I travel across cities in India for work and leisure, but Mumbai has always been important to me, as I have family and friends in the city. Coming from Bengaluru, the city’s heat and humidity have not really been in my favour. Outdoor walks during the evenings always help me recover from my physical and mental fatigue. Recently, taking my son to a nearby public space – a park near our house in Vashi, Navi Mumbai – has become my routine. ‘Gorakhnath Shivram Palve’ is a neighbourhood park, one of the many in this planned extension of Mumbai. Visiting a new park with no social circle to distract me, I became immersed in my 2-year-old son’s play for the first few days.

Very soon, I realized that it was not just my son who felt secure and happy being here, but I was equally transforming into a child in this space. This got me thinking about what really made this public space special compared to several other spaces I have visited over the course of my work as an urban planner? Or perhaps the question should be: What makes a public space safe and inclusive?

Location of public space at a stone’s throw distance

The first step towards creating a successful public space is its strategic location with respect to its surroundings and the ability for locals to access the public space within 10-15 minute walking distance within the neighbourhood or from high activity zones like schools, colleges, workplaces, etc. It was very enticing to watch a few school kids take a pit stop to finish their mini parkour run within the park, before they headed back home. More people using these spaces will create a sense of ownership for the community and prioritise citizens in our public spaces.

Read more: Mumbai has less green than what masterplan shows: just 1 sq m per person

Ease of access to and within the public space

Public spaces should be easily accessible to all kinds of users, including children, senior citizens, and people with disabilities, often referred to as ‘universal accessibility.’ This includes elements like continuous footpaths with ramps, safe crossings at junctions, signages and others. This applies to the adjacent streets which are used the access the public spaces as well as walking areas within the public space.

Constant visual connect

The public space should office uninterrupted visual connection between different spaces including play areas, walking zones and resting spaces. This helps in bringing in a sense of security for the caregivers and provides freedom for kids to explore the space. I could keep my eye on my son as he explored the slides and swings, giving me enough time to finish my jog along the periphery of the park.

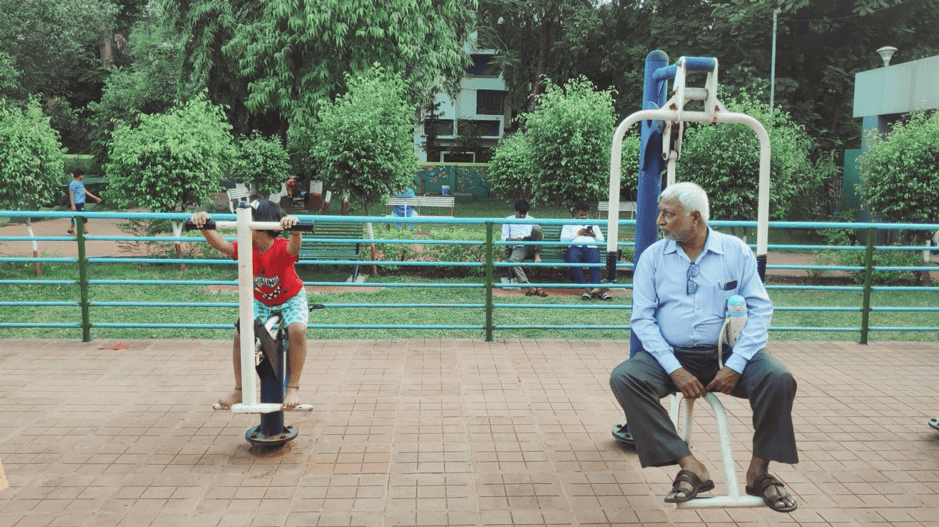

Age no bar

From a teenager kid doing pull-ups on my son’s (a toddler) slide or the local Ajji Bhai (grandmother) cherishing her dreams on a swing, all public spaces need to be safe and adaptable. Although there are specific design considerations required to design spaces and equipment for users of different ages, gender, and abilities; these elements can remain open and unrestricted for all types of users.

Parks should experiment on materials as well as designing the equipment and spaces, which are adaptable to diverse age groups.

Safety and health

This tops the list. The access streets for public spaces need to have a uniform and uninterrupted walking surface. The public space and its surroundings should be well lit to allow people to safely walk during evening and night. The space should provide and maintain basic amenities like toilets and drinking water, shaded structures, and trees for the safety and health of users. As the sun set, it felt like a drama to watch the transition of users, from kids to senior citizens to working men and women taking a break before they head home.

In conclusion, a public space should aim to provide a sense of personalization for every kind of user, but also retain its universality. As experts, sometimes there are more benefits to taking off the planner’s hat and evoke the child within us to design more equitable and inclusive spaces for all.

[This article was originally published on Linkedin.]