The mere mention of Cooum conjures up images of a dirty, smelly water body. The pollution of the Cooum river has been an issue that takes centre stage in all discussions around improving life in Chennai. The fate of Chennai’s other water bodies, the Adyar river and Kosasthalaiyar river and the Buckingham canal also mirror that of the Cooum.

Many attempts have been made over the years to clean up Chennai’s polluted rivers. Allocations running into thousands of crores have been made for these projects by various governments, but progress has been slow and incremental.

Read more: Sewage lorries polluting Chennai lakes, drains with impunity

State of rivers in Chennai

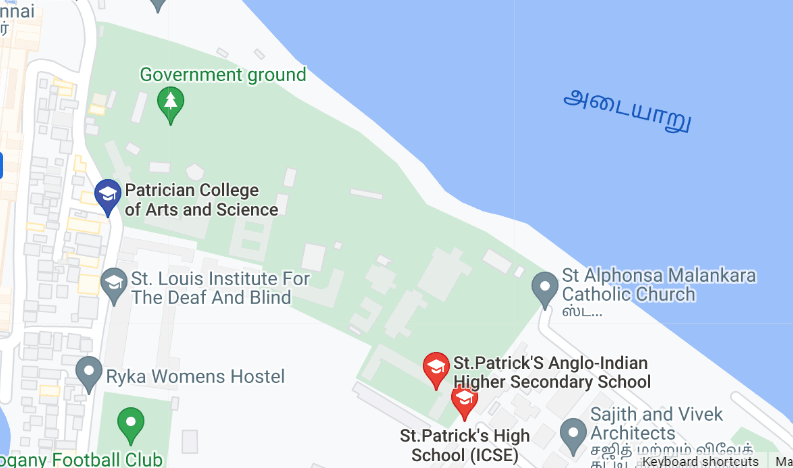

The Central Pollution Control Board has ranked Cooum as the most polluted river in India. The Adyar river also finds a place in the report released in 2022.

The ranking is based on a measure of the Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD).

Biological oxygen demand (BOD) is defined as the amount of dissolved oxygen needed by microorganisms to decompose the organic matter in water. In other words, BOD is the amount of oxygen necessary for organic waste to decompose.

A high level of BOD indicates a low availability of dissolved oxygen needed by the higher organisms, namely the aquatic flora and fauna. Hence, the higher the BOD, the more polluted the water is considered to be.

The Cooum and Adyar rivers have a BOD of 345 mg/l and 40 mg/l respectively.

The acceptable water quality standard for rivers is 3 mg/L BOD for bathing, as per the Central Pollution Control Board rules and the Guidelines for Preparation of Project Reports under National River Conservation Plan and National Ganga River Basin Authority. Water in rivers having a BOD higher than that limit is considered polluted.

By these standards, the current BOD of Cooum is 115 times the level safe for bathing, while that of Adyar is 13.3 times.

In January 2023, the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB) found the Adyar, Cooum and Buckingham Canal to be ‘dead’, as no living species can survive in these rivers at the present levels of pollution. In fact, they found no dissolved oxygen in 23 locations of Adyar and 18 locations of Cooum.

“If you look at the riverbed of Cooum in Egmore, it is black in colour. This leads to the accumulation of toxic gases like hydrogen sulphide and methane, causing a foul odour. These gases will consume the dissolved oxygen in the water, rendering the river unfit for any form of life,” says RJ Ranjit Daniels, an Ecologist and Trustee of Care Earth Trust.

CRRT’s role in river restoration in Chennai

In 2006, the Tamil Nadu Government formed the Adyar Poonga Trust to create an Eco-park known as Tholkappia Poonga spanning 58 acres in Adyar Creek, as part of Phase I of the eco-restoration of the Adyar Creek.

Later, the ambit of the trust expanded to restoring 300 acres of Adyar Creek and Estuary, which became Phase II of the project.

“Phase I of Adyar Creek restoration project definitely improved its conditions. The Adyar Poonga is beautifully made too. Before the restoration, it used to be in a very poor state. However, there was no scientific restoration of the Creek,” says TK Ramkumar, a member of the Monitoring Committee appointed by the Madras High Court to oversee the Poonga restoration.

In 2010, the State Government renamed Adyar Poonga Trust into Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT) with a larger mandate. The objective of CRRT includes the restoration of other waterways of the city, including the rivers of Cooum, Adyar, Kosasthaliyar and Buckingham Canal.

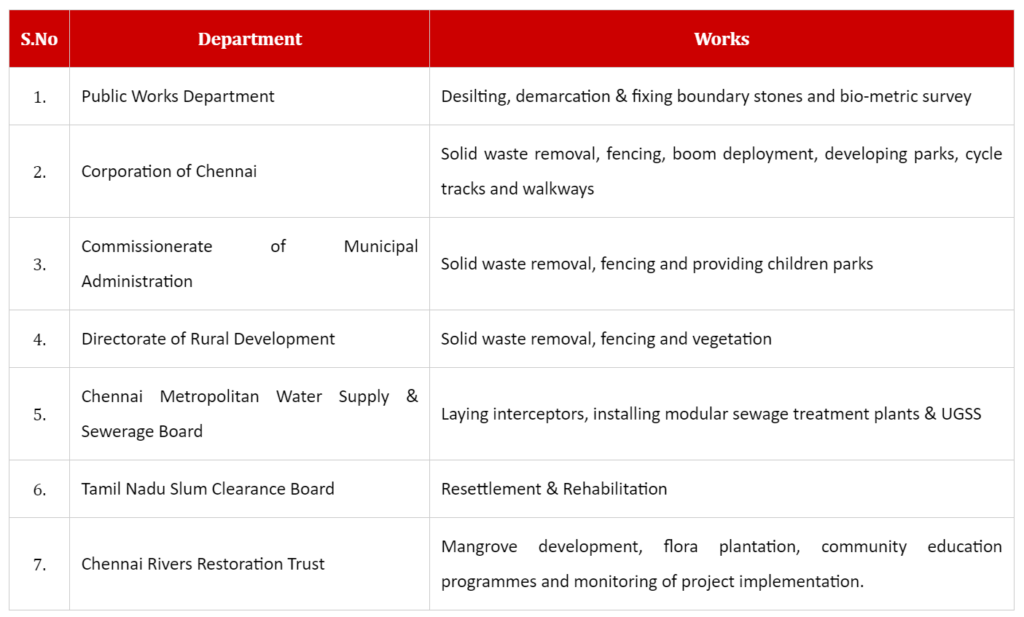

With this goal in mind, CRRT’s eco-restoration plans outline the various steps in reviving Chennai’s rivers. The entire process involves multiple civic and parastatal agencies working in close coordination, with CRRT playing the role of a nodal body.

Steps in eco-restoration of rivers

An official of the CRRT shared the steps followed by the agency for river restoration.

- The boundary of the river is established by the land-owning department. In the case of rivers, it is Water Resources Department (WRD).

- The Resettlement and Rehabilitation (R&R) process begins for settlements and habitats along the rivers. Biometric enumeration of families takes place through the coordinated efforts of the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC), Water Resources Department (WRD) and Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (TNUHB).

- TNUHDB provide tenements for evicted families for resettlement.

- After R&R, WRD widens the river channels and forms the bunds. They also erect flood-protection walls in spots that are vulnerable to flooding.

- WRD also undertakes sustainable river-mouth widening where the rivers join the sea by desilting and clearing the sandbars formed in the mouth of the rivers. This will lead to the tidal exchange of water, which will bring back the life of the river in the upstream areas.

- Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB) is tasked with mitigating the sewage outfalls into the rivers.

- Urban local bodies then take up plantation of native and riverine species along the banks of the rivers to bring back the original life of the river. Apart from that, they are also responsible for solid waste removal, fencing of river boundaries and Riverfront Development.

- As part of Riverfront Development, recreational spaces are developed in areas where spaces are available.

Work undertaken as part of river restoration in Chennai

With the eco-restoration of the Adyar and Cooum in different stages of completion, officials of GCC, CRRT and CMWSSB outline the tasks completed by the respective agencies as part of the project.

| Civic Agency | Work | Adyar | Cooum |

| GCC | Planting native species | Planted from Nandambakkam Bridge to Airport Runway Bridge; Thiru vi ka Bridge to Kotturpuram Bridge | Planted from Napier Bridge to Island Grounds; Thai Moogambigai Dental College and Hospital to Padi Kuppam; among other places. |

| Fencing | Fenced 13.15 km out of 24.67 km (the stretch of the river within GCC limits). | Fenced 18.4 km out of 23.92 km (the stretch of the river within GCC limits). | |

| CMWSSB | Installing sewage pumping stations and treatment plants | Work ongoing on in the canals of MGR, Mambalam, Nandambakkam and Manapakkam. | Sewage treatment plants established in Chetpet and Nungambakkam. |

| Tamil Nadu Water Investment Company | Treating water from stormwater drains before letting it into the rivers | Completed in 14 locations. | Completed in 9 locations. |

| TNUHB | R&R | 4500 families have been relocated and 5000 families remain. | 14,000 families have been relocated and 850 families remain. |

“Near the intertidal zone areas, we plant mangroves across the rivers,” says the GCC official. They have been supplied with a list by CRRT of native species to be planted.

“In the stretches of the rivers with no temporary settlements, GCC has fenced those areas,” says the CRRT official. “In areas with temporary settlements, we have taken up a comprehensive plan for R&R of families within the vulnerable areas within the river course.”

While restoration works are underway for Cooum and Adyar rivers, the restoration of Buckingham Canal has just begun.

“We have started with demarcating the boundaries of Buckingham Canal. Since Buckingham Canal connects both Cooum and Adyar, restoring the canal is bound to have positive effects on the two rivers of Chennai,” says the CRRT official.

The canal will undergo a restoration process similar to the Cooum and Adyar rivers.

Plans have been made to restore 50 km of Kosasthalaiyar with the CRRT in the process of identifying consultants for the preparation of a Detailed Project Report (DPR).

Issues hampering river restoration in Chennai

Experts say that sewage outfalls and solid waste dumping are the two major issues contributing to the pollution of Chennai’s rivers.

Adyar had 67 sewage outfalls and Cooum has 118 as per initial enumeration by the CRRT.

Another issue is the illegal sewage inlets that connect to stormwater drains of the city which finally drain into the rivers.

The lack of adequate sewage infrastructure contributes to the continued pollution of the city’s waterways.

“Let us take areas to the south of Guindy. There are no Sewage Treatment Plants. Residential areas like Tambaram, Mannivakkam and Anakaputhur do not have the infrastructure to treat their sewage. They end up discharging their sewage in Adyar or Palar, ” says Darwin Annadurai, an environmental scientist at Eco Society India.

He also points out that tannery effluents from Chrompet are discharged into the Adyar river in Thiruneermalai. The tannery effluent treatment plant is not functional, he notes.

“Instead of spending crores of money on various activities, CRRT could focus on plugging the sewage outfalls. In a couple of years, the rains will flush out the existing sewage and the rivers will start to revive,” says S Janakarajan, former professor at Madras Institute of Development Studies and President of South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies.

Another issue that environmentalists point to is that the width of the river has become very small due to encroachments which could possibly lead to lesser speed, and therefore stagnancy. This is a huge impediment to river restoration efforts.

A significant part of CRRT’s challenge in restoration also involves resettlement and rehabilitation.

“In certain slum lots, willing beneficiaries face roadblocks in relocating due to facing pushback from some people within the slum,” says the CRRT official. “Commercial parties that have encroached the rivers have gone to the court. Many cases are sub-judice.”

Read more: When eri restoration is just another name for eviction of the working classes

Experts bat for real restoration

“The restoration activities look more like cosmetic interventions than fruitful initiatives,” says Ranjit. “Creating walkways, planting trees and clearing temporary settlements are only giving the rivers a facelift. But they are not really addressing the issue of hydrological restoration.”

Manikandan Prabakaran, a resident of Adyar, highlights the case of the walkway adjacent to the Buckingham Canal near the Kasturbanagar MRTS. “While the walkway has been designed well as a recreational space for adults and kids the stench from Buckingham Canal persists, despite the aesthetic exterior,” he says.

There is also widespread criticism of the resettlement and rehabilitation efforts of the CRRT as part of river restoration.

“They seem to be on a spree to destroy the homes and livelihoods of the economically disadvantaged,” says Darwin, adding that the quality of the rivers has not improved despite the slew of evictions seen by the city.

“Temporary settlements across river banks pollute the rivers very minimally compared to high-income households, industries and commercial spaces. People in slums may not have water supply, let alone taps,” says Ranjit, adding that they are not the primary polluters of Chennai’s rivers.

Ranjit Daniels and TK Ramkumar share some best practices for better restoration:

- Plug sewage outfalls and clear all the solid waste, including debris in the river areas.

- Clean the riverbed.

- Improving the connection of the river mouth to the sea through its expansion will lead to, seawater coming in during high tide, also bringing clean water.

- Acquire lands in Kotturpuram, Nandambakkam and other areas to increase the width and the flow of Adyar. If the river flows at a good speed, there will not be mosquitoes breeding and water hyacinths growing.

- Once the surface area of the river is bigger, oxygenation will happen easily. Also, shallow rivers will support life forms. The natural oxidation of the rivers will revive them.

- Ensure solid waste disposal is handled properly in temporary settlements near the rivers so that the waste is not dumped in the water or the banks.

With more than a decade of functioning with the mandate of cleaning up Chennai’s rivers, the present state of pollution is a damning indictment of the loopholes in the restoration strategy adopted by the CRRT.

Tamilnadu is in very bad state, that we all should be very ashamed of. Every year we have historic flood, people of water rich city killed each other during historic drought, have to rely on desalination plants now, named as most polluted river in the country, etc.. but we have no action plan. Yearly we waste and waste precious rain water or keep making it dirtier. Any extent of the beautification of city will not work unless water and waste management issues are addressed. Its quite pathetic that we do not understand importance of most precious element on earth and we do not understand importance of cleanliness.

Wonderful compilation of facts with timeline..Need more Journalist like Padmaja for a healthier society.

All designs and plans are fine.

Actual implementation is needed to sustain the projects over long years

NbSs are needed to be enforced for getting benefits.

At all 67 outfall Inflows need large medium and small dugouts to contain the sludges and resource the matter.