As this article gets ready for publication, we already know of 24 fatalities caused by relentless rainfall and flash floods in Himachal Pradesh and other parts of north India. Several deaths have been reported from the capital Shimla itself, while hundreds remain stranded in various other parts of the Himalayan state. However, this is not the first extreme weather event to befall the region in recent times, nor, unfortunately, does there seem to be much hope of such disasters being stemmed. Will the allocation of some extra funds in the name of green bonus and the setting up of a separate ministry dealing with development be enough to tackle the emerging serious environmental challenges in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR)?

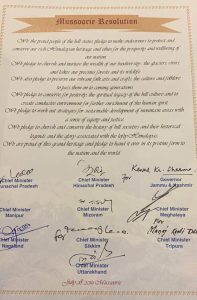

At a Himalayan Conclave in Mussoorie on July 28th, representatives from 11 Himalayan states along with Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, deliberated on the development issues confronting the Himalayan states. Pic: Rishabh Shrivastava

At a Himalayan Conclave in Mussoorie on July 28th, representatives from 11 Himalayan states — all the north eastern states, Kashmir (still a state then), Himachal and Uttarakhand — along with Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, deliberated on the development issues confronting the Himalayan states and ended up signing a ‘Mussoorie Resolution’ – pledging to protect and conserve the environment and culture of the region. Officials from Niti Aayog and the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation also participated in the conclave. The states unanimously agreed to pursue two reforms: allocation of a ‘Green Bonus’ to Himalayan states and setting up of a separate ministry dealing with the Himalayan development.

The conclave was of significance given the rapid urbanisation in many parts of the IHR. Himalayan cities and towns grapple with the same set of challenges like other major metropolitan cities – water shortage, traffic issues and parking woes – to name a few. But given the difficult and unique geographical setting, these challenges become more complex and significant in this area which needs to be addressed by the government and citizenry at large. The added burden on the fragile Himalayan ecosystem due to the surge in tourism to these areas makes the situation worse.

But isn’t urbanisation inevitable?

Urbanisation in itself is not a problem. As per UN estimates, by 2030, more than 400 million Indians will be living in cities. But urbanisation, if executed in a haphazard, unsystematic and unplanned manner can be a potential hazard for the environment, human life and property. Keeping in mind the fragility and sensitivity of the Himalayan ecosystem, setting a sustainable agenda of urbanization becomes critical.

As per the 2011 census, Uttarakhand registered the largest number of notified towns while Mizoram registered the highest proportion of urban population in the IHR. As per a study published in the Journal of Urban and Regional Studies on Contemporary India, Uttarakhand registered an urban growth of almost 56.38% from 1971 to 1981. From 2001 to 2011, the state witnessed an urbanization rate of 10%. From 1901 to 2011, the proportion of urban population living in the state has risen by almost 20 times, which is extremely significant for a Himalayan state. Such rapid rate of urbanization, in an unplanned and unsystematic manner, creates additional burden on existing resources and infrastructure. Based in difficult geographical conditions, such a burden can result in negative alterations of the mountain ecology.

Apart from cities in the plains of Uttarakhand like Udham Singh Nagar, Dehradun and Haridwar, several towns and cities have developed in the hills like Srinagar, Tehri, Kashipur etc. These have evolved into semi-urban areas as they provide decent employment opportunities, education services and better exposure to the outside world as compared to a deserted village in a remote hill district or location.

As more and more people continue to flock to these towns, unplanned urbanization has been on the rise, resulting in a rapid rise of concrete structures, quantity of waste generated, deteriorating air quality, severe water shortage, rampant traffic jams, reduced green cover and other issues. The way this urbanization in happening is challenging the very idea of peaceful, pristine and ecologically sensitive mountains. As a result, these regions are becoming more susceptible to natural disasters (landslides, slope failures, flash floods etc.) and climate change.

Troubling trends in tourism

One major reason behind such environmental degradation is that we have been made to fall in love with the wrong idea of tourism and travelling. While tourism in mountains is being promoted extensively in advertisements and travel blogs, the people and the government have failed to understand and highlight the fact that there is something extremely wrong with the present day trend of vacations in a hill station or a visit to a fully equipped, lavish homestay at an interior village situated in the hills. Instead of maintaining the natural beauty of these spots, there has been a systemic effort to equip these places with modern technology and services, encouraging more and more tourists to visit.

While this has generated increased income for the state and other stakeholders of the tourism industry, the dumping of packaged water bottles, snacks and other waste, motorable roads inside jungles, and music parties on the meadows has resulted in irreversible impact on the hill ecosystem. For instance, excessive bike rides has reportedly caused the environment to deteriorate significantly in Ladakh. The Nepal government recently initiated the highest clean up in the world at Mount Everest peak. The recent wedding event organized by the South African millionaire Gupta Brothers in Uttarakhand’s Auli ended up polluting the soil and water streams. Mussoorie has been rotting with increased garbage dumping as it has zero facility to treat and recycle its waste. Yet, the hill towns and cities are witnessing a steep rise in construction of new hotels, lodges, cafes and restaurants.

Nefarious connections

Despite numerous rulings by various judicial forums, Himalayan cities and towns continue to develop in a haphazard manner. Last year in May, an Assistant Town Planner was shot dead by a hotelier because of a Supreme Court order regarding demolition of unauthorized structures in Kasauli. The NGT in the landmark case of Yogindra Mohan Sengupta v. Union of India in 2017, had noted:

“…the unplanned and indiscriminate development in the Core, Non-core, Green and Rural areas in Shimla Planning Area has given rise to serious environmental and ecological concerns…It has come on record that there are inadequate facilities in relation to water supplies, sewage treatment, collection and segregation of different kind of wastes.”

The case went on to highlight the poor functioning of the administrative system in allowing construction of illegal structures. The green court also issued a set of guidelines with a view to ensure environmental conservation in one of the oldest and most prominent hill stations of India, Shimla.

Rethinking development

Given these facts, more than the budget and a separate ministry, state governments of the Indian Himalayan Region need to devise a sustainable policy on tourism and infrastructure creation. Independent working groups and task forces can be constituted to carry out surprise audits in the sensitive zones and defaulters should be prosecuted under criminal law with strict punishment. Along with the defaulters, state agencies responsible for implementing bye laws, building codes and master plan norms with respect to illegal structures must be booked for their negligence and inability to discharge their statutory duties. Politicians must take on issues concerning urban development and environmental sustainability without succumbing to pressure from the real estate lobby.

It is imperative for all of us to understand that we are chasing the wrong model of development and economic growth. One which is neither inclusive nor sustainable. The Himalayan region in particular is prone to multi-dimensional threats, which requires a pragmatic and comprehensive strategy for mitigating the risks. This will not only ensure stable growth of the region but will also respect the lives of those who are completely dependent on the hills for their livelihood.

Promoting controlled and responsible tourism would be a good place to start in order to preserve the ecological identity of the mountains.