On a busy noon last week, as Kavya, 63, was scouting for medicine for her husband at the Yusuf Sarai market in south Delhi, she noticed that salesmen in many drug stores were either without masks, or were not covering their nose and mouth. The elbowing crowd of customers, too, were not wearing masks.

“I got terribly scared and was virtually in tears,” says a frightened Kavya as she rushed out of the shop. This market is lined with more than 50 drug stores as two big hospitals—AIIMS and the Safdarjung—are in proximity.

At the giant commercial-cum-office complex at Nehru Place, it is business as usual. At an open eatery, groups of office goers can be seen standing together and eating at a table. Street vendors and urchins weave in and out of streaming crowds, several with no masks or masks pulled down on the chin.

“Wearing the mask is a joke… just to avoid chalans,” says Suresh Chopra, managing director of a Hindi news TV channel, a COVID survivor who was hospitalised late November. “Most of the time, people cover just the mouth”.

The same scenario prevails at many other shopping areas and local markets across the capital. “At any given time, 10% of the crowd at the crowded markets do not cover their faces,” says Ram Sagar, an e-rikshawala at Mayur VIhar in east Delhi. “We have no option but to hope for the best and wade through the crowded areas.”

However, there are exceptions. Soon after shops were permitted to function, Atul Puri, owner of Atul Optikos eyewear shop, erected a rope barricade to maintain distance from the counter. He sanitises the eye-examination chamber every time before attending to a new customer. His assistants still wield the infrared thermometer gun and check if the patient is wearing a mask.

“I request women who cover their face with a dupatta and men who use a hankey or towel to change to a mask, which we offer,” says Puri. “If they don’t comply, I refuse to test them. I do the same to those having above-normal temperature.”

Puri feels masks are vanishing from shoppers’ faces as they no longer fear the virus. “Since they have donned it for nearly ten months, a complacent attitude has set in, and now it is chalta hai.”

At a shopping centre in upmarket Safdarjung Enclave, I observe four mask-less youngsters haggling with an auto driver and also another group huddled around tables outside a restaurant. At an adjoining kiosk, the mask is absent from the tea vendor’s face and the server has pulled it down his nose.

The hike in penalty for not wearing the mask has only led to a new trend. Masks have slid down the nose and mouth, and rest on the chin.

For the past two weeks, I have been observing daily at a well-known doctor’s clinic I frequent for pain management in my right shoulder, that patients are not screened before entry and beds, equipment and machines are not sanitised. Just the top sheet is changed, on request. It appears to be the same story at several clinics. “Social distancing, sanitising and wearing masks are increasingly becoming cursory,” said a doctor at the clinic.

Infrared thermometer guns that were earlier ubiquitous at every housing society, office building and complex, grocery, department and other stores, now lie mostly idle.

High Court intervenes

To propel economic activity, Delhi started easing restrictions in markets, and resumed public transport and metro services, leading to large gatherings in public spaces. Observing this, public health experts warned of a sharp rise in coronavirus cases ahead and after the festive season starting October. But the authorities remained unconcerned. They kept saying that the number of new cases was not alarming, patients were recovering and that the death rate was low.

As November dawned, cases began increasing gradually. The capital witnessed a peak on November 10th with 8,600 positive cases. The spike led the government scurrying to arrange more beds in hospitals. Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal blamed the severity of the new wave mainly on air pollution due to stubble burning in neighbouring states. “We had the situation under control until October 20,” said Kejriwal.

The city government’s complacent attitude and inaction drew the wrath of the Delhi High Court, which termed the situation “alarming”. It noted that the quantum of fine for not wearing masks and not maintaining social distancing did not appear to be a deterrent. “Those who are not stepping out of their homes are getting infected because of carelessness of others,” the HC said. The High court also capped the number of attendees at wedding functions at 50, down from 200.

Shaken and stung by the criticism, the Kejriwal government conducted a five-day door-to-door screening of 5.73 million people in ‘high risk areas’ from November 20th after case and death count rose alarmingly. The screening has been extended till December end and will specifically cover senior citizens.

The first preventive measure the Delhi government took was to quadruple the fine to Rs 2,000 for those caught without face shields. And for better enforcement of quarantine measures, some district authorities began setting up micro-containment zones—areas where two or more infections have been reported. These areas which might be as small as a building or even a floor in an apartment complex, are identified and isolated.

As of now, Delhi has 5,669 containment zones (north–166, New Delhi, north west, south west-1377, west, south east, south-833, Shahdara, east, north east and central–in all these 11 districts).

Why the spike in November?

Scientists are yet to reach a consensus on the link between changes in weather and transmission. But numerous studies have found that the causative agent of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, may survive longer in colder climates and hence, the spread. WHO says that cold weather and snow cannot kill the Covid-19 virus.

Health experts, however, blame the nonchalant, Kuchh nahi hota behaviour of Delhi’s citizens for the spiralling numbers. The crowded weekly bazars, the festival season and indifference of authorities responsible for implementing strict control are identified as reasons for the climb in cases.

At a camp in a housing complex in east Delhi, inhabited by journalists, there was hardly anyone around to undergo the Rapid Antigen Detection Test (nasal swab test). “Most citizens are in denial,” said a health official when asked the reasons for this poor turnout. “Secondly, some, on hearing that they have tested positive, skedaddle fearing isolation, stigma and hospitalisation. Many move around freely, visiting markets and public places, and pass on the infection.”

Just ahead of Diwali, authorities recorded a high incidence of infection among traders in markets, especially in old Delhi and west Delhi. These markets had logged heavy footfalls.

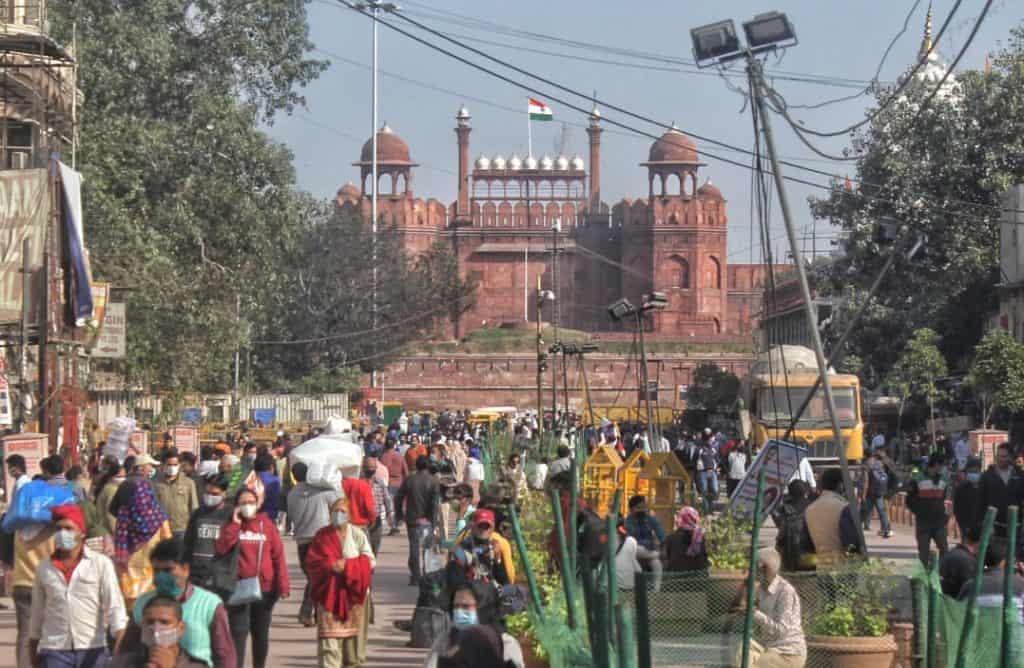

Following Diwali shopping, Delhiites went into a tizzy over the ensuing wedding season. The old Delhi areas — Sadar Bazar, Chandni Chowk and Nai Sarak, known for wholesale business, and Karol Bagh in central Delhi, are milling with crowds. “One has to drive through a wave of humanity to move ahead,” said Pradeep Kumar, an Uber cabby.

Citizens’ own creation

“A person picks up the virus from a new contact and infects his friends and family members, triggering a new wave,” said renowned Chennai-based epidemiologist and a former principal of Christian Medical College, Vellore, Dr Jayaprakash Muliyil. “After remaining in safe confines, when a person moves out, the safety bubble bursts. The spurt is due to people’s change in behaviour as they have become impatient due to socio-economic compulsions,” Dr Muliyil told me. “People themselves are responsible for any new wave.”

Morever, as winter tightens its grip, the city’s homeless will have to be accommodated soon in night shelter homes. This could create another challenge with most states in the north set to experience a harsh winter this year. These homes have been mandated to follow social distancing.

The Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), that runs nearly 300 shelters, will soon add 250 (temporary) tents and porta cabins. These will decongest other shelters and avert the risk of spreading Covid, said an official.

A bigger trial now stares at the government — the army of farmers camped at Delhi’s borders with Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. This could lead to a major spurt in infection, experts fear. The local government is setting up more test centres as social distancing is impossible in this situation. AAP volunteers are trying to ensure that all farmers wear a face shield, but from all the footage aired on footage, that appears to be a far cry.

Taking note of the spread in the country, the Centre, in its fresh guidelines issued on November 30th said markets in containment zones will remain shut until further orders and only those outside containment zones will be allowed to function. Delhi recorded 3,276 fresh coronovirus cases pushing the tally over 5.70 lakh on November 30th. The toll mounted to 9,174.

Muliyil is hopeful that cases in Delhi will drop in a few weeks as is happening in Chennai and Mumbai. “Delhi is fast approaching herd immunity and the pandemic will end on reaching herd immunity. The disease is not dangerous. Efforts should be concentrated on slowing it.”

Which requires Delhiites to wear masks, maintain social distancing, and act responsibly. Something Delhiites are not used to doing.