What started off as a holiday in the Andamans for educators Supriya Singh and Katarina Roncevic, has turned into a two-country project to train teachers, students and parents on global sustainability goals. Using their expertise in “education for sustainable development”, Singh and Roncevic’s project The Turquoise Change is using education to tackle environmental problems on the islands of Havelock in India (Andaman and Nicobar Islands) and Zanzibar in Tanzania.

Like the Turquoise Change, there is a growing crop of environmental educators who have traversed the world of environmental activism, policy and new technology and eventually found their calling in education. More specifically, in bringing together all the associated knowledge and using education as a holistic tool to further their goal to protect the environment.

But can environment education save the earth?

“Education can play a major part in the required transformation into more environmentally sustainable societies, in concert with initiatives from government, civil society and the private sector,” said a 2016 UNESCO report titled Education for people and planet,which pushes for education as one of the tools for dealing with the environmental crisis caused by human behaviour. The report said, “Education shapes values and perspectives. It also contributes to the development of skills, concepts and tools that can be used to reduce or stop unsustainable practices.”

In India, traditional knowledge passed on within communities and informal nature education are common learning approaches. However, on the formal education front, India has an active policy for environment education. Environment education was made a compulsory subject in school curricula following a 2003 Supreme Court judgement, one of few countries to have the highest court weigh in on the importance of environment education.

How do you teach someone to protect the environment?

Through a pilot workshop on the Havelock island, the Turquoise Change aimed to make the connection between education and environment protection. Their goal is to build the capabilities of schools – students, teachers and principals as well as the local communities, youth and local NGOs to work towards the preservation, comprehension and celebration of the local environment.

Both Singh and Ronacevic are part of the multi-country Education for Sustainable Development network and felt that advancing sustainable thinking and lifestyles in schools on islands was important to support the small communities that live there in coexistence with nature.

In their first pilot phase (2017-18) they reached out to 50 teachers and 950 students and youth in Havelock.

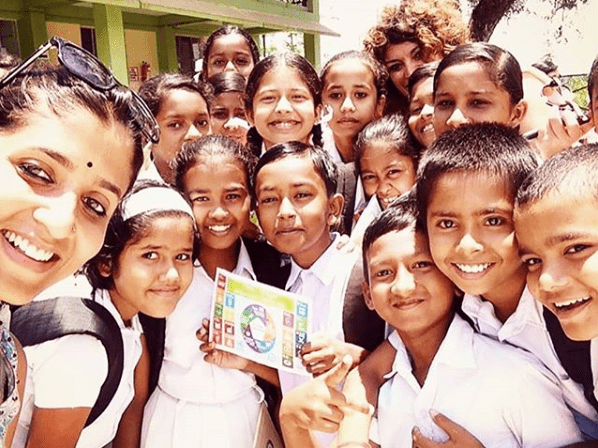

The Turquoise Change aims at supporting schools on islands like Havelock in the Andamans, taking into consideration their unique and local needs and training them to become changemakers and create “Islands for Sustainability”. Photo from The Turquoise Change.

“Students felt very strongly about human development issues like education and health care. But not so much on environment,” said Singh about their experience with students in Havelock. “They could not see the connect between their lives and the immediate environment.”

Connectivity is one of the main challenges faced by learners in Havelock, said Singh. “Connectivity impacts people. They feel disconnected from the country geographically, there is bad phone network, bad internet and a disconnect from what the world is talking about. You learn to live with it but get frustrated with the disconnection.”

Meanwhile, on the opposite spectrum, in the bustling, hyperconnected city of Mumbai, environmentalists and educators are working to introduce environment education in an urban context in city schools.

The Upcycler’s Lab is working on a game-based approach towards environment education in city schools. Using household waste, the lab creates board games and activities that educate children about the environment, wildlife and waste management. The games complement the Indian environmental studies syllabus.

Founder Amishi Parasrampuria originally started with creating upcycled products for adults. But after some years into it, realised that the scope for a conversation among adults, to change their mindset around waste and its impact on the environment, is limited. She soon realised that working with children is perhaps the way to go and decided to approach the issue of environmental protection the other way round – get children to influence change in adults.

The Upcycler’s Lab targets urban, high income schools mainly on issues related to urban waste management. “We focus on consumption and production and we primarily work with these students because they are the ones who are most likely to consume the most. It is a misconception that waste is the responsibility of ragpickers. We teach these students to be responsible for their own waste,” said Parasrampuria.

Upcycler’s Lab uses a game-based approach, complementing the school syllabus, to establish linkages between consumption, waste and individual responsibility. Photo from Upcycler’s Lab.

Mumbai-based environmental activist Rishi Aggarwal believes that actionable tasks can make students more aware about their linkages to the environment. With this in mind, he has started to engage with young learners through an initiative called the Safai Bank of India.

The Safai Bank emerged as a response to the plastic ban in Maharashtra. It creates a banking system for students where their schools and colleges open “accounts” to deposit multi-laminated plastic packaging (like chips packets) which are then treated as per waste management rules. “Withdrawal” from the accounts is in the form of tokens and rewards depending on the deposit amount.

Using an everyday concept like banking, the organisation aims to raise awareness among students on plastic waste management and being responsible citizens, while diverting multi-laminated waste items away from dumping grounds. So far, Safai Bank has collected over 3000 waste items and has close to a 100 active “account holders” since its launch on World Environment Day this June.

Catch them young!

While most initiatives for children target middle school students, the Centre for Environment Education has taken it a step further and targeted pre-schoolers. The centre of excellence supported by India’s environment ministry, recently launched The Planet pre-school on World Environment Day in June this year to provide a “nature-based early learning programme.” The pre-school believes that “experiencing and learning about the environment in early childhood builds a foundation for lifelong environmental literacy.”

And while pre-schoolers are already getting a headstart with environment education, technology has also democratised environment education, requiring no classroom, location, age or financial eligibility to learn about the environment. The SDG Academy, an online education initiative of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, emerged as a way to help train the next generation of sustainable development practitioners. It has had over 180,000 enrollments over four years, primarily from adult learners in the 24-35 age group, from 180 countries, including India.

The courses, many focusing on the planet and climate change, are designed to fill the gap of high quality educational content on the Sustainable Development Goals that were adopted by countries across the world three years ago in September 2015. Similarly, the World Wildlife Fund in India has a digital academy for environment education among children as well educators.

Environment leaders or ecotourists?

Both Singh of Turquoise Change and Parasrampuria of Upcycler’s Lab are upbeat about the fact that environment is finding its space in education and expect to see a positive result in the students that they have been working with.

Chandrika Bahadur, director of the SDG Academy and president, SDSN Association, added that there is no doubt that an educated, aware population that is sensitised to its planetary footprint will be better equipped and more disposed to addressing the problems of the planet.

“There is growing evidence to show that globally, the Millennials are much more tuned to environmental issues as compared to older populations precisely because of the education they have received,” she said.

Aggarwal however, is not convinced about the impact of education on environment protection.

“At least one lakh students in the 90s, have gone through the city’s many nature education programs run by naturalists and environmental groups. If nature education was successful, we should have had at least a chunk of those students now working in environmental conservation. But that’s not the case. Those programs have just produced more eco-tourists,” said the environment activist, adding that naturalists may train children to become nature lovers but does not equip them to become environment leaders or have any impact at the policy level.

Aggarwal became involved with the environment as an adolescent and almost 30 years into activism, he feels that the scenario for environment and conservation in India is bleak. “Where are the environment leaders that all these years of environment education should have generated?” he asks. He believes that for environment education to be impactful, it has to include elements of activism, governance, communication to navigate bureacracy and the complexity of policy making.

Reflecting Aggarwal’s scepticism around environment education creating “ecotourists” rather than “environmental leaders”, educator Shaurya Rahul Narlanka wrote in an article for Research Matters last year, about how environment science education is failing its students.

“With the primary focus on dispensing a collection of facts and figures about the environment, and prescribing oversimplified solutions to overgeneralised problems like portraying deforestation as bad and planting trees as good, the environmental science education in this country falls short in meeting its ultimate goal — making students really aware of the single biggest issue of our time and inspire them to work towards it,” wrote Narlanka.

He stressed on the need for helping students understand their personal stake in the problem to genuinely have an impact. As these students grow up to be voting citizens who can make an impact, a shallow understanding of the problem could lead to supporting shallow policies. “By not understanding their personal equation to the problem, they fail to internalize the gravity of the issue and therefore, lose the ability to relate to the need to solve that problem and, even ignore it when it feels inconvenient,” he wrote.

Learning approaches and impact

Environment education in India was made compulsory in formal education through a Supreme Court ruling in 2003. The ruling has resulted in over 300 million students in 1.3 million schools receiving some environmental education training, according to a UNESCO study.

Most educators however push for an integrated approach that uses the strengths of the curriculum and combines it with other educational tools.

The Upcycler’s Lab board games are based on school curriculum and founder Parasrampuria has found a positive response to the integrated approach. She feels that there is an improvement in the entire ecosystem of environment education. “It is surprising how much more awareness there is. Environment education is part of the school curriculum as a subject and not blended with geography or civics or some other subject. The teachers are putting in a lot of effort. Public policy changes have made the topic of waste management and environment more accessible. Ten years olds are so aware – they are asking questions about manufacturer responsibility in waste management,” she said.

Bahadur of the SDG Academy adds that a blend of knowledge, analytical skills and social and interpersonal skills together can help create future environment leaders.

The UNESCO report on Education for People and Planet too recommends a multi-pronged approach towards learning which brings together formal education, traditional knowledge-sharing through community and learning through work and daily life, the latter two already common practices in India on account of cultural traditions.

The Nature Science Initiative in Dehradun for example believes that the earth itself is the great educator. Its programmes in the field have turned school dropouts like Taukeer Alam into a field researcher assistant.

Educator Narlanka vouches for experiential learning in his Research Matters article, writing, “Facts are easy to ignore, but experiences are not. We need to heed to this wisdom and revamp our environmental classes to become more personal and experiential to encourage students to find more personal reasons to conserve their environment and progress the country’s environmental efforts in a comprehensive and fruitful manner.”

But can experiential learning have any real impact? Or is it, like Mumbai activist Aggarwal said, an opportunity to just to create general nature lovers and “an excuse to buy new gear”?

Experiential and community based learning infact could work better in the current scenario where challenges to formal education are many. According to a 2016 Global Education Monitoring Report (GEM Report), the world is lagging behind in its education commitments and while India has achieved “universal primary enrollment with an adjusted net enrollment rate of 98 percent, it has the second-highest number of children out of school among countries with data”.

Additionally, with the growth of technology for learning, the absolute reliance on formal education is seeing a shift.

“The most exciting and innovative development is how young people are teaching themselves — using social media to access content such as ours and creating opportunities to peer learn and create awareness on these issues,” said Bahadur of the SDG Academy.

“We are still in the very early stages of educating our young people on sustainable development. I am deeply optimistic that teaching sustainable development in smart, innovative and fun ways will have a huge effect on the attitudes and aspirations of young people in India and the world and that this young generation will push us all to a more sustainable future.”

[This article was first published in Mongabay India and has been republished with permission, with changes in headlines only. The original article may be read here.]