Meerasa’s story is one of displacement. The son of a boat maker and a resident of Dhonirevu (Karimanal island), one of many villages around the Pulicat lake, Meerasa and his parents were evicted from their home in 1985 during ISRO’s Sriharikota expansion. Meerasa now lives in Jameelabad and has worked in conservation since he graduated from school. But with industrial expansion around Pulicat lake threatening the land and the mangrove forests that surround them, Meerasa fears that history might be repeating itself.

About 50 km north of Chennai, Tamil Nadu, is Pulicat lake, the second largest brackish water ecosystem in India. Known as Pazhaverkadu, meaning “forest of the rooted fruit”, Pulicat lake was once covered by dense mangrove trees. But over the centuries — from mangroves being hacked for the construction of the Dutch fort in the 1600s, to the gradual clearing of forests owing to spreading urbanisation and industrial expansion — the mangroves of Pulicat have now been reduced to sporadic patches along the coast. And the mangrove destruction for industrial expansions have both severely affected biodiversity and endangered the livelihood of the fisherfolk who depend on the mangrove ecosystem.

Read more: These six industries in North Chennai are polluting the air for more than half the year

“Around 1,200 families are completely dependent on the mangroves for their income. They make between 100 to 300 rupees a day during the summer season, and 1,500 to 2000 rupees a day during the monsoon season.” Meerasa says. “Fishing that involves tiger prawns and mud crabs are very lucrative, with a kilo of mud crabs costing as much as 1,500 rupees and tiger prawns costing about 1,200 rupees. Both the tiger prawns and mud crabs need the mangroves to thrive. They provide them with shade as well as feed in the form of falling leaves, and are critical to the livelihood of the fishing communities.” Meerasa says.

The mangroves have many uses, for starters, many marine species use them as nurseries during the early stage of their lives. The mangrove tree shedding, along with the accumulation of bacteria, provides young marine life with plenty of food, as well as a thick refuge to hide from larger animals.

“The Pulicat lagoon ecosystem is highly threatened by natural and anthropogenic factors. Over the years, the mangrove species diversity has significantly reduced, thereby threatening many microniches of a range of fauna that use these habitats as nurseries. Some noteworthy species that breed in mangroves are flathead mullet, the iconic edible oyster Crassostrea madrasensis and Brachyuran crabs.” says Riddhika Ramesh, a scientist at the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History.

According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2007, fisheries lose about 480 kg in annual production for every hectare of forest that is destroyed. The mangroves, while acting as nurseries, preserve the fish stock in the long term, ensuring a reliable source of income for the people who depend on it. Mangroves also provide the community with timber, have enabled ecotourism, and protect the coasts from flooding.

“Many waterlogged muddy areas of mangrove habitat are now transformed to vast arid areas which are dominated by invasive plant species Prosopis juliflora and Casuarina equisetifolia along the fringes of the lagoon. With increasing aridity from reduced rainfall and rise in summer temperature, reduced seawater exchange in the northern part of the lagoon and hypersaline conditions of the lake has made restoration of mangrove species challenging. It is because of this highly complex process that we are losing the biological integrity of a brackish water lagoon system.” Ramesh says.

Yuvan Aves, a naturalist and educator says the wetlands of Pulicat are important because of the mosaic of different ecologies that can be found here. The Kosasthalai, Arani, and Kalangi rivers that empty into this lagoon make it possible for riverine floodplains, tidal flats, salt pans, mangroves, tropical dry evergreen forests, backwaters, coastal sand dunes, sandy beaches and the large Pulicat ecosystem itself to exist.

He goes on to add that the mangroves of Pulicat lake also acts as a natural buffer against floods. “The bioregion is Chennai’s largest flood catchment area and cyclonic buffer zone, for a city that’s constantly frequented by cyclones, it’s important that this land is preserved,” Aves says. “The Kattupalli megaport expansion will also put one-fourth of Chennai’s drinking water that comes from the wellfields and other sources at risk, and would put over 10 lakh people under serious water stress.”

“This is our land and I know that no one else but us will fight for it”

Meerasa remembers when his family was evicted from their village Dhonirevu in May 1985. “Before we were asked to vacate, there was at least a kilometer separating two villages, but once the relocation began, they started stuffing us in the free space between the villages. The overpopulation led to scarcity of water, the overfishing created a strain on the lake, and there were resentment and communal riots between the existing and resettled communities.” Meerasa fears that the expansion plan of the Kattupalli port would have similar consequences. In addition, it threatens around 500 hectares of mangroves, resulting in displacement and loss of livelihood of hundreds of fishing families.

“I became active because this is our land and I know that no one else but us will fight for it,” Meerasa says, talking about his inspiration to protect the mangroves. Driven by a sense of duty to protect the ecosystem that has allowed him and his community their livelihoods, Meerasa started working with CReNIEO (The Center for Research on New International Economic Order), a rural development nonprofit organisation, right after school.

“As far as I can remember, all the efforts to protect the lake have been community-driven. On August 5, 2002, when the Enoor North Thermal power station (North Chennai Thermal Power Station near Ennore Port) released hot water into the lake, fishes, prawns and crabs died by the hundreds. I remember walking into the lake when it was 43.5 degrees Celsius as opposed to the summer high of 35 degrees Celsius. It was the community that protested for five straight days and got the power station to cool the water and change the direction of the flow before sending it back into the river. This motivated me and I’ve been involved in community-driven efforts ever since.”

Read more: Activists write to Home Minister protesting wetland encroachment by public sector units

Meerasa first partnered with CReNIEO in 1988, when he enrolled for a computer course sponsored by the organisation. “There were many outreach programs back then, for example, in the late 1980s, boatmen from Pulicat had to travel all the way to Chennai to get their engines repaired. But then CReNIEO organised a three-month-long engine repair workshop to produce homegrown mechanics, and now all the boat mechanics in Pulicat are a result of that workshop.”

As part of the organisation, Meerasa has been active with community outreach and has worked with over 30 schools these past 20 years. “We organise trips for school students to get familiar with the mangroves, and we’ve also published booklets and teaching material for students and teachers so that they’re informed about their surroundings. It’s important that people develop a feeling of ownership. This is our land, this is our livelihood and our future, and it’s our right to fight for it,” he says.

Fighting off worm poachers

“All of this outreach has paid off because the community takes action and mobilises all on its own today. The boatmen who take tourists to see the mangroves make it a point to never leave anything behind, the villagers get together to clean the lake, and just last month we were approached by women who’d fought off worm poachers. It’s a problem we’ve been having for the past three years, and it’s one that’s caused great harm to the ecosystem,” says Meerasa.

Polychaete worms are found in large quantities on this side of the lake, with one kilo of worms fetching 1,200 rupees and as much as 4,000 rupees when resold in the market. These worms are sought after as feed by prawn farmers and aquarium dealers, who pay agents to acquire them from the lake. But the polychaete worms are important to aquatic life as well as the birds that visit the Pulicat lake.

The main problem arose when hired workers dug two feet holes in the ground to acquire these worms. These holes caused sudden drops in the ground. This resulted in falls and broken bones among the prawn picking women of Pulicat. The women banded together and fought off the poachers. They now pick the worms themselves, but in measured quantities.

Restoring mangroves

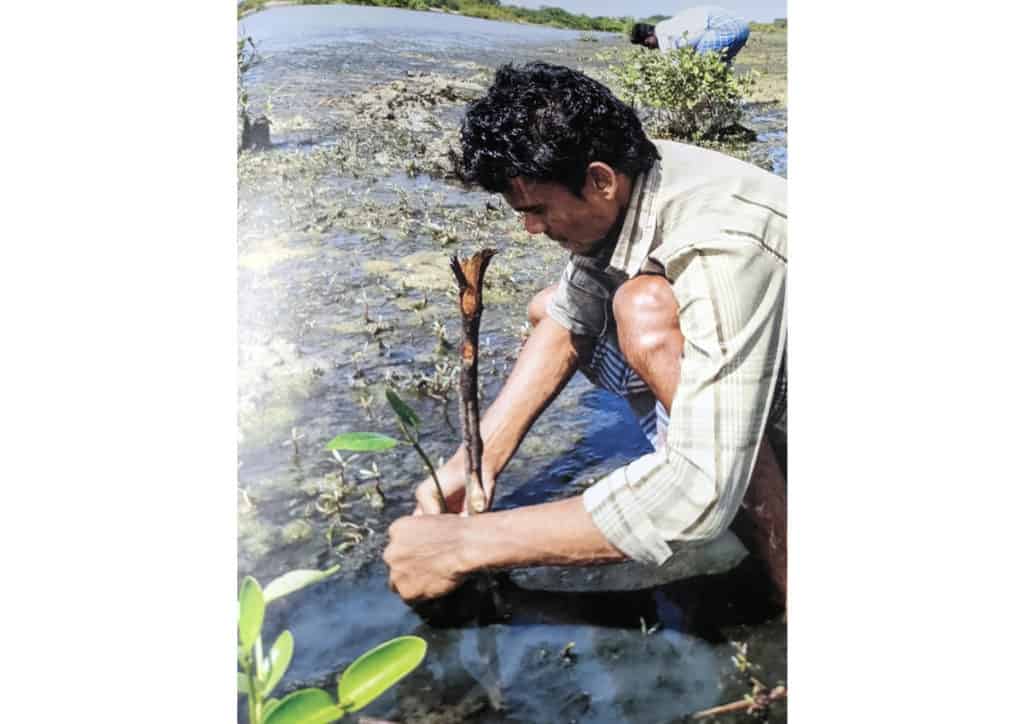

The biggest community-driven undertaking, however, was the mangrove reforestation effort started in 2012. Aided by the Global Nature Fund and partnering with CReNIEO, the project involved fishermen and boatmen, labourers and prawn pickers, and utilised the local community in the restoration process. Thereby empowering them to take charge of their environment and enabling them to regain the livelihoods lost when the mangroves were destroyed.

“In 2012, we began digging canals to improve the water circulation, especially during the summer. We dug around 3000 meters of canals over three years, and began planting the mangroves on the bunds of the canals. We’d tried this out once before in 2010, using the indigenous Avicennia marina seeds, but this was a failure owing to the high mortality rate of the plant. Avicennia marina seeds are about the size of a tamarind and remain small even after growing them in a nursery.”

Meerasa says, “We learned from our mistakes and this time around, we used the Rhizophora mucronata plant. Rhizophora seeds are about a foot long, have lower mortality rates, and grow two to three feet when kept in the nursery. We got the help of the womenfolk around the lake to grow these seeds in nurseries; labourers were paid to work on the canals, and we listed the help of fishermen to plant the mangroves on the bunds.” He adds, “The canals also helped the plants regenerate naturally. Avicennia marina seeds that drifted away would settle on the bunds and grow, and soon a site with 100 plants had over 5,000 plants.

It’s hard to monitor the plants and keep count because they would significantly reduce in numbers during the summer — they would either drift away and the lack of water was a major issue. Just last year we got labourers to manually water the mangroves during the summer.”

But just as everything was going great, tragedy struck. During the monsoon of 2015, Pulicat was hit by a historic flood, a flood that submerged the plants for 10 days and resulted in the loss of about 90% of the restored mangroves. Mangroves have several adaptations that enable them to tolerate up to 100 times more salt than most other plants. They get rid of the salt by storing them in their leaves and bark and shedding them, but at same time they also need freshwater to survive. They would last about a week or so submerged completely by saltwater, after that they begin to deteriorate.

The community lost a lot of its plants during the floods, but haven’t given up yet. The people continued with their reforestation efforts, and are now able to see its advantages materialise.

“I used to find two or three tiger prawns at most, but now after the mangrove growth, I pick 10 to 12 prawns on average,” says Rajee, a prawn picker. Babu, a boatman who helped plant the mangroves, says that he makes detours during his tours of the lake to show tourists the mangroves. “I like to show off these plants, and people are always surprised to learn about a tree that can grow in saltwater,” he says.

Threat of port expansion looms

The Kattupalli megaport, the largest proposed port project in India, is set to be constructed as an expansion to the existing 330-acre L&T shipyard, amidst protests. The public hearing over the construction of the 6111-acre megaport on Kattupalli island was scheduled to take place on January 22 but has been postponed after taking into account the large number of people who would turn up and the potential COVID-19 hazard it could cause.

Despite the looming threat of the Kattupalli port expansion, and the possibility of history repeating itself again, Meerasa is optimistic about the future. He’s convinced that people are better informed this time around, and that they’re more willing to act. “No one knows what the future holds, but we know how to protect our surroundings. We will continue our work preserving our land and our mangroves, and we will continue to fight for our land and our livelihood,” he says.

[This story was first published on Mongabay. It has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here.]

Also read: