This monsoon, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) plans to help Mumbaikars brace themselves for days of heavy rain through a disaster management app. Accurate information and warnings are of utmost importance at such times, as they can help people make better decisions about their safety.

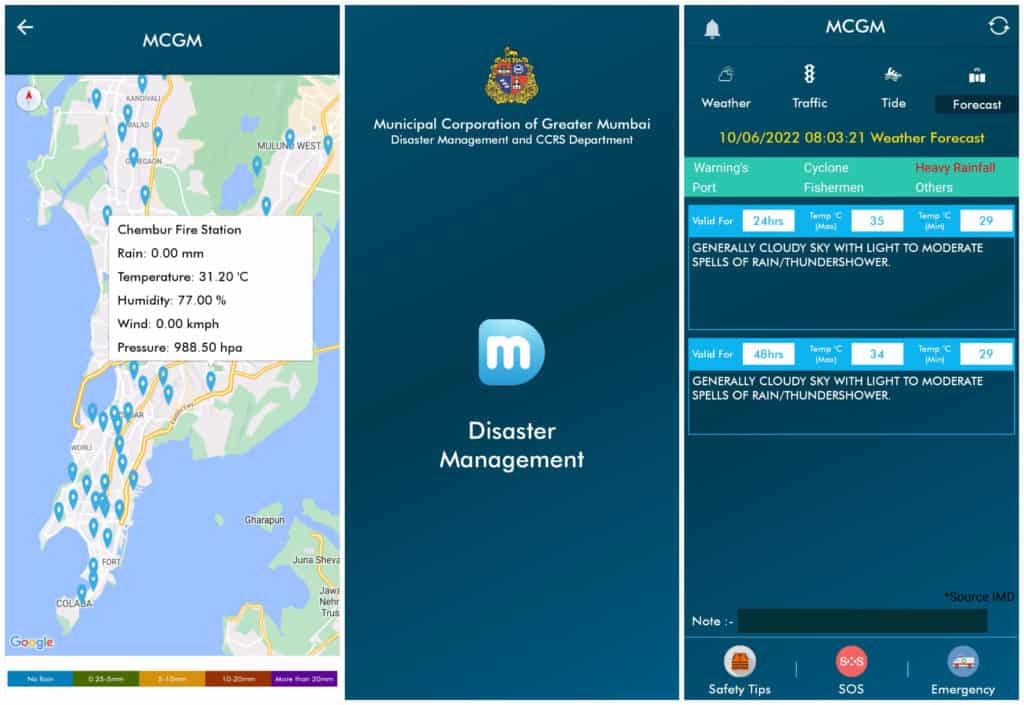

The mobile application Disaster Management BMC, available on both iOS and Android, will be relaunched to keep citizens informed about the state of monsoon. It was first launched in 2016 but failed to reach the masses. Through this app, areas likely to be waterlogged will be flagged anywhere between six to 72 hours in advance, along with the probable height of floodwater and location-specific risks.

“The app is still in development, but the updated version will be out in the next few days,” said Mahesh Narvekar, director of the BMC’s disaster management department.

This information will be given through iFLOWs – the Integrated Flood Warning System installed in the city in 2020. The system factors in the amount of rainfall, tide levels, topography, land use, drainage, population, and the level of water in the rivers. The 165 automatic rain gauges (ARG) installed by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), BMC and IMD will be used to collect rainfall data, said Narvekar.

The app currently gives weather data – temperature, wind, humidity and pressure – in 140 locations in the city. It also lists the forecast, tide levels and traffic diversions, marking emergency contacts of police stations, fire stations, hospitals and ward offices on the map. Additionally, it has a repository of safety videos, the function to send an SOS call to emergency contacts and a direct link to the disaster management helpline, 1916.

Other apps that aid in disaster management

BMC’s Disaster Management app joins a host of other governmental mobile apps on weather available in India. Mausam, Damini, Meghdoot and UMANG were launched by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) to extend detailed weather information to mobile phone users. Mausam gives general weather updates and alerts, UMANG adds forecasting to other utility services, Damini is specifically for lightning, and Meghdoot is for farmers.

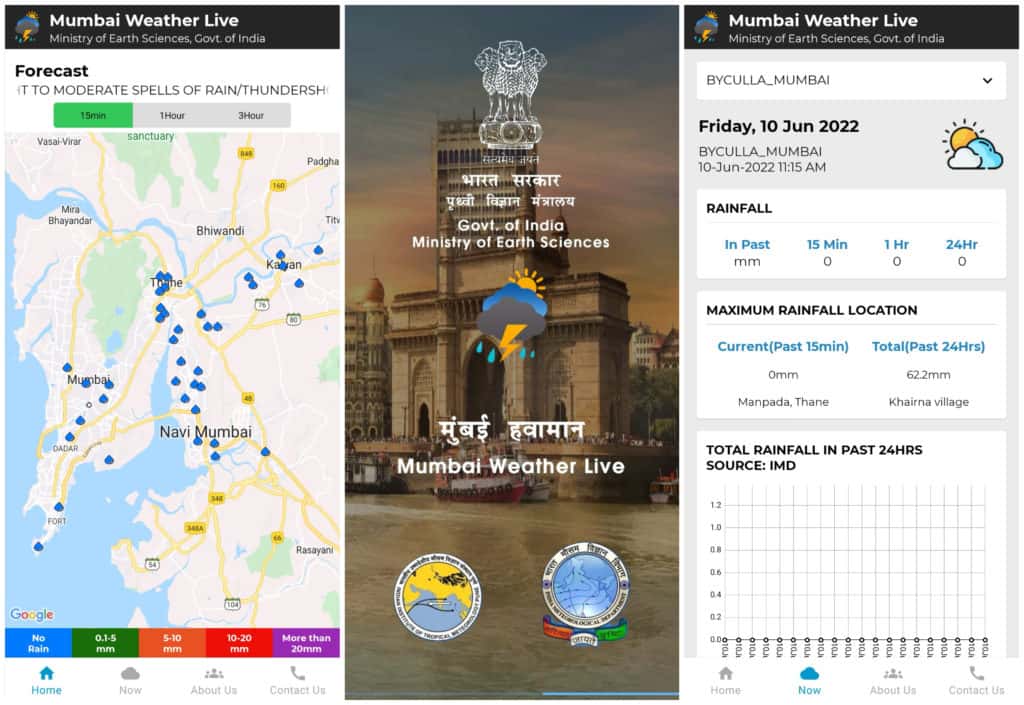

Adding to this mix in Mumbai is the Mumbai Weather Live app, a collaborative venture by IITM, IMD, BMC, Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC), and Central and Western railways. The app collates data from all the above agencies, providing location-specific updates about rainfall at 139 spots across Mumbai and Navi Mumbai. Its website includes satellite and radar imagery, helpful to understand cloud movement and precipitation and hence, forecasting.

The IMD’s weather information infrastructure consists of two main automatic weather systems (AWS), at Colaba and Santacruz, and 20 additional ones. The BMC has 60 of its own AWS, alongside the rain gauge network. “The BMC has a dedicated wireless communication system to which each ward and control room is connected. We monitor the levels of the rivers and dams to check for overflow and tide levels,” says Prabhat Rahangdale, former deputy municipal commissioner (disaster management).

Efficacy of the disaster management app

The BMC’s Disaster Management app, however, is not new. It was first launched in 2016, but not many people used it. One of the main factors was poor outreach efforts.

This is similar to other disaster management apps all over the country. When researchers from Keio University in Japan surveyed all 33 disaster-related apps available in India in 2018, they found people’s responses to be lukewarm. Limited outreach meant that participation was also limited. At the time, the BMC’s disaster management app had been downloaded only around 5,000 times.

“Undeniably, there has been a significant progress in technological aspects related to disaster monitoring and forecasting,” says the study. “However, knowledge generation and dissemination through these technologies remain to be constrained due to issues like limited mobility and coverage.”

That number has now doubled, surpassing the 10,000th download. And while this milestone is an improvement, the reach of the app lags far behind the platform that poses the biggest challenge to it: Twitter.

Weather enthusiasts, interested in tracking, analysing and predicting the weather are fairly popular on the social media platform. Some even have private AWS they use to track and share various weather parameters. The account @IndiaWeatherMan, unaffiliated with any official weather agency, has almost 90,000 followers.

“The app isn’t very popular,” says Aryan, who runs @MumbaiiWeather. “I rely on rain gauges for rainfall data, Google maps for traffic and official alerts on news and Twitter.”

The BMC’s own Twitter account boasts a following of over 7 lakh and is fairly regular in responding to complaint tweets. “It should be the IMD proactively alerting heavy rains and BMC alerting traffic and waterlogging. But if you look at BMC’s Twitter account, they hardly give updates. It’s mostly private bloggers who update regularly,” says Aryan.

Commuters depend on fellow Mumbaikars – and tweeters – who send in updates of flooding at their location, which others amplify. “I’ve seen it help a lot of people, especially when it’s done by accounts with a bigger reach,” says Aryan.

Read more: Climate change, rainfall patterns and what it means for Mumbai’s monsoon

Crowd-sourcing for real-time flood data

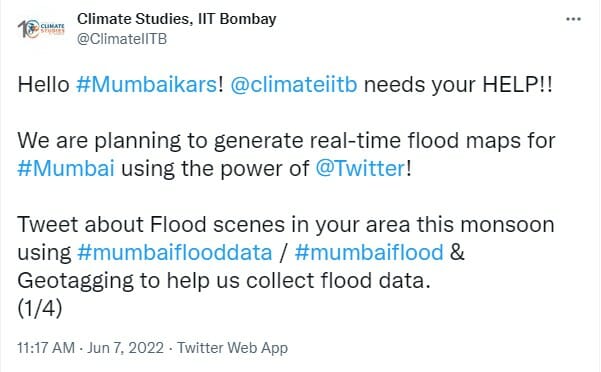

Volunteered tweets can do more than providing information to commuters who are stuck. The Climate Studies wing of IIT-B has embarked on a project to generate real-time flood maps of Mumbai, powered by Twitter. On June 7th, they put out a call for flood data, adding, “The flood maps will generate warnings based on real-time flood depth levels. They will be further extended to monitoring and experimental forecasting of #mumbaiflood.”

“The BMC does monitor the floods, but the levels aren’t available to common people,” says Subimal Ghosh, who heads the Climate Studies wing. “A huge number of Mumbaikars tweet daily, so if they see some flooding and tweet it with geo-tags and the hashtag #MumbaiFloodData, we will code it into a website portal. So, the real-time flood level data will be continuously updated.”

Subimal points out that the data given by the apps are forecasts, not the real-time level of water collected in an area. Getting citizen data, after checking for quality, will be helpful in validating the forecasts and flood models. This will be particularly helpful for iFLOWs, whose data has had a poor validation since its start.

While the project is currently on an experimental basis, it will be transferred to the BMC or IMD if successful.