Children are often under-prioritized or even disregarded in urban planning and design. It’s estimated that up to 500 children die daily in road crashes around the world; thousands more incur injuries and psychological trauma from collisions with vehicles that can affect them for years.

Whether on the streets or in public spaces, feeling unsafe or uncomfortable in outdoor spaces also discourages children from physical exercise at a time when 80% of children between ages 11-17 are not physically active, and 38 million children under age five are overweight or obese.

The coronavirus pandemic has further highlighted the urgent need for safe outdoor areas for children, many of whom have experienced severe declines in mental and physical health due to restricted access to socialization and activity.

As cities look to COVID-19 recovery as a moment to reevaluate business as usual, we should consider how to better meet the special needs of young people in urban spaces.

But what exactly is a “child-friendly” city? It is more than providing playgrounds. It is a commitment to improving the lives of children by realizing their human rights as articulated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and considering their needs in public policy processes and decisions.

Here are six ways cities can make a difference in the lives of their youngest residents:

1. Lots of green space, accessible to everyone

Neighborhood green spaces can be key to enhancing both mental and physical well-being. Children with ready access to nature and green spaces have reduced levels of stress and aggression, increased ability to concentrate, improved academic performance, and reduced risk of obesity. Urban green spaces can also help improve local air quality.

A child-friendly city protects existing green spaces and resists new development opportunities that compromise them in order to ensure accessible, high-quality green areas and recreational facilities for all residents.

2. Safe walking and cycling infrastructure, especially around schools

Pedestrian and bicycle-oriented spaces support and encourage active mobility for everyone but especially exploration and play by children. In Gurugram, outside Delhi, WRI India found many children were afraid of walking and biking to school, despite a desire to do so, while parents and teachers had high levels of stress about the daily journey to and from school.

Around 60,000 children die from road accidents in India every year, many of them as pedestrians. Across Asia, for every fatality, nearly four children are permanently disabled.

Ensuring safe access for children to strategic locations like schools, parks, schools and community centers is vital. Safe streets not only prevent road injuries and fatalities but allow children to feel comfortable and encourage independent, active travel.

The inaugural WRI Ross Center Prize for Cities was awarded to Amend by an independent jury for its strategic approach to road safety around schools in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Focusing on areas with high crash rates, they were able to reduce injuries and fatalities by significant margins in part through simple infrastructure interventions.

WRI is implementing similar measures in India and elsewhere. In the city of Rohtak, tactical urbanism tools like paints, barricades and chalk have created refuge islands and other safe pedestrian infrastructure. This has helped to reduce crossing distances by 75%, limit turning speeds and reclaim large swaths of road space for pedestrians. These quick, pilot interventions convinced the city to commit to permanent changes.

In a new survey by YouGov for the Child Health Initiative, a global health partnership coordinated by the FIA Foundation, nearly three-quarters of people polled across 11 countries support physical changes to improve children’s road safety during COVID-19. The FIA Foundation has also launched new guidance with UNICEF to help schools, policymakers and local governments enable healthy journeys to school during the pandemic and beyond.

3. Low-speed zones

Keeping vehicle speeds low is crucial for the safety of all pedestrians but especially children. As the speed of a vehicle increases, the driver’s field of vision narrows, making it harder for them to see small children or react to sudden events, like a child running into the street.

In the Tunjuelito District of Bogotá, Colombia, WRI collaborated with the District Mobility Secretariat to implement a 30 kilometer per hour zone in an area known for its high rate of traffic fatalities and injuries. In December 2018, traffic calming measures were also implemented with the help of cones, reflective tape, chalk and paint to improve visibility of the new infrastructure, including around a school zone.

As a result of the twin interventions, driver compliance of posted speed limits went from 29% to 86% overall, and from 36% to 97% in front of the school. In feedback from the community, more than 90% of adults and 86% minors reported feeling safer on their journeys. These results also helped garner both community and city support for scaling up interventions in other neighborhoods.

4. Car-free streets

Some areas may be better off closed to traffic entirely. Temporarily closing streets has proven to be an effective way to increase communal and economic activity by encouraging more foot traffic. It can also create new areas of play for children. Whether it’s Raahgiri Day in India, Ciclovía in Latin America, or Menged Le Sewe in Ethiopia, kids are often among the most excited participants in “open street” days.

Car-free days don’t need to be overly organized or programmed to be successful, they simply need to focus on encouraging physical exercise and play. Street closures can offer relief particularly to dense neighborhoods with few open or green spaces. Prioritizing children in these initiatives will help cities not only provide young people with healthy, safe outdoor spaces, but convey the importance of a clean, sustainable and equitable future.

5. Consider the eye level and cognitive abilities of children

Due to their size, limited cognitive skills and vision, children perceive their surroundings differently than adults. Urban planners should consider the built environment through this perspective, with a focus on public space and mobility.

In a study in Mumbai, WRI India used a “photo-voice method” to gather direct feedback from children on their experience of a school area to better understand how to help them safely experience and navigate their streets.

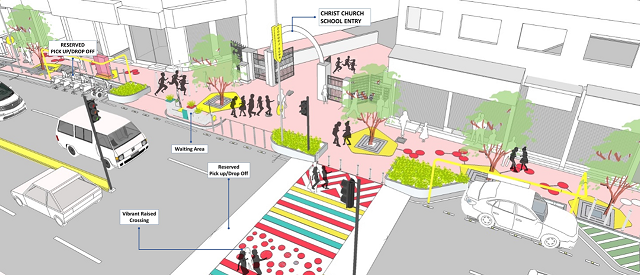

Based on this analysis, WRI developed a set of elements for a safer school zone: vibrant raised crossings designed to control vehicle speeds and be easily visible at children’s eye levels; wide, walkable and barrier-free sidewalks to fit their comfort and coordination levels; tactile guide strips to help children safely follow the sidewalk; warning signage and interactive markings on the sidewalk for play, and dedicated waiting areas at the school’s entrance gates.

6. Clean air zones

Children are particularly vulnerable to air pollution, which can affect neurological development and cause premature death. Due to their height, young children are exposed to 30% more black carbon from vehicle exhaust than adults. The World Health Organization reports almost 1 in 10 deaths from air pollution are children under five years old, and 98% of children under five in low- and middle-income countries are breathing PM2.5 levels above safe levels.

Clean air zones can improve air quality in and around strategic areas like schools and residential communities by discouraging vehicle idling, restricting entry for dirtier vehicles, and encouraging cleaner transport modes and green infrastructure. In the United Kingdom, such policies have successfully inspired action around 40 schools.

Citizen science air quality monitoring projects can also help raise awareness about air quality and increase public engagement – not to mention produce valuable local data. In 2019, the Health and Environment Alliance launched one of the largest citizen-science initiatives to date to measure indoor and outdoor air pollutants at 50 schools across Berlin, London, Paris, Madrid, Sofia and Warsaw.

With active participation from the schools and students, the initiative found that outdoor pollutants from traffic emissions and idling vehicles were influencing the schools’ indoor air quality. Such efforts, which are often low-tech, can be an opportunity to build political support for clean air zones as well as teach children about the science of air quality and get them involved in their communities.

It should go without saying that a child-friendly approach to urban planning does not only benefit children. As Mayor Enrique Peñalosa of Bogotá once said, “Children are a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people.”

As cities and national governments reset after the coronavirus and ponder investments that will hasten a return to economic and social vibrance, incorporating the unique perspectives of children can help create more inclusive, healthier, livable cities. It’s time for cities to start thinking proactively and long-term about how best to serve all residents, including their youngest.

[This post was first published in The City Fix and has been republished with permission. The original can be found here.]