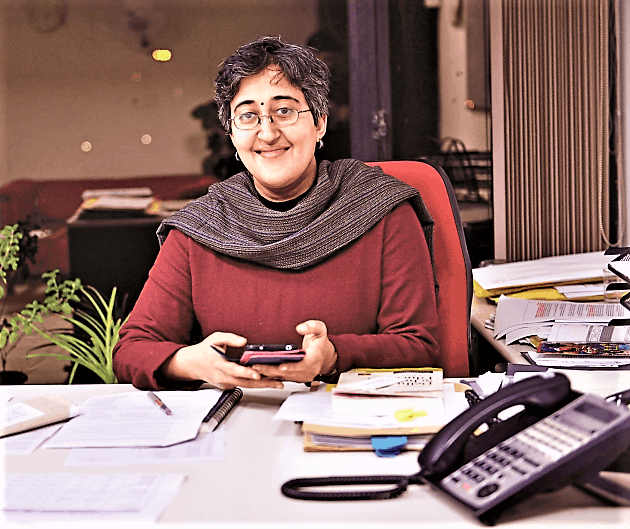

Atishi Marlena’s soft smiles belie the steely timbre in her voice when she speaks of issues. She is the point-person for education and has made it a central electoral plank for the fledgeling Aam Aadmi Party governing Delhi. Though she was “dismissed” as advisor to the Education Minister Manish Sisodia by the Centre in April 2018, she had by then spearheaded eight key projects, calling for 120 meetings – almost eight per week – since the beginning of the year.

Atishi was christened ‘Marlena’ as a fusion of ‘Marx’ and ‘Lenin’ by her leftist Delhi University professor parents, though she recently dropped the second name due to electoral compulsions when a whisper campaign dubbed her a ‘Christian’ and foreigner. Her impressive educational honours include topping Delhi University as a history undergrad at St. Stephen’s (2001), pursuing Masters in Oxford University as a Chevening scholar and joining Magdalen College, Oxford, as a Rhodes scholar (2005).

She explored teaching at Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh. After a year, she dabbled in organic farming and other progressive education systems and a number of non-profit organisations at a village near Bhopal. She then ran into a few AAP members who made her shift into politics from 2011 onwards.

Her track record as advisor to the Delhi Education Minister, Manish Sisodia, include upgrading Delhi government schools’ infrastructure, improving learning in three months through Mission Buniyaad, shaping the Happiness Curriculum, strengthening private school regulations and shooting up Delhi government schools’ pass percentage.

In the 2018 Class XII examinations, ToI reported that Delhi government schools recorded a jump in pass percentage of 2.37 percent over 2017, to stand at 90.64 percent. It was 7.6 percent higher than the national CBSE average, showing the best results in 20 years. HT reported a rush to join the state-run government schools rather than private institutions.

In the first week of February, Atishi was in Bengaluru to stir up enthusiasm for alternative politics. She says that though she is no longer an “official” advisor to the Minister, she is involved “informally” in education.

Citizen Matters caught up with her over a chat.

The educational transformation in the government school scenario in Delhi over the last four years seems to have been impressive. What do you see as the biggest change on the ground?

See, I think the biggest difference that we brought about was in the mindset of people. For the first time, we managed to make people think that government schools can change, and can work. Till a few years ago, people believed that they wouldn’t. Teachers, parents and students — none of them believed that these schools could make things happen. Only those parents who had no other choice or no disposable income would send their children to government schools. Things have changed now.

A child in the 7th grade told me that she is less affected by her worries, now that she is exposed to meditation in the Happiness class. I was surprised, what possible worries could a child as young as her have that would affect her so much? Her answer astonished me even more. She said that her family sends her brother to a private school as it is believed that a boy should get better education. That inequality really used to bother her. But after having been exposed to mindfulness in the Happiness class, she is able to recognize that it is her parents’ conditioning that they cannot overcome. Also the fact that her school is better than a private school in almost every way; so, there really is no need for her to feel bad about her situation.

Students in government schools have emerged as toppers in the Board examinations, some of them outperforming private school students; how do you think that happened? Was it due to changes in the infrastructure, syllabus, attitude, approach or teaching?

As I see it, there are three major pillars that we have established to build and hold up the educational structure. Firstly, infrastructure and maintenance. Earlier, there was shortage of infrastructure: the quality of government schools was poor and the schools were very, very dirty and badly maintained. So that is one thing that we brought about – we expanded the infrastructure, improved it and made sure that the schools were clean. We also built 8,000 new classrooms and are in the process of building 11,000 more. The quality of construction is much better, the schools are far cleaner. Every school has an estate manager who is responsible for ensuring cleanliness.

Improved infrastructure also creates a greater sense of dignity and pride – for students as well as teachers. For the first time, they felt that someone cared about their schools. And so the effort and self-belief of both students and teachers has shot up.

Next, we improved accountability. Earlier, there was virtually none. No one ever asked whether teachers were coming to class or not, taking up lessons or not. For the first time, we improved accountability by making parents part of the governance. School management committees, which exist under the Right to Education Act, are virtually defunct in all parts of the country. Those have been improved. We have been having regular parent-teacher meetings so that there is greater local accountability. That is one major change that we have ushered in.

The third factor has been the improvement in the quality of teacher training. We have invested heavily in this area. Earlier, the budget for teacher training was Rs 10 crore. We have increased it by ten times to Rs 100 crore. Our principals and teachers have been sent to some of the best organisations in the country and the world. They have been to IIM (Ahmedabad), Harvard University, Cambridge University, National Institute of Education.

How many teachers?

So far, at least 500 to 600 principals and teachers have been sent abroad on training programmes. I think almost all principals have been trained so far in IIM-A. We have also got a cadre of 200 mentor-teachers. Each mentor-teacher takes on the responsibility for five schools, in terms of improving classroom practices. Every school has someone called a teacher development coordinator, who plays a key role in improving process and practice.

All these things taken together have led to the transformation.

Are your schools very different from the Kendriya Vidyalaya (KV) schools, which are also run by the government?

Kendriya Vidyalaya schools are run by the Central government. They are smaller in number compared to the government schools, but KVs are definitely some of the better-run government schools. I think KVs have shown the fact that governments can run good schools if they want to.

What about the medium of instruction in Delhi government schools? Is it still Hindi, or have you introduced English?

The medium is still predominantly Hindi, and in some schools, English. But we have started running spoken English courses for students from Classes 10 to 12 during summer vacations, so that these students, when they go out into the world, do not feel that they are in any way less equipped than students from English-medium schools.

Do you personally believe that there should be a change in the medium of language?

I think that is something that needs greater thought, because studying in the mother tongue is important for the child’s learning. But then again, English is also important from the employment and job market perspective.

There is usually a lot of anger among regional language lovers whenever there is any suggestion for a change of the medium to English…

Well, we really need to maintain a balance. I don’t think it is an either-or situation.

What about co-curricular activities in Delhi government schools?

Yes, we have introduced a lot of co-curricular activities. We have summer camps, art, music, sports coaching classes….

Do you find that this makes children more eager to come to school?

Yes, of course.

What about those children who are employed in the labour market? There must be a number of students working elsewhere?

Definitely, there are a lot of children who are employed somewhere. The children who come to these schools are from some of the poorest sections of society and after school, many among them have to go out to sit by the vegetable carts with their parents. There is no escaping the fact. For us, the goal is to ensure that these children now have a better chance to move ahead in their lives than their parents did.

A lot has been said about the ‘saffronisation’ of history in textbooks in the last four years; what is your take?

Yes, it is an important political point, but I think it is an overrated issue. I think we have much bigger challenges. There are children coming to our schools who don’t even know to read or write. I think it’s more important for us to debate and find solutions to basic questions.

I’m not saying that saffronisation is not a concern. Of course it is. We need to have democratic values taught to us. But I think we need to address basic issues more urgently – Do our schools have enough money? Do they have enough teachers? Do they have desks to sit on? Are teachers regularly coming to class? Are students learning? Let us first address these questions, then we can address the issue of politics in history textbooks.

Critics say that content (of such kind) creates hatred…?

The hatred around us is not because of history text-books, but it’s now because of the kind of politics in practice all around us in the country. Politics is dividing the nation by caste, by religion. This is a country where people from different communities and religions have lived together harmoniously for centuries. But now politics is tearing communities apart for the electoral gains of political parties.

In April 2018 you were sacked. Have you been able to do as much in state education after that?

In an informal capacity, yes. I have continued to be involved in education. However, now, the degree of involvement is much less, because I’m going to contest elections.

So what do you want to do (if and) after you win the elections?

Parliament is where a lot of questions on education are debated and discussed. But I don’t think anyone in the House knows what are the real issues within the domain today. Having worked in education all these years, I think that if I do win the current elections, it would be a win not only for myself, but also a win for an important discourse in politics.

So far, elections have been won on the basis of caste, religion, money and liquor. If education can become a central issue, and elections can be won on the plank of educational reform, that in itself would be a great, positive shift for politics.