With ever growing and rapidly changing Indian cities, the gamut of issues that are affecting them are not only growing, but are becoming very specific to the local context. Decision-makers and designers are rethinking urban design to make cities more liveable and public spaces more accessible and safe. Tactical urbanism is gaining popularity as a method to tackle these issues.

What’s tactical urbanism?

Tactical urbanism is all about action. It is also known as DIY urbanism, Planning-by-Doing, Urban Acupuncture, or Urban Prototyping. This approach refers to a city, organisational, and/or citizen-led approach to building neighbourhoods by using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions to catalise long-term change. As the involvement of stakeholders is pivotal to the success of the project in such interventions, a participatory design approach is critical in tactical urbanism.

Read more: Who should govern Bengaluru’s lakes — the government or the community? Or both?

Participatory design is when all stakeholders and people affected by a particular project/intervention/policy are invited into the design process, to better understand, meet, and sometimes preempt their needs. It acts as a tool to gather and understand different perspectives to design best possible solutions to the challenges at hand.

The case of Sringeri Mutt Road

One example of a good tactical intervention where a participatory approach proved worthy is the case of the Sringeri mutt Road, Chennai. This intervention was facilitated by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. This is an interesting example of how involving the community in participatory design can shape the spaces they live in. It was a quick and cost-effective initiative aimed at enhancing road and personal safety in the neighbourhood, primarily from the point of view of women and children.

The project embraced three key principles:

- A practical orientation – with a specific focus on tangible problems: In this case, the goal was to improve safety by tackling the issue of abandoned vehicles and unauthorised parking, which were contributing to general degradation of the area and led to activities such as public urination and eve teasing.

- Bottom up participatory approach – with the affected people working together with experts and decision-makers: The ITDP India Programme undertook several site visits and held stakeholder consultations with frequent users of the street like local residents, students and teachers of the neighbouring school to understand the root cause of the problem. This helped build trust and accountability.

- Deliberative solution generation – joint planning and problem solving through a process of deliberation: Different organisations like the Chennai Traffic Police, Greater Chennai Corporation, civic action groups like Thiruveedhi Amman Koil Street Residents Association (TAKSRA) and Karam Korpom, Chennai High School (Mandaveli) and the ITDP India Programme came together to hear out concerns and find solutions.

Following the initial deliberations, the issue was addressed by first vacating unauthorised parking and then cleaning and painting the area. With the help of school students and the RWA, the street was transformed into a vibrant place by painting a portion of the road and compound walls in vibrant colours. Not only did this help increase pedestrianisation, as a result of the higher movement of people, the area became a lot safer for users. A post-implementation survey showed that 90% of the users who used the street felt an increased sense of safety.

Going about a participatory design event

Both tactical urbanism and participatory design work best for a small scale neighbourhood since problems and solutions are very site-specific. Every neighbourhood and project is different as are the people. Hence, participatory activities or programmes should be designed accordingly, to suit both the problem to be addressed and the participants.

The programme could have an opening activity to familiarise participants with each other and the project. That could be followed by activities for exploration of the problem and discussions, and end with a closing that reflects on and discusses the learnings. The most effective and the simplest way to conduct participatory design is through group activity.

Read more: How public spaces can be redesigned to make ‘unlocking’ safe in Bengaluru

Participatory design is not an exact science. There isn’t a singular way to design participation. The facilitator plays an important role. They need to be observant and agile. They have to lead the participants through the program, be quick in adapting and modifying the program if the participants aren’t responding in the desired manner.

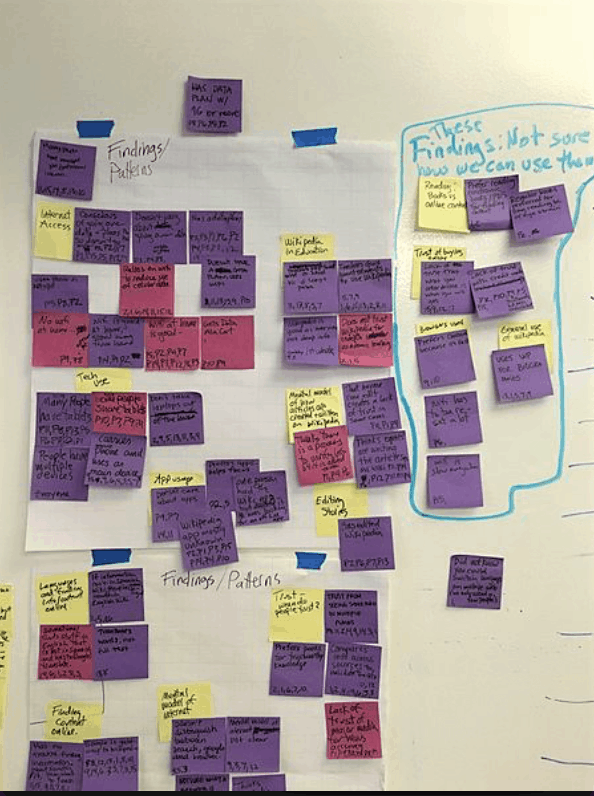

Below are a few examples of participatory activities that could be used for a tactical intervention:

1) Sociometry

Sociometry can be used as an ice breaker to extract basic information from the participants of the group. It can also be used quantitatively to measure and analyse the dynamics of the group and make affinity maps based on the issue at hand.

2) Community mapping

Community mapping is done to identify and locate spatial issues, locations, routes, landmarks, areas of focus depending on needs of the project. It can also be used to understand the relationship the communities/identities share with the place.

3) Problem wall and solution tree

A problem wall and a solution tree provide an overview of all the known causes to identify possible solutions. This can be a good way to help plan the project and bring out key focus areas, while factoring in the complexity of the problem and different perspectives to find solutions.

Say yes to participation!

Creative activities can be designed to engage with the community, probe them to think, vocalise, discuss and move towards solutions. It is important to remember that facilitators and their institutions have just as much to learn from the community as the community has to learn from us.

Participatory design is a way to make community engagement real. For designers, it is important to understand that we might be facilitating the process, but it is the communities’ stories and voices that need to be told and heard. Only then will there be real value to any tactical intervention. Ultimately, it is important for the community to feel ownership of their public spaces for a tactical intervention to truly serve its purpose.

[The author is a Mobility Champion for the #BengaluruMoving campaign with Young Leaders for Active Citizenship (YLAC). The #BengaluruMoving campaign aims to increase citizen engagement toward creating sustainable mobility solutions in Bengaluru. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.]