Bengaluru is now increasingly witnessing the combined effects of climate change and rapid urbanisation in varied forms. Be it the heat island effect, or increased intensity of rainfall over a shorter duration of time, flooding different city areas.

Yet, climate responsive strategies largely remain obscured in developmental strategies as well as governance models.

Impact on informal settlements

The harshest brunt of this situation is borne by people living in informal settlements across Bengaluru. The city has almost 2000+ slums spread across, with only 25% of these slums having access to some basic services.

These settlements are constructed using heat-absorbing materials like tin, asbestos, tarpaulin etc. which causes the heat to remain trapped indoors. Homes in these settlements also do not have any ventilation, except for their front doors.

Due to a lack of resources the priorities of residents in these settlements do not include climate change, adaptation and mitigation strategies, precisely because their immediate needs remain unaddressed. Additionally, climate change remains an abstraction for them, which provides no immediate monetary or service-based incentive.

How then to make residents be active participants in the agenda of climate change? This was the vantage point of our climate pilot. The idea was to turn climate change into a tangible concept for these communities, working upon which they can also gain monetary and other benefits in the long run.

Read more: Bengaluru: Still unprepared to face unusual weather events due to climate change

Climate pilot

Palaniamma has been living with her husband and son in a 2-room semi-pucca house in Janakiram Layout for the last 15 years. She and her husband are sugar cane juice sellers. Their son is a daily wage construction worker.

The whole settlement of Janakiram Layout is located on Railway land and the settlers own a “Parichay Patra” that says they have been living in the area for a long time. They do not have access to legal electricity connections and rely completely on illegal connections from nearby electrical posts.

Palaniamma’s home is a typical slum dwelling. It is congested, with a leaky asbestos roof, and no ventilation except the front door. Due to sudden and frequent electricity cuts and voltage fluctuations, she has had to change damaged appliances like TV, fridge, etc. multiple times.

Mahila Housing Trust (MHT) is a grassroots, socio-technical organisation that works to strengthen the collectives of women in the urban informal sector and advocate action on improving housing living and working environments. MHT, in collaboration with SELCO Foundation–which seeks to inspire and implement socially, financially and environmentally inclusive solutions by improving access to sustainable energy)–implemented a climate pilot in Janakiram Layout in Bengaluru.

About the Demonstration Pilot

The pilot included the installation of a solar home lighting system to remove dependence on illegal grid connections. This involved designing a roofing mechanism, which consisted of:

- Solar reflective white paint over the existing roofing sheet and

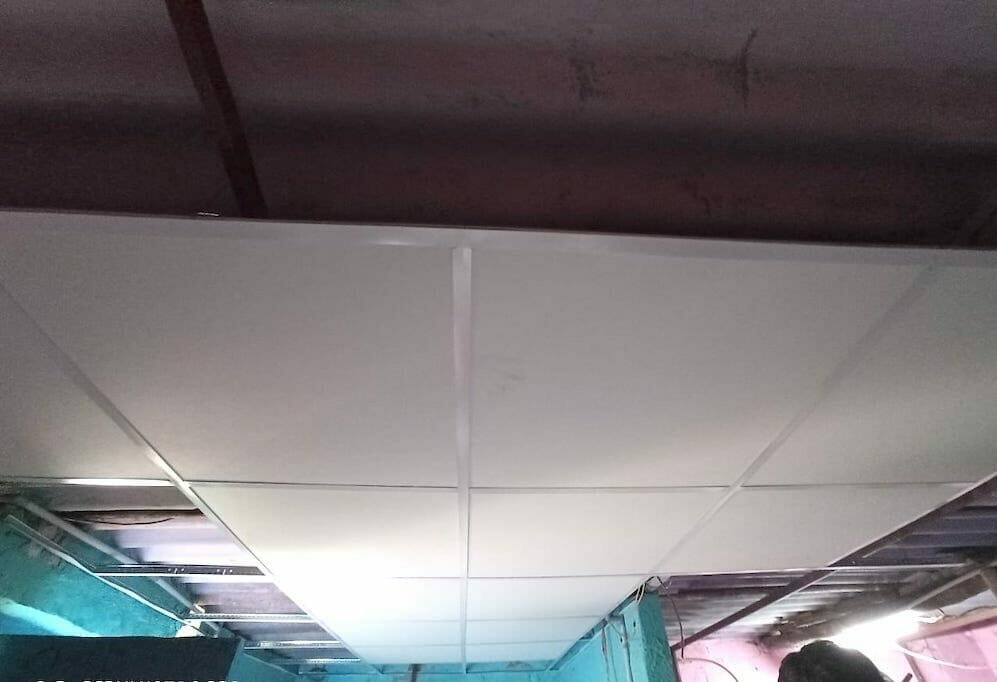

- A water and fire-resistant false ceiling with a 45mm gap was also installed inside the house

The combination of both these technologies was to reduce indoor temperatures by 2-3℃. It will also prevent any water leakages from the roof.

The solar home lighting system is currently supporting the entire energy requirement of Palaniamma’s household, including all the appliances that she requires for her day-to-day usage. If she had a legal electricity connection, she would incur a bill of at least Rs 450-500 per month for electricity usage.

Post the technological interventions, Palaniamma admits happily that there was absolutely no leakage from the roof even during very heavy rains. Her thermal discomfort has reduced to a great extent as well. With the solar energy system in place, she had uninterrupted access to electricity, unlike other houses in the neighbourhood, which faced power cuts. Another added benefit is that her house now has a greater aesthetic value. She has received a lot of compliments on how beautiful her new roof looks.

The pilot installation has led to reduced temperatures in Palaniamma’s house vis-à-vis other houses in the slum, according to our initial records. We will track the performance of this pilot over the course of a few months. The pilot has seen effective reduction in temperatures during the summers (between 2-5 degrees) and due to solarisation, she incurs less cost on electricity. Also, the house doesn’t frequent power cuts.

Read more: How Bengaluru youth are taking part in the global movement against climate change

Participation in the Climate Change Agenda

We had envisioned utilising this pilot as a tool for engaging communities in the climate change agenda, which is a fairly abstract concept for them. The pilot has led to an emerging curiosity and dialogue around the issue of climate change within the settlement. Women are now also eager to know more about renewable energy installations for their own homes, customised as per their own needs. Palaniamma was also invited as one of our speakers during the City Resource Forum (CRF) meeting and she talked about the benefits of the pilot.

This intervention has enabled MHT to mobilise women, form a community action group (CAG), and provide formal training on climate change. The training provides insights on the intersection of climate change, urban governance, and public participation.

MHT’s ultimate goal is to empower the CAG members and encourage them to become active participants in the climate change agenda at the city level through avenues like the Citizen resource forum “Ellara Bengaluru”, and ward meetings.