On the occasion of India’s 72nd Independence day, when Bengaluru should have observed the plastic ban effected two years ago on March 11, 2016 through a gazetted notification, bulk manufacturers of the national flag remained unaware of the environmental impact of using common polyester fabric to make these flags.

Despite the Ministry of Home Affairs issuing a notice advising state governments to keep a strict vigil on the usage of plastic flags this year, the purpose was defeated, primarily because most vendors did not grasp the real implication of making and selling polyester fabric flags. The manufacturers, distributors, and shops often mistake polyester, a petroleum product, to be an alternative to plastic, either due to misconceptions about thin plastic or the fabric’s external resemblance to cotton.

Some of the popular go-to avenues to buy national flags, such as Flagkart and Roopa Textiles did reduce selling flags made from poly-vinyl chloride, the same chemical used to create banners and posters. But a visit to a few of these stores in the city revealed that they have moved towards using polyester fabric, most often unaware that the latter is equally non-biodegradable as plastic.

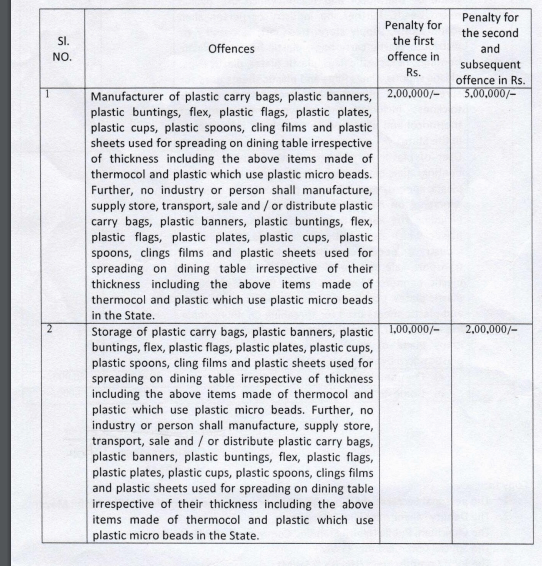

However, the Central Business District area was still dominated by street vendors selling the usual plastic flags, in complete violation of law. The 2016 notification (image shared below) says that manufacture of several plastic products, including flags, is an offense under Section 5 of the Environmental Protection Act, 1986 and could attract a penalty of Rs 5 lakh in repeat offence cases.

Executives and sales people say polyester is the lesser evil

Roopa Textiles on Poornaiah Chatram road sells Indian national flags, political posters and banners in plastic, silk and polyester. On August 14th, the shop was visited by roughly 100 customers. “During this time of the year, we get a lot of customers. I purchase around 2000 Indian flags from an Avenue road vendor, and sell each flag at Rs 20. I have now switched to using thinner plastic material. The flags are made of cloth (polyester). I have no idea about the end result on the environment, I am just trying to run a business,” said the owner in a brazen tone.

From factories in Mumbai and Hyderabad, Flagkart in Jayanagar receives a supply of 25000 Indian flags throughout the year. The owner uses his house as an office to run the business, selling medium sized (2′ X 3′) Indian flags costing Rs 1000. Here once again, there was lack of clarity on polyester being just another form of plastic. “We do not have plastics, we use only printed cloth material,” said the owner.

The Flag Company considers itself to be one of the premium green companies in India operating in seven cities, with its head office and manufacturing unit in Mumbai, supplying flags to 18 airports in the country and the Indian navy, while also exporting flag-varieties to South Eastern countries. Corporate flags with logos are ordered by Bengaluru institutions online.

Indian national flags make up a very small portion of their business. Usually, the company gets flag orders two weeks before Independence Day but demand was low this time. Director, Dalvir Singh Nagi says, “My company buys the yarn, weaves the flags and uses water-based ink for coloring. Polyester is recyclable material, which can be dyed and reused, or made into bags. Our material is 100% polyester in 150 GSM, with no PVC value. We stay away from flexes. ”

A flag hanging outside Roopa Textiles in Balepet, made from polyester material. Pic: Seema Prasad

A possible alternative

Apart from the obvious cotton and paper alternatives, there could be another solution which would be environmentally less harmful than using virgin polyester, at least on a relative scale.

Royal Challengers Bangalore, the IPL team, is known to make good use of Polyethelene (PET) bottles discarded during matches to create polyester yarn, which are ultimately used to make T-shirts for the team. It serves as an example to show that polyester yarn can be made from recyclable plastic, as opposed to manufacturing it in huge quantities in factories from virgin polyester.

Associate Professor of Amity University (Gurgaon), Naveen BP, who completed his PhD in Solid Waste Management (SWM) from the Indian Institute of Science (IISC), says that the best way to reduce the life span of the plastic in polyester is to recycle it before it reaches the landfill. “50% of its life as a form of plastic gets automatically reduced due to the processing it is subjected to,” he says.

Polyester yarn made from PET bottles could also be used to make these flags. RCB spokespersons explain the chemical process in three steps.

Step 1: Waste PET bottles are first cleaned by removing the labels and caps, after which the bottles are washed and cut into small pieces called flakes. The flakes are fed into a recycling unit . Here, the pet flakes are dissolved into a chemical (Mono Ethylene Glycol) which is a basic constituent of polyester.

Step 2: Once the flakes are dissolved, the chemical is subjected to a filtration system where all types of contamination (like paper particles, other plastics, metal dust, carbon ink , glues) are removed. The filtration systems involve the usage of activated carbons, leading to the formation of uniform polyester raw material.

Step 3: After the filtration the MEG is separated from the polyester and it is reused after cleaning the same. From this point, the raw materials are again converted back into polyester by polymerization process and then it is converted into a polyester filament yarn.

The aftermath of using polyester

Environmentalist AN Yellapa Reddy insists that the only recommended biodegradable alternatives should be cotton and paper, especially for a one-day affair such as observance of Independence Day and polyester fibre should be avoided at all costs, despite its deceptive thinness.

“Any petrol product is certainly harmful, and finally results in the bio accumulation in nature nonetheless,” Reddy said. He cited the Extended Product Responsibility (EPR) guideline mentioned in Plastic Waste Management rules (2011), which puts the onus on the manufacturers for declaring the materials used. “The effects of polyester fabric are very intelligently hidden in jargon for profit-making. It is the duty of the product makers to disclose its properties in details, and methods used to recover the material,” he added.

Saahas Zero Waste, a waste management company, has found ways to make products from Multi-Layered Plastic (MLP – a mixture of two or three layers containing paper, metal, aluminum, and polymeric materials). CEO Wilma Rodrigues attributes the misinformed perception of polyester fibre being less hazardous to the fibrous touch of cloth, similar to cotton.

The organisation has its own Material Recovery Facilities that aggregates polymers from various sources (factories, hotels or malls) and separates biodegradable components, through shredders, screens and magnets. The collected material is eventually sent to ACC cement kilns where non-biodegradable waste gets converted to fuel**.

“The process is arduous and polymers do cause problems for waste management companies. The cost is huge for collection, dispatch, and transport. We are lucky to have the means to do it, but that is not always the case for small-scale industries. As of now, we do not have an estimate of polyester material we receive,” she said.

The substance formed after separating combustible properties from MLPs which is used in coal power plants, cement and lime kilns in place of fossil fuels, is called Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF). So far, RDF facilities are present at the plant set up by MSGP Infratech Pvt. Ltd in Doddaballapur, where 30% of the waste can be converted to RDFs, finally sent to cement factories and the KCDC plant.

In 2015, the BBMP started to process plastics at the composting sites at Kannahalli and Sigehalli. But the municipal body has always had to deal with fires caused by massive amounts of accumulated RDF as the cement factory in Kalaburgi was not accepting the waste without heavy transportation charges. The plants were pulled up for not functioning at optimum levels recently.

“Enforcement has always been an issue with BBMP. Polymers are on the list of banned items issued by them. It is a well known fact, ” explained Rodrigues

Plastic awareness drives concluded in 22 constituencies

Meanwhile, the Environmental Management & Policy Research Institute (EMPRI) has been roped in by the BBMP to conduct plastic awareness drives in all of the city’s 28 constituencies. This commenced on August 1st.

B Basavaraj, Head of Training at the capacity building wing of the Department of Forest, Ecology and Environment recommends the use of khadi cloth in the manufacture of flags. The institute concluded its plastic awareness drives in Bommanahalli and Bengaluru South constituencies one day prior to Independence Day. During the drives, the EMPRI staff showed videos and held demonstrations, explaining the harmful affects of plastic.

“We have finished conducting plastic awareness drives in 22 constituencies till date, and will be finishing 6 more shortly. Hotelier associations, vendor associations and BBMP officials, amounting to a good interactive crowd of 50 people are present during the power-point presentations and demonstrations on alternative options, ” said Basavaraj.

One hopes that these exercises will yield fruit by the next Independence Day, so that we can completely eliminate the use of environmentally harmful flags and banners. True patriotism can best manifest itself through a more informed and responsible commitment towards the planet and in turn, our own motherland.

Dr Sandhya of BBMP showing the crowd in Yelahanka plates from areca material, the alternative to plastic, during an on-going awareness drive. Pic: EMPRI

[** Errata: There was a factual error in this statement in the originally published version of the article that has since been corrected.]