Unlike the centre and state budgets, there’s little discussion on municipal budgets in India. Multiple media reports highlight that the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is India’s richest municipal corporation with a budget higher than most states. But there’s little awareness on what the budget entails, how BMC earns or spends its money, and how can a citizen keep track of its revenue or expenditure.

Here’s a look at some of its core features before BMC presents its 2021-22 budget.

Who prepares the budget?

Budgets at the centre and state are prepared and presented by the respective Finance Ministers. But the Municipal Commissioner is at the helm of BMC’s budget. Mumbai’s Standing Committee, made up of elected representatives, debates on the budget and makes changes. More often than not, these changes are minor in nature. Experts argue that like at the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha level, the budget should be a responsibility of the “elected body” of BMC.

Read more: Funding Mumbai’s municipality: many options, no solutions

Reading the budget

BMC uploads many documents related to its budget on its website. These include the Municipal Commissioner’s speech as well as budget highlights, books and provisions. But navigating and making sense of these documents on BMC’s unfriendly website is challenging.

One of the most important documents on the BMC website is “Budget Estimates at a Glance”. Here, the budget is divided into four subheads: A B G and E, each of which is then divided into fund codes.

If we look at the 2020-21 budget, Budget Estimate A, Fund Code 11 is the General Budget. It details income, expenditure, capital receipts and project works of a variety of departments. Under the Roads and Traffic department, an estimated income of 837.92 crore, expenditure of 679.73 crore and project work of Rs 1600 crore is shown. The Education Department shows an estimated income of Rs 130.62 crore and an expenditure of Rs 173.02 crores.

Then there is Fund Code 12 which is the Health Budget. This includes income and expenditure of not only the health department but also all the hospitals in Mumbai. Apart from General and Health Budget, there are two more fund codes under Budget Estimate A: Provident Fund and Pension Fund paid to the BMC staff.

Budget Estimates B shows income and expenditure of Improvement Schemes, Slum Clearance, Slum and Improvement. Budget Estimate E is the Education Fund and Budget Estimate G is Water Supply & Sewerage. Estimates of the income and expenditure of the Tree Authority Department are marked separately.

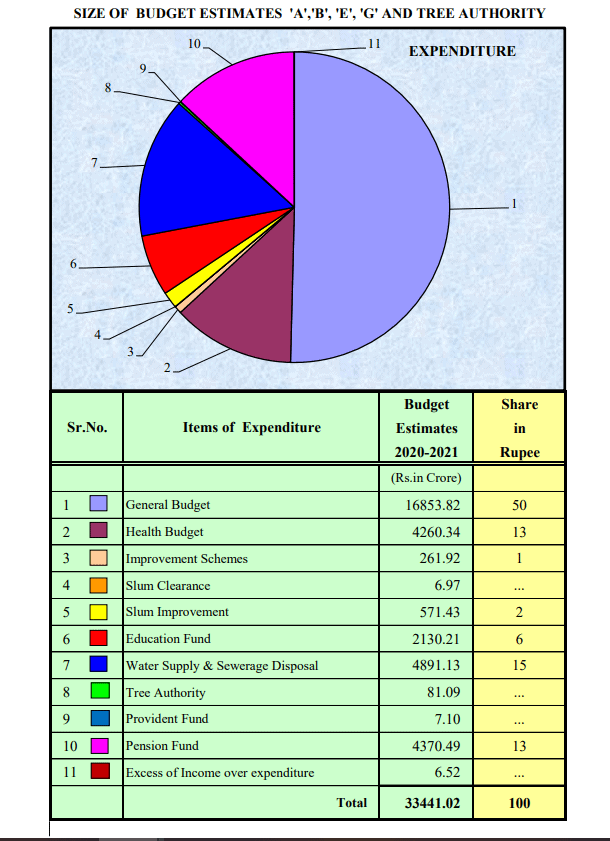

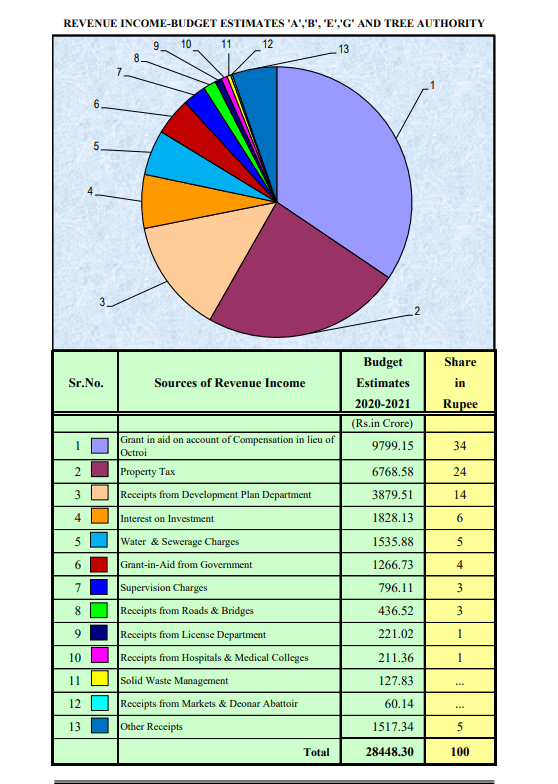

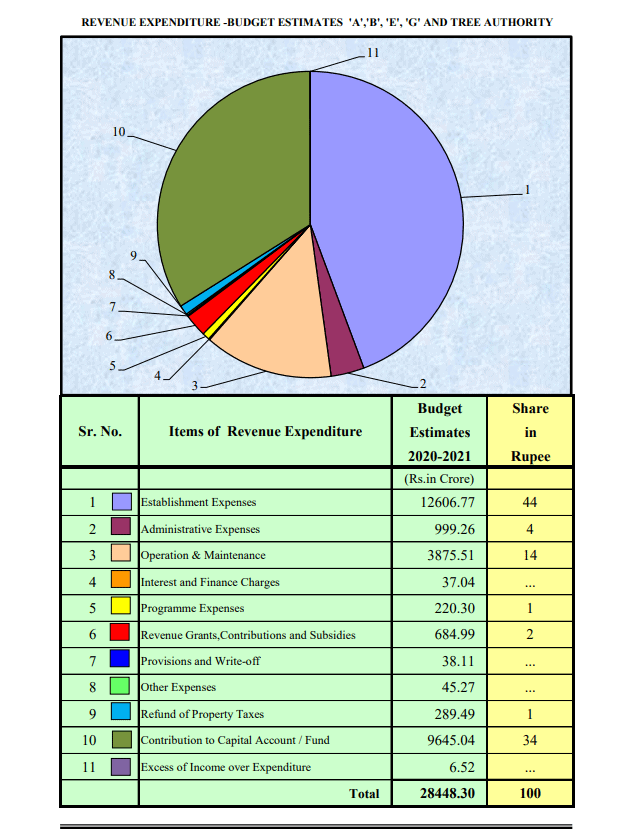

Towards the end of the document, there’s a graphical representation of income and revenue sources for quick understanding. This provides a clearer picture of how BMC earns and spends:

The representation shows that BMC expects its highest expenditure after the General Budget to be on Water Supply & Sewerage Disposal followed by Health and Pension Fund, Education, Slum Improvement and Improvement Schemes.

Since Octroi has been srapped, BMC’s income estimates show that its earnings remains dependent on state grants, followed by Property Tax and Receipts from Development Plan Department.

Of its Rs 28,448 crore revenue income, BMC’s revenue expenditure is mostly spent on establishment expenses, such as salaries, and operations and maintenance.

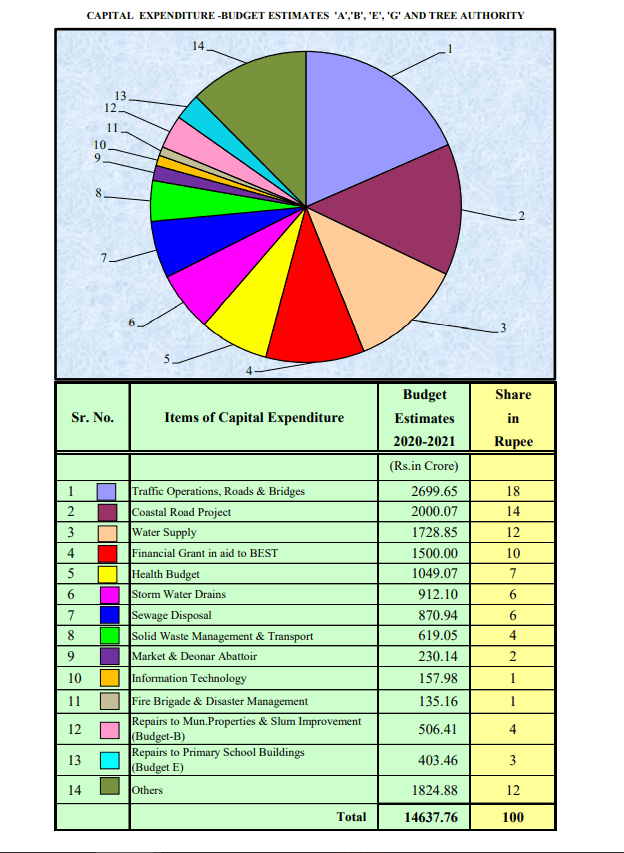

It’s the capital revenue that pays for services citizens associate with BMC such as storm water drains, solid waste management, water supply, among others.

BMC’s Capital Expenditure Estimates show that after Traffic Operations, Roads and Bridges, it expected to spend the most money – Rs 2,000 crore – on the Coastal Road Project in 2020-21. But BMC’s infrastructural push along its coast comes with severe environmental and social justice challenges.

Problems with the budget

The BMC budget attracts two kinds of criticisms: one is that departments such as health and education don’t get the necessary funding, and that the funding that’s made available is not utilised sufficiently.

Praja, a city-based NGO, argues that either the “civic body does not have the willingness and/or expertise to execute the spending, or that they are over ambitious to begin with and unnecessarily large provisions are made to please citizens and elected representatives with the size”.

It does not take accounting or civil engineering expertise to understand that if Rs 2,700 crore is earmarked for Mumbai’s roads and bridges, why is the problem of potholes still persistent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the gaps in BMC’s healthcare funding. An examination of BMC’s recent budgets by the Observer Research Foundation found that “there were minor changes in revenue and capital expenditures related to public health facilities”. The report notes that despite an increase in the demand for facilities since 2018-19, “almost the

same percentage of financing has been allotted, leading to severe shortfalls in provision (as exposed during the COVID-19 crisis)”. From 2014-15 to 2016-17, around 34% of the Health budget remained unutilised, according to Praja. Other departments are similar. Despite Mumbai’s annual flooding crisis, “48% of Budget Estimates of the Storm Water Drainage budget” was unutilised in 2015-16.

Last year, BMC significantly increased its education budget from Rs 2,733 crore the previous year to Rs 2,944.59 crore. But enrollment in BMC schools has been falling. 257 BMC schools have shut down in the last decade until 2018-19, including 41 in 2019-20, according to Praja.

Read more: Mapping floods: is Mumbai at the risk of being submerged?

No citizen feedback

A well-known antidote to the traditional form of budgeting is the idea of participatory budgeting which empowers citizens to deliberate and discuss civic works and public expenditure. The Pune Municipal Corporation invites suggestions from citizens on civic works they would like to see included in the budget. Citizens can fill an online form to submit their suggestions. Both the citizens’ response to participatory budgeting and the municipal corporation’s sanction of funds has been increasing over the past few years.

There is no participatory budgeting in Mumbai and no simplified and accessible provisions to nudge people to take ownership of their neighbourhoods and demand improvements.

*All charts from BMC’s budget document.

Also read: