Chennai has approximately 8,331 homeless individuals concentrated in hotspot areas and along major roads across 15 zones. Notably, 69% of this population consists of families who have lived on the streets for generations. Despite this high number, a recent study by the Information and Research Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC) reveals that the city doesn’t have a single shelter for families.

In January 2023, Citizen Matters visited five GCC homeless shelters in Chennai to identify operational gaps. These shelters cater to boys, girls, the elderly, and individuals with mental illnesses. Yet, the funding for their operation and maintenance is inadequate and uniform, regardless of the distinct needs of each group. Many children stay in shelters while their parents remain on the streets. The IRCDUC study indicates that about 1,430 children live in street situations alongside their families in Chennai.

Meanwhile, several studies have documented the issue of homelessness and the need for safe shelters. The GCC conducted an enumeration of the homeless population in 2018, followed by a survey by the Madras School of Social Work (MSSW) in 2022. Nearly two years later, IRCDUC conducted a Rapid Assessment Process in September 2024 to evaluate the profiles and needs of homeless individuals. This assessment highlighted significant systemic gaps and underscored the necessity for an intersectional approach.

Who is considered ‘homeless’?

For census purposes, ‘houseless households’ are defined as people living in the open — on roadsides, pavements, under flyovers, in places of worship, and in similar locations. This definition was expanded by the Supreme Court in the Writ Petition (Civil) 196 of 2001 to include individuals residing in shelters, transit homes, and temporary structures with or without walls, under plastic sheets, thatch roofs, pavements or parks and other common spaces.

Profile of Homeless Persons in Chennai

The study also indicates that the number of nomadic tribes may be underreported, as families residing in areas like Marina Beach and Besant Nagar are often unwilling to disclose their identities. Among the 910 intra-state migrants identified, most hail from Salem and Vellore and are engaged in seasonal work. Families living in Velachery (under bridges) originate from Athur, leaving their children and elderly relatives behind in their home villages.

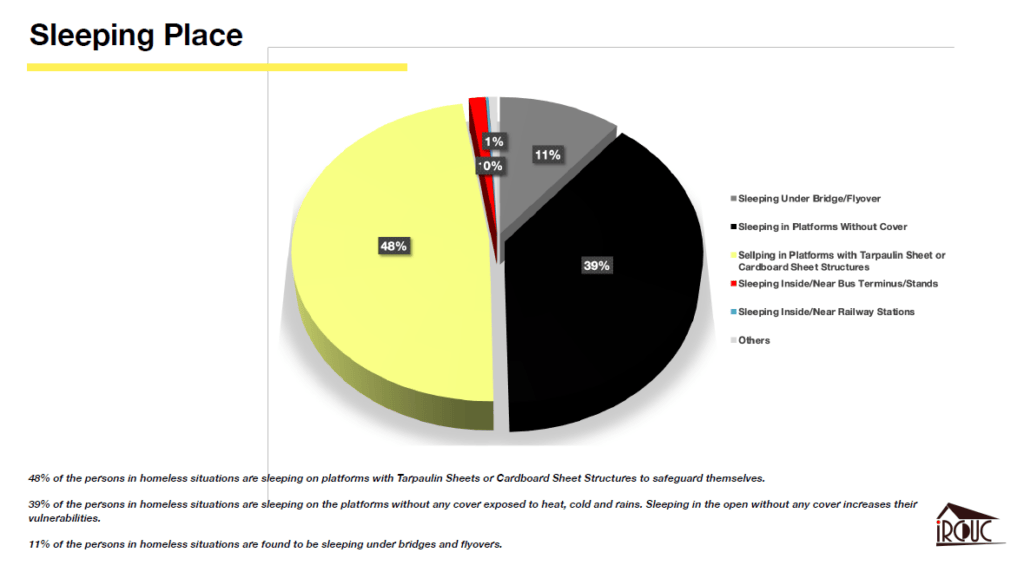

Where do the homeless people in Chennai sleep?

The right to shelter is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, encompassing adequate living space and basic amenities. The study reveals that 48% of homeless individuals in Chennai sleep on platforms using makeshift covers like tarpaulin or cardboard, while 39% sleep without any shelter, exposing them to harsh weather conditions.

Findings from IRCDUC’s Rapid Assessment Study

Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) currently operates 49 shelters in partnership with NGOs. However:

- Of the 49 shelters, only 37 shelters are available for homeless individuals, as 12 are reserved for attendants of patients in government hospitals.

- Elderly individuals constitute 11% of the homeless population, yet only three shelters cater specifically to them. This highlights the urgent need for interim shelters for seniors, as outlined in the Tamil Nadu State Policy on Senior Citizens, 2023.

- Discussions with transgender groups indicate a pressing need for dedicated shelters in South and North Chennai, as only one exists in Central Chennai.

- Families who have lived on the streets for generations struggle to access state housing programmes due to challenges in contributing to the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (TNUHDB). Additionally, there is no rental housing scheme for migrants, and access to housing entitlements remains a challenge for those in shelters.

Read more: A wishlist to tackle homelessness in Chennai

Recommendations

- Shelters are seen as the only solution for addressing urban homelessness. The Shelter for Homeless Scheme is currently a stand-alone initiative implemented by ULBs. To effectively address urban homelessness, shelters must be part of a broader, intersectional strategy.

- While we come across many videos on social media revealing the faces of those rescued from the streets, the study recommends the government formulate uniform guidelines for ensuring a dignified rescue process by GCC and Greater Chennai Police (GCP).

- With Chennai facing more extreme weather, there is an urgent need for a heat management plan and a monsoon strategy to safeguard homeless individuals during severe climate events.