The voter data scam, uncovered by The News Minute (TNM) and Pratidhvani, has raised concerns over the breach of privacy and the misuse of voter data. At the heart of the issue is the actual voter data.

This is the first part of a series looking deeper into the implications of the Bengaluru voter data theft controversy.

Part I: Illegal voter data collection: Does it really matter? (this article)

Part II: Illegal voter data collection: How can we protect our privacy?

Part III: Illegal voter data collection: Frontline workers of election management

The crucial allegation against the NGO Chilume Educational Cultural and Rural Development Institute is that it collected personal information of voters in multiple constituencies, while posing as electoral officers from the BBMP. It is important to understand why this data was collected and why this is a cause for concern.

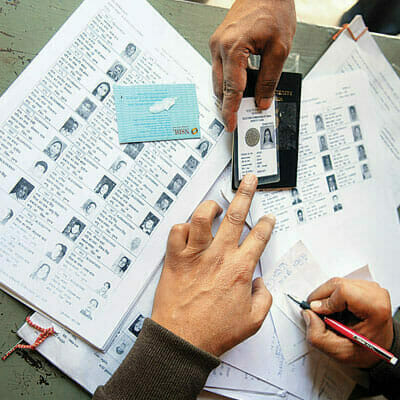

In the run up to every election, the Election Commission of India (ECI) undertakes an exercise where they check if the voter information is authentic, strikes invalid or fraudulent voters from the rolls, and adds new residents or freshly enfranchised voters on to the rolls. As part of this process, government officials called booth level officers are supposed to carry out periodic door to door verification of voters, which involves matching voter names, photos and documents to the actual residents.

Only current and retired government officials and semi-government employees can become booth level officers and they come under the supervision of the Chief Electoral Officer-Karnataka (CEO).

According to the TNM and Pratidhvani investigation, staff and vendors hired by the NGO Chilume were officially authorised by BBMP electoral officers, who report to the Chief Electoral Officer-Karnataka (CEO), to conduct voter awareness programmes in all 28 constituencies under the BBMP.

Chilume workers posed as booth level officers, who are in charge of checking voter lists at each polling booth, and illegally collected names, phone numbers, addresses, caste, mother tongue, marital status, age, gender, employment, education and even Aadhaar and Voter ID numbers of voters.

Data in politics

The founders of the NGO also ran a political consultancy firm called Chilume Enterprises and all of the voter data collected by the NGO Chilume was uploaded onto an app called Digital Sameeksha, designed by the political consultancy firm for their clients from various political parties.

Although political consultancy has only taken off in the last decade, today most parties hire them to run their campaigns, says Ajit Phadnis, Associate Professor at IIM, Indore. Phadnis, who co-authored a recent study on this subject, explains that these firms advise parties on political and communication strategies, handle their social media and conduct voter surveys using apps and technologies.

Political consultants use a variety of data to create effective political campaigns for their clients and personal information can be a goldmine. “Personal data, aggregated at the booth or ward level, is extremely useful to politicians, as it enables them to customize their local level campaigns based on the composition of voters,” he says.

The question that naturally arises is does this matter? While condemning the NGO’s actions, voter reforms activist and software engineer Commander PG Bhat points out that much of the data that Chilume collected with fraudulent credentials is already publicly available.

Electoral rolls published on the CEO-Karnataka’s website, can reveal names (and consequently religion and caste), house numbers, age and gender. “Once this data is available on the internet, it cannot be completely hidden,” he says.

However, such data is not always easy to use according to the political consultants that Phadnis interviewed for his study. The ECI publishes voter lists in PDF and in the local language making them difficult to search or analyse with computers according to Phadnis’ research.

Personal data from social media websites was also difficult to process at a mass level as it is difficult to match social media profiles with names of voters present in the voter list, according to him. It is because of the difficulties, Phadnis speculates, that parties and their consultants may be resorting to collecting personal data ‘directly’ from voters by conducting voter surveys.

Read more: The story of how I got my voter id in Bangalore

“However, the ethics of data collection mandates that prior to collecting personal data from people, the purpose for which the data is collected, and the planned use of the data needs to be disclosed,” he adds. Bhat argues that it would not be difficult for any politician to pay people to manually scrape this data off the election commission websites.

Collective harm

Srinivas Kodali, an independent researcher studying internet movements, points out that the NGO’s actions, conducted under the aegis of government officers, is a violation of citizens’ right to privacy and can lead to collective harm. “Will this harm an individual directly, I am not so sure.”

Rather than individuals, such data could be used to harm vulnerable communities, such as minorities, marginalised castes or women and lead to microtargeting, a strategy where political campaigns are tailor-made for people based on information about their activities, opinions and social networks. Kodali pointed out that Aadhar data and mobile numbers can be used to derive other information such as where voters work.

In the present case, Chilume workers were allegedly collecting voters’ opinions on candidates without masking their identity. Information which was then uploaded on to an app that could potentially be available to those very candidates.

In this case, voters with a negative opinion of specific political representatives or candidates could fear very real backlash. “If you think someone is not going to vote for you, you can try to have them removed from electoral rolls,” says Kodali. Indeed, TNM reported that residents from a Shivajinagar neighbourhood were threatened with deletion from the voter rolls by unknown persons posing as booth level officers in October this year.

Read more: If you don’t have your name on BBMP voter list, check it again!

Representatives from Chilume trust had also been arrested in 2017 on the allegation of illegally collecting voter data from the Byatarayanapura constituency in North Bengaluru. In this case, the NGO workers had collected mobile numbers of women and taken their photographs, sparking fear of misuse and sexual harassment among the residents of the area.

Bhat agrees that this is worrying and feels that the ECI itself has adopted poor practices that could jeopardise voters in this situation. During every election, the ECI provides data on political parties’ performance at the level of every polling booth.

“Every booth will have around 500 houses. It is not difficult for anyone to find out the political leanings of people in such a scenario,” he says. “We have been saying the ECI should not publish booth level vote-share data for a long time.”

Bhat also laments the lack of scrutiny into the office of CEO-Karnataka. “Political parties are blaming each other, and people are looking at the BBMP, but this is the responsibility of the office of the CEO-Karnataka who has received awards for poll management.”