David Sassoon – the Jewish merchant

Talking about the Baghadi Jews, Lentin dwelt upon the legacy of Sir David Sassoon. He escaped persecution and came to Bombay where he achieved tremendous commercial success as a trader of opium and textiles, and became a beloved leader in Bombay’s Jewish community.

Lentin said, “His arrival encouraged others to follow suit. He was able to provide employment and basic amenities, homes and schools for his Jewish brethren, enabling them to maintain their Jewish way of life.”

Lentin emphasized Sir David Sassoon’s role as an institution-builder. He wanted to give back to a city that gave him so much. Manasseh writes, “In 1861, he built the Maghen David Synagogue in Byculla (Bombay), where his family first lived, and, in 1863, the Ohel David Synagogue in Poona, where he had his resort home. In 1888, his grandson, Sir Jacob Sassoon, built the Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue in the Fort area of Bombay.”

This building is not only a place of worship but also a tourist attraction. However, security has been beefed up after the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai.

Lentin, who is also a Trustee of the Sir Jacob Sassoon School in Byculla, said that synagogues were typically within walking distance of homes because observant Jews did not take public transport, handle money or use electricity on Saturday. In her article “Bombay’s Blue Synagogue, Restored” (2019), published by Gateway House, she talks in detail about the socio-cultural and architectural importance of the Keneseth Eliyahoo synagogue located in the Kala Ghoda art precinct.

While the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival attracts lakhs of visitors every year, not many are aware of its ties to Bombay’s Jewish history. In her article “The Tale of the Kala Ghoda” (2018), published on livehistoryindia.com, Anshika Jain mentions that the equestrian sculpture which gave this neighbourhood its name “was a gift to the city by Sir Albert Sassoon, a scion of the Sassoon family.”

The rider astride the horse is the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). The sculpture made to mark the prince’s visit to Bombay was relocated to the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan in 1965.

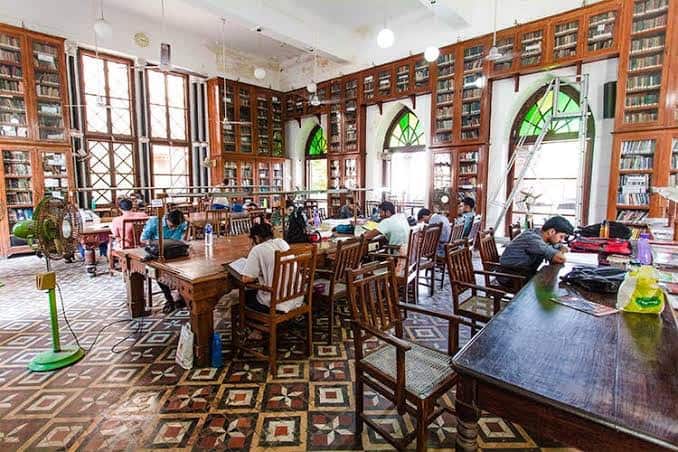

Which other examples of built heritage bear witness to the city’s Jewish history? Lentin and Khandpekar can list quite a few: Sassoon Docks in Colaba, Masina Hospital in Byculla, the Jewish cemetery in Chinchpokli, the Gate of Mercy synagogue in Masjid Bunder, the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room near Kala Ghoda, and the Haffkine Institute for Training, Research and Testing in Parel.

According to mumbaijews.com, a website maintained to publicize Oren Rosenfeld & Michal Lee Sapir’s new documentary film Mumbai Jews, the construction of the Gateway of India — one of Bombay’s most well-known heritage structures — was partly financed by Sir Sassoon Jacob Hai David, a prominent businessman who was a Baghdadi Jew. Apart from being the lead promoter of the Bank of India, founded in 1906, he also “served on the council of the governor general of India, on the Imperial Legislative Council and the Bombay Municipal Corporation.”

Jews in Hindi film industry

Actors such as Ruby Myers aka Sulochana, Ezra Mir, Farhat Ezekiel aka Nadira, Esther Victoria Abraham aka Pramila, Rachel Hyam Cohen aka Ramola, David Abraham Cheulkar, writer Josef David Penkar, and director Hannock Isaac Samkar made a mark in the Hindi film industry based in Bombay. Lentin said, “In those days, it was taboo for women to work in films. But, as a minority community outside the caste hierarchy, Jews were not too affected.”

A brief mention was also made of Nissim Ezekiel, a renowned poet, art critic and playwright who lived in Mumbai. The 90-minute event seemed too short, given the amount of knowledge the speakers wanted to convey but it was a solid and immersive experience to get people started.

Given the tiny population of Jews in Mumbai, very few residents of the city get to interact with Jewish people on a daily basis. That makes it all the more important to celebrate their presence, especially at a time when minorities everywhere are under threat and are made to feel unwelcome.

Also read