In 2010, the United Nations declared access to clean drinking water as a human right. Yet, a large section of the Indian population suffers from the lack of it.

A 2017 report by WaterAid India, titled Wild Water: The State of the World’s Water, stated that around 63 million of India’s 833 million rural population has no access to clean drinking water. The larger problem, however, lies in the lack of equal access to clean and safe drinking water for all citizens in the country, especially the poor, in both rural and urban areas. Among the middle or higher income groups, this is manifest through increasing dependency on expensive packaged drinking water or unreliable, private sources.

Clearly, some things need to change. Seeking respite from the current situation, private enterprises and government bodies in a few cities are innovating on a possible solution – by making clean drinking water available through water ATMs. The national capital is one such.

The ‘what’ and ‘how’ of water ATMs

A water ATM is like a vending machine that provides clean drinking water 24 hours a day. It is powered by solar energy, integrated with reverse osmosis (RO) and ultra-filtration units with reduced operational costs.

It’s been four years since the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) started its pilot water ATM project in West Delhi’s Savda Ghevra, where users can withdraw water through these water ATMs using a smart Sarvajal card at 30 paise per litre. These machines were installed by Piramal Foundation, the philanthropic branch of Piramal Group.

Delhi Jal Board (DJB) is the primary provider of water supply services to citizens, including the poor and marginalised sections, within the National Capital Territory of Delhi. Due to unplanned and unauthorised growth of the city, a host of informal settlements including resettlement colonies, urban villages, rural villages, Jhuggi-Jhopdi clusters, and unauthorised colonies have sprung up. People residing in these areas do not have piped water supply. As one way to resolve the issue, DJB took up the initiative of providing safe drinking water to these informal settlements through water ATMs at an affordable price.

Potable water is arranged by the vendor through installation of an RO plant. DJB provides the tubewell or space for tubewell through which groundwater is drawn by the vendor. This raw water then passes through the RO plant for treatment, after which it is transferred to the water ATMs for dispensing.

The treatment procedure consists of pre-filtration processing, after which water passes through a micro-filtration cartridge. The water is then pumped in through the RO unit filtration using high pressure. The last part of the treatment includes disinfection using ultraviolet rays.

The automated units work as cashless vending machines, where each customer uses a smart card to draw water from it. The DJB has sanctioned RO plants in 29 locations across the city and commissioned a total of 50 water ATMs that have been installed in these areas.

Savda Ghevra, Narela, Holambi Kalan, Batla House, 5/35 Kirti Nagar, Dwarka Sector 3 are some of the locations where these ATMs have been installed. These RO plants and ATMs are being maintained by Piramal Water Pvt Ltd, Tata Power DDL, and Water Health India Pvt Ltd.

When asked about the challenges they’ve faced with installation, a Delhi Jal Board official says, “Most of the target population here demand free water; also, land transfer for the installation of RO plant is difficult.”

Are these a possible solution, then, to the drinking water crisis in the city or a means to decentralise water? He adds, “In the present system, it’s not.”

Several initiatives under way

Nevertheless water ATMs, wherever they are installed, have been making some difference to the lives of users, even if in a piecemeal way.

Sarvajal (meaning “water for all” in Sanskrit) was seeded by Piramal Foundation in 2008. Their 400+ solar-powered cloud-connected water ATMs serve over 5 lakh people daily across the National Capital Territory of Delhi and 15 other Indian states. From manufacturing the ATM machines to supply of water to the maintenance & operation — the entire process is taken care of by Sarvajal.

Water is bought through their ATMs in different areas of Delhi for as low as 25 paise per litre using RFID prepaid smart cards with the cost of water varying slightly according to the location. Earlier, these ATMs dispensed water through coin-based transactions as well, but this was subsequently discontinued after a few instances of vandalism.

The RFID smart cards can be obtained from local vendors stationed at the ATMs. These allow remote/online tracking of each transaction, follow user activity, track when filters need to be changed and also how much water a station has dispensed.

Additionally, during an emergency, bulk texts are sent to users and users can also present queries or complaints using their RFID cards. Employing this technology makes remote monitoring of their distribution network easier and efficient. However, “understanding scarcity of water in different areas is still a challenge”, says Shwetank Gautam of Sarvajal.

In 2015, another such initiative, Pi-lo was started as a test pilot project at the Botanical Garden Metro Station. After six months of successful operations, they got a permit from Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) in 2016; today, they have approximately 56 working ATMs in various metro stations across Delhi.

In 2017, they sought the approval of ASI and installed seven units in different ASI monuments across Delhi as well as ten working units in Uttar Pradesh. Their machines are of two types: Static & Mobile.

Pi-Lo became the first mover of smart water ATMs in Delhi-NCR, and while the cost of a mobile machine ranges from 3 to 3.5 lakh, a static unit costs between 6 to 6.5 lakh. The difference in price is due to an RO plant and chiller unit installed with a static unit, whereas, a mobile machine is used only as a water dispensing unit.

Mobile units have been installed under DMRC, which dispense 250ml of water for Rs 2 and 1 litre of water for Rs 5. The money received from users goes towards maintenance, operations, payments to service operators and for the paper cups provided to users. Static units in ASI monuments and Uttar Pradesh dispense water for free to its users.

Some of these automated water dispensing units have advertisements on them. The money from these ads is spent on maintenance of units and payments to service operators.

On challenges, Deepak, Operations Manager at Pi-lo says, “Nothing major. Only that every new hire of a service engineer or operator takes time to learn the job.” Every unit has an operator to help users, whose timings depend upon the location and season. For example, operators at ASI monuments would be present at the unit from opening to closing hours whereas operators at DMRC locations spend an average of ten hours at the unit. Engineers and senior engineers are allotted a certain number of units to maintain.

In terms of sustainability, these machines are claimed to last for over 10 years. Wastage of RO water in their static units is 10-12% compared to approximately 40% for water treated in regular RO units. Their aim is to make water affordable to all citizens and with minimal wastage.

Users too have responded positively appreciating the clean water and the cups provided for them to drink. Around 7 to 7.5 lakh litres of water have been dispensed so far to 20-21 lakh people through Pi-lo water ATMs, says the company. The supply of water comes from DMRC/ Delhi Jal Board for the static units. Going forward they plan to install 120 more machines.

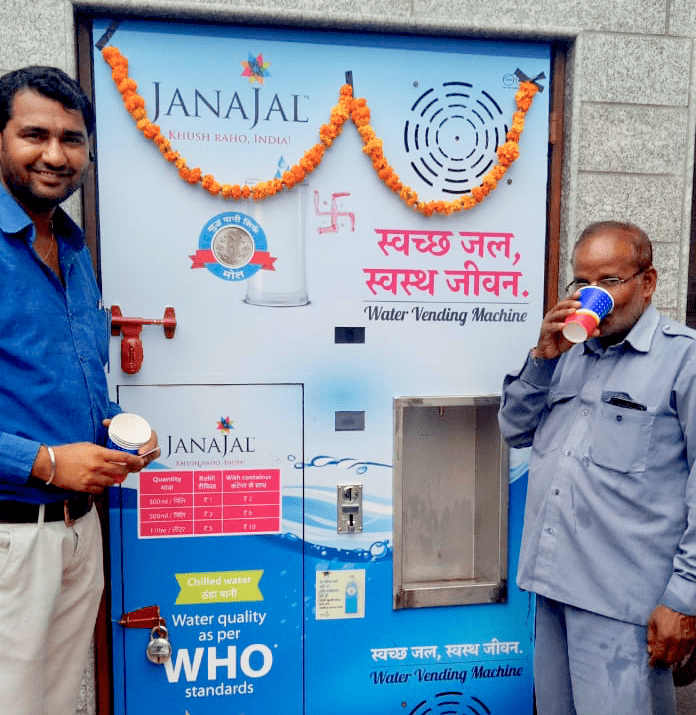

Jana Jal, a social enterprise founded by Parag Agarwal, has installed 28 water ATMs in North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) areas and plans to install 50 more in the next four to five months. Five more have been installed in Ghaziabad Municipal Corporation areas as well.

They also plan to launch ‘Water on Wheels’ (WOW), an initiative which would cover areas close to these ATMs and deliver water on demand through a mobile application. These WOWs are uniquely designed electric vehicles that will be remotely controlled and monitored through a touch screen-based IoT device developed by Jana Jal.

Raw water is provided by NDMC, and all ATMs are installed in a public toilet unit (PTU) which includes facilities like male and female toilets, bank ATMs, water ATMs, wifi set up in Smart City -New Delhi under the NDMC jurisdiction.

“Every drop of water is accounted for not only in terms of consumption, dispensation but also wastage. Waste water generated from the water treatment plant is circulated to toilet units, so that the water is not wasted,” says Praveen Kumar, Joint Managing Director.

Jana Jal’s team maintains all units. Maintenance cost depends on quality of raw water which varies from place to place. “We have not faced any challenges in operations, but we need to publicise these facilities so that more people can regularly use this,” adds Praveen.

Approximately. 1,80,000 litres of drinking water can be dispensed from each machine. One litre can be consumed by four people using a 250ml glass. Thus, one ATM can benefit 1.8 to 5 lakh people per month. In terms of sustainability of the units, each ATM has a life span of 8-10 years. However, certain parts require regular replacement.

When asked if he sees this as a solution to the drinking water crisis in cities and a potential means to decentralise water, Praveen exclaims, “Yes! There is a difference between safe drinking water and piped water. Piped water may be contaminated due to various reasons, but stand alone water ATMs which treat water on the spot and ensure safety of human beings is definitely a solution towards clean drinking water.”

Another company fighting the water battle is Swajal that has installed 30 water ATMs across Delhi at prime locations like CP, LIC Building, Khan Market, and Sarojini Nagar. Their water systems run on solar energy and have cloud-based remote monitoring using their proprietary IoT platform. Water is supplied by the respective municipal bodies. At present, Swajal ATMs are dispensing and purifying 150 million litres of water annually and impacting over 5 lakh lives daily across 15 states in India.

Swajal ATMs have a RFID-based smart card system, but they also have a coin acceptor and mobile wallet compatibility with PayTM, BHIM and other mobile wallets. In urban slums, they partner with local entrepreneurs to increase the accessibility and affordability of clean drinking water which is 75% cheaper than buying bottled water. Based on the sponsor, water is dispensed free or at 30 paise per litre.

What users say

At the Kirti Nagar metro station, a commuter stops by to fill her bottle from the water ATM. Quenching her thirst, she says, “It’s great that I can have chilled clean water for so cheap. This water unit is convenient and affordable.”

At 5/35 Kirti Nagar, residents queue up with their containers to collect drinking water at the ATM whose water supply comes from DJB and is maintained and operated by Tata Power DDL. Naina devi, a resident of the settlement uses her smart card (given to them by Tata) to draw 10 litres of water at the rate of ₹1; recharged every month for Rs 30.

She says, “It’s been four years since this unit was installed. I’m glad I no more have to walk miles to fetch a few litres of water.” Before the units were installed, women and girls from the colony had to trek to other areas (sometimes far away) to collect water as there was absolutely no source of clean water around.

In a colony with approximately 9,000 residents, only around 430 of them have smart cards to access water from the machine, points out Meena, resident and staff appointed by Tata to operate the machine on a daily basis. Although close access to clean water is a relief, another resident of the colony adds, “I wish they supplied more water as 10 litres a day is not sufficient for large families. If they could add another unit in the colony, it’d be very helpful.” Water is dispensed on a daily basis except when the output pipe breaks or supply machine doesn’t work, which, can take a day to a few days to get fixed.

At another water ATM installed opposite the Ministry of Home Affairs in Khan Market, a regular user says, “A cup of clean water (300 ml) for ₹1 is helpful compared to a high-priced bottle of water. The water hasn’t been dispensed for a couple of days now. We’ve complained at a number written on the glass window of the machine.”

Minor glitches notwithstanding, water ATMs bring several benefits. An important point to note is that all the private enterprises mentioned above have created sustainable local jobs and reduced the use of plastic bottles by either providing paper cups or asking users to use their own utensil/ bottle, thereby encouraging a change in behaviour against the use of plastic and creating awareness of its harmful effects.

In India, water-borne diseases affect approximately 38 million people each year, estimates WHO. 780,000 deaths can be attributed to contaminated water and more than 400,000 deaths to diarrhoea. India ranks 120 out of 122 nations for its water quality and 133 out of 180 nations for its water availability. In such circumstances, water ATMs provide a huge opportunity to build healthier and more productive communities.

It’ll be a DREAM-COME TRUE if such ATMs are installed in the South, esp. the water-starved Tamil Nadu and soon enough Karnataka too !! The “Raam Rajya” proclaimed by our Hon’ble Shri HDK shd start thinking of such noble ventures .. to start with at Bengaluru !!