I have been pursuing a master’s degree in Sustainability in Helsinki for the past year and a half. Scouting for a thesis topic along with my interest in the intersection of water, communication and education brought me right back to Bangalore where I had studied and worked earlier in the areas mentioned above. This time, I was trying to look at how design interventions can enable public awareness and participation in the functioning of a sustainable urban water management system. My research was based around the Jakkur Lake — and this was for a specific reason.

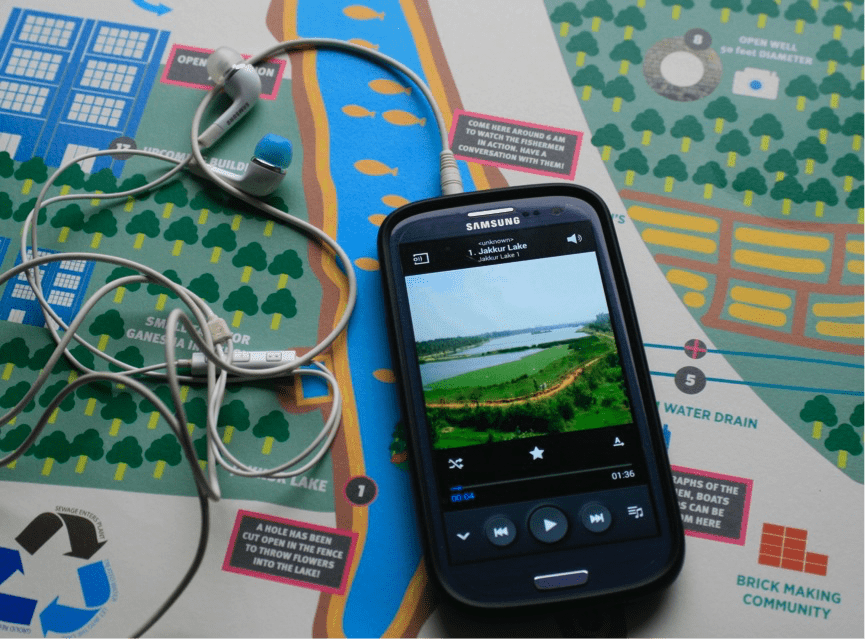

View of the Jakkur Lake from its northern tip

Bangalore and water

Bangalore was once called the city of a thousand lakes but over time, it lost most of them to urbanization, sewage dumping and encroachment. In 1960, there were approximately 282 lakes while today; barely 34 remain in their full glory. The city has lost more than one lake a year to the growing demands of humanity.

During a discussion, water expert S Vishwanath stated that the current key challenge that Bangalore has in terms of sustainability is water management. The main reason is because it has only one reliable source—the Cauvery River that is over a 100 kilometers south of the city. There is a limit to the amount of water that can be drawn from the Cauvery due to the inter-state political activities and agreements between the state and the farmers. Besides the Cauvery, the only resources that Bangalore can fall back on for fresh water is its lakes and ever-sought-after groundwater.

As mentioned earlier, even these lakes, wells and other water bodies are fast disappearing and most of them are filled with sewage and garbage. Worsening the situation is the depletion of groundwater. Given the current state, why don’t we look at a well functioning system that exists within the city that could be a potential model for water sustainability?

What makes the Jakkur Lake so special?

The Jakkur Lake is in the north-eastern part of the city and is one of the largest and cleanest water bodies in Bangalore. It is the main lake in the chain of lakes comprising of the Yelahanka Lake upstream and the Rachenahalli Lake downstream. It is about 140 acres large and has recently been rejuvenated by the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA).

Besides being a freshwater lake that provides water to the city, it is particularly special because it is a potential model for Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM). This unique socio-ecological ecosystem highlights the symbiotic relationship between nature and humankind. By serendipity, a sewage treatment plant (STP) with a capacity to treat 10 million litres a day was set up north of the lake by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). This treatment plant receives wastewater from about 12,500 households from areas around Jakkur like Yelahanka. The plant is currently able to let out 8 million litres of treated water into the man-made wetland that further purifies the water by a natural process before letting it enter the lake.

Therefore the lake is fed with 8 million litres of treated water everyday, which in turn recharges the ground, increases the water table and fills up the bore-wells and the beautiful old open wells — heritage structures that adorn this area and are in need of preservation.

The constant water inflow has helped the lake become a hotspot for biodiversity of all sorts. It also ensures that the lake is always full, thus providing potable water to the communities who use the wells around the area. This is what makes the system so special. By this fantastical process, raw sewage is transformed into potable water, whose origins even the communities dependent on it, is unaware of.

The 10 MLD Sewage Treatment Plant at the north of the Lake

Along with the above stated benefits the lake also provides services and livelihood opportunities. There is a family that lives by the lakeside and makes bricks for a living. All the water that is needed for this process comes from the bore-well that is fed by the lake. People from settlements nearby use the lake to have a bath as well as wash their clothes and utensils. The small tank built for Ganesha immersion, in a well thought out manner, is separated from the lake by a net, so that debris and flowers can be collected before the same pollutes the lake.

The biggest cohort that is highly dependent on the lake for their livelihood are the fishermen. On a normal day, they are able to collect at least 100 kilograms of various kinds of fish and during peak season up to 500 kilograms. The fish are fresh and some are still breathing as they are casually tossed out of the net onto the ground, to be measured and sold to clients who have already lined up for their share.

Now, with the STP, the fishermen, the communities using the wells, the birds that flock every morning and the design of the lake itself, there are multiple well functioning systems linked to the same entity—the Jakkur Lake. Every stakeholder, including the big decision makers are somewhat aware of the various individual parts of the system but are not entirely informed about how it functions at the macro level. There is lack of communication about the same and the importance of the various involved stakeholders is not realized.

How do we create a zoomed out picture of this closed-loop system? How do we inform the higher authorities about the positive impacts of such a model and get them to act upon it, maybe eventually enabling systemic change? How do we take a step forward in creating a more water sensitive city and how do we bring out all the quirky and interesting stories of the individuals and communities around this lake to enable a sense of ownership? This cannot happen without public involvement and participation.

A possible method to communicate this idea

Keeping the above questions in mind, I designed an ‘experiential’ audio-visual walk. It uses the lake as an exhibition walk-through that allows people to experience the space for what it is. A map and an audio guide help the audience unravel facts, narratives and offbeat aspects of entities around the lake while involving the locals in the process and increasing awareness in an engaging manner.

The map contains two levels of information — one for the people who are interested in the stories and another for the more technical facts and figures. This can be used as a communication tool for any anyone interested in learning about, or working around this lake, starting from students and leading to the decision makers who have immense clout. I had the opportunity to take 30 students who study sustainability at the Bhoomi college in Bangalore on this walk. They were very excited about it and had a lot of questions and ideas on how to take it forward.

The map and the podcasts are available online. Print a copy of the map and carry the sound files in your cellphone. Try the walk with your friends and family. Let’s get a dialogue going about how a closed-loop system like this can be appropriated to other lakes in the city, helping Bangalore with its current water scenario.

To download the map or know more about the project, please visit: https://jakkurlake.jux.com

Do write in, if you have any comments, questions or feedback!

What would be the cost to setup an STP like this? Horamavu in North Bangalore has a 50 acre named Horamavu Agara Lake and there is land allocated for an STP close to the lake. Horamavu has no sewage system and most of it is lifted by Honey Suckers. A small amount of sewage from nearby apartments and layouts directly reach the lake. BBMP has no funds, and so nothing happens. The lake is dying, the water table is sinking and apartments spent a lot every month on honey suckers. I am sure if the RWAs of Horamavu come together, there will be enough funds to build and maintain an STP at fraction the cost of what each resident or apartment incurs. Can anyone shed light on how much will it cost to setup and maintain and STP like the one at Jakkur?

STP can cost anywhere between 1.5 Cr to 2 Cr per MLD. Horamavu lake would require about 5 MLD plant. So expected capital investment is Rs. 7.5 to 10 Cr. Operational cost would for this 5 MLD plant should be somewhere between Rs. 20 to 25 Lakhs per month.

Thank you Sachin. That was a very informative. Are there cases in Bangalore or elsewhere where STPs are built and managed through public participation? One of the major areas of concern is how STPs are never maintained after spending crores to build them. A 20 MLD STP was planned by BWSSB in Horamavu Agara sometime 2011 at a cost of 22 Crs. It has never seen the light of the day. Check this article http://savehoramavulake.blogspot.in/2014/02/stp-plant-in-horamavu-agara.html

good work! https://jakkurlake.jux.com/ creates a good picture of lake. btw under which govt. body does this lake comes (u mentioned BDA above, isnt it LDA?)?

Actually we (saytrees.org) are planning to plan trees about this lake so need to see from where to take permissions etc… do we need to take permission from jakkur airfield authorities?

do u have any such info?

Anyways, kudos for the good work done.

Brilliant Job Aajwanthi Baradwaj! Chander Shekhar rana the Jakkur lake is developed by BDA but will be handed over to BBMP for maintennace. If you are anytime interested in working with the Jakkur Lake you can join our group JalaPoshan -https://www.facebook.com/groups/JAKKURLAKE/

Hi, I am a regular visitor to this lake for last 9 years. I know the condition then and now. Definitely there is improvement at snail’s pace. Also they are making a park in the banks of this lake. Good. Not fenced, not written any dos and don’ts. But, I want to have at least one part of this park to be reserved for some games for boys and one part to be reserved for Pets. Why is that we are not thinking about them while making parks? Frankly, I have no Idea whom to write about such requirements and the need of having such facility at least one in this area. Can somebody help me with right contacts?