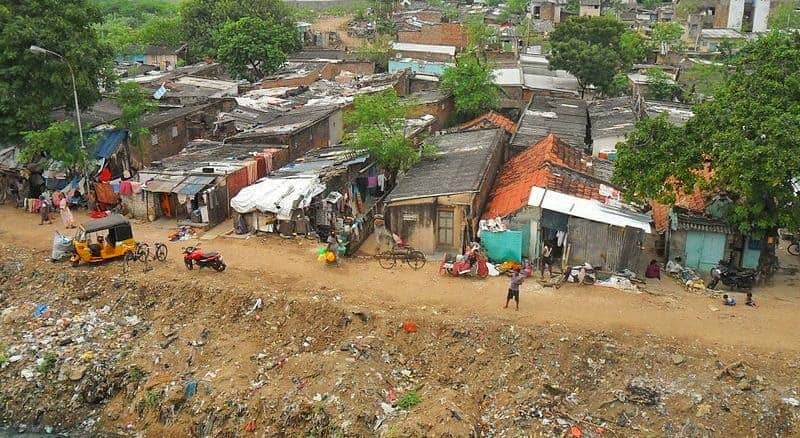

On October 16th, close to 50 families residing on the pavements near the Egmore Railway Station were evacuated and shifted to a temporary shelter near Pattalam, by the Chennai Corporation and the city police. The pavement dwellers alleged that they were evicted without any prior notice and that they had been forcefully moved. Several activists in the city had condemned this incident and also questioned the need for such hurried eviction without any prior notice and in the absence of any kind of arrangements made to permanently house the people. The irony is that this incident took place exactly four days after the Tamil Nadu Government released the Draft Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy, which states that people who are being resettled should be “treated fairly and humanely”.

The draft emphasises the need for public consultation as well as enumeration of families affected by eviction within three months from the date of publication:

“A designated officer shall conduct a public consultation regarding the draft Rehabilitation and Resettlement Scheme in the affected areas on a suitable date after 15 days from the date of issue of such Scheme. Wide publicity should be given about the date, time and venue of the public consultation. The designated officer should maintain a record of objections and claims raised in the public consultation.“

Read more: Why COVID proved to be a greater challenge in Chennai’s resettlement colonies

Citizen Matters spoke to Antony Stephen**, Assistant Professor, Department of Social Entrepreneurship, Madras School of Social Work (MSSW). Professor Stephen, a “migration specialist”, has been working on the issues relating to migration for the last 12 years and in this interview, he speaks about the draft resettlement policy of the TN government, its implications for the slum dwellers of Chennai, housing for the urban poor in general. Here are excerpts from the interview:

What are your thoughts on the Draft R&R policy released by the government recently?

I’d like to point out that this draft was initially discussed in 2010 during the end of the then ruling DMK government’s term. But they could not move forward with it as the AIADMK government came to power in 2011. However, after the new DMK regime led by MK Stalin took over earlier this year, they had informed through a policy announcement that they want to work on the policy of evacuation with a more humane approach, which is very much appreciated. But we have our concerns with the draft policy.

Firstly, when the draft was released on October 12th, it was in English, which was a bit of a problem because when we go for community consultations, how would the local people understand the policy if it is not in Tamil? After we academicians, activists along with the Communist Party of India (Marxist) pressured the government, they translated the draft into Tamil hurriedly, but the translation was very technical and it was not at all easy for the layman to understand.

Secondly, we are concerned about the limited time period set by the government for the consultation of the draft policy. The deadline to submit the suggestions for the policy was November 3rd, which gave people only 15 days to consider and revert. For other policies, they take months to frame a draft, and that too after plenty of consultation, so why such undue haste in this case?

I’m hoping that the government is not going to use this policyfor large scale eviction or evacuation of a lot of people from the city to implement their Singara Chennai 2.0 programme. Now, a question arises whether people living in the slums are also going to be involved in Singara Chennai, a programme that has seen an allotment of Rs 500 crore. That is a political question we have to ask, because the policy itself states that it was drafted with an empathetic perspective.

You were also invited to offer your suggestions for the draft policy. What were your suggestions?

I suggested that there should be a scientific approach when it comes to resettlement and rehabilitation of people. For example, the use of Geographical Information System (GIS)-based technology for mapping the location where people are currently living and identifying the government land around these places that has been encroached upon or lying unused. This land can then be used as government property and can be converted into areas for resettlement. But to make that happen, I feel that there is a need for proper data regarding such land.

Read more: Saving lakes in Chennai: Why maps and physical markers are critical

How do you see the policy being implemented in a place like Chennai with its infamous history of eviction?

I feel that the intention is good, but the experience over the last ten years has not been positive. The government has to include the economically and socially backward sections of the society in their policies, planning and in the smart city development projects as well, because homeless communities are also increasing. So all these policies have to be looked at and implemented from the perspective of increasing migration, increasing homelessness, emergence of more urban settlements and so on. So if the government has no adequate or concrete plan for them, then there will be continuing tension. There will be new slum communities created and again the government will have to evacuate them some years down the line and the cycle will keep repeating itself.

What, according to you, could be a solution to this continuous cycle of evictions and issues regarding resettlement and rehabilitation?

I strongly feel that this is true of the whole process of urbanisation as is taking place now, not just in Chennai but across the country. Slum eviction is an inevitable measure, but you need to have a proper and humane resettlement and rehabilitation policy. You see, people from rural areas migrate to urban areas for various reasons — employment, livelihood, better education, better health facilities. And we cannot tell people not to migrate. If the rural areas were equally developed, then migration would have come down but in countries like India, urbanisation is an ongoing process. And it’s definitely going to be a challenge for Chennai especially with regard to providing affordable housing for the people.

What are some of the housing models that could work in Chennai for resettlement?

At the moment, the TN government is constructing multi storeyed apartment complexes for the rehabilitation of evicted families. This is actually a good model where more people can be accommodated. But the authorities have to ensure that the quality of construction is good; they should not take public money for granted.

Secondly, there are housing models that can be experimented with on river beds like the Cooum river, for example. People say that you must not live near river belts at all but It is a problem only if the houses are near the river, at the same level. It’s possible to provide housing near the river by creating elevated platforms on a strong foundation and building houses on this foundation. This can be expensive, but it’s worth attempting.

But I also feel that the government should improve the amenities and facilities in rural areas. This way, migration to urban areas can be checked to some extent at least.

How has your experience in engaging with the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (TNUHDB) been? Do you feel that there is any need for reforms there?

I specialise in ‘Community Development’ and I have had to engage with the TNUHDB, which was previously called the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board, on many occasions. Earlier, there were more staff from the Community Development sector in the slum clearance board. Now, the number has come down and there are plenty of vacancies. These were the people who used to engage a lot with the slum community and act as a link between the government and the people. Unfortunately, now the board does not have adequate manpower to do this. If more human resources are appointed by the government in this section, it will help in rendering better services to these communities.

What do you feel can be done for the long term development of local communities?

I think that the government must allocate more funds for habitat development and they must also take steps to ensure that people from slum communities can provide services to the rest of the urban community. Community development structures or institutions should be created — for example, in countries such as the United Kingdom, there is a community development council. Of course, we have elected representatives but that’s more of a political role. Beyond that, a local community development council needs to be established to ensure development of local areas. That’s the only sustainable solution for this.

** Errata: Professor Antony Stephen had been mistakenly referred to as Professor Antony Stephens in the first published version of this interview. We apologise for the unintentional error.