Summer has just started in Chennai. But if present indicators are anything to go by, the summer of 2019 will be an arduous one. As things stand, water currently available for distribution is just over half the city’s basic requirements, and supply in many areas has been cut to just once a week. Making matters worse, ground water levels are at the lowest in three years. So also are storage levels in the four main reservoirs that supply the city.

Groundwater levels in particular are as low as one would expect in April or May. Data collected from 24 wells in Chennai during the first week of January shows an alarming drop in ground water levels — the worst in three years. It only reinforces the fact that the levels may be even worse in February, as the city has not had a spell of rain in the last one month.

A shrinking tale

Eight out of the 24 monitored wells have run dry in the first week of January, according to data from The Rain Centre. These dry wells at Anna Nagar, Parthasarathy temple, Vadapalani, Mylapore Madhava Perumal temple, Ashok Nagar 18th avenue, Nesapakkam, Cancer institute and Adyar Shastri Nagar indicate that the summer ahead may be one of the worst faced by the city, in terms of water availability. Water levels in 16 other wells in arterial corners such as Koyambedu, Saligramam, Chetpet, Kotturpuram, Chamiers Road have fallen by 5 feet (to 11 feet), adding to the ominous picture.

However, according to statistics from the Regional Meteorological Centre (RMC), rainfall in 2016 was even less than in 2018. In 2016, Chennai received 324.6 millimetres (mm) of rainfall and in 2018, the city gathered 390.3 mm. Logically, therefore, groundwater levels in January 2019 should have been better than in January 2017.

During this time last year, Ekaduthangal residents could draw water from their open wells. This year, the water levels have declined by 7 feet, making it tough to even pump water. Pic: Laasya Shekhar

Why do the figures say otherwise, then?

“2015 was a year of excess rainfall, given the flash floods of November-December. This helped in sustaining the groundwater table till early 2017, despite a poor monsoon in 2016. However, the poor Northeast monsoon of 2018 is taking a toll on the city’s ground water level now. Even when it rained, there was a considerable time gap between successive spells, making it tough for groundwater recharge,” said weather blogger Pradeep John, who blogs as Tamil Nadu Weatherman.

However, there are other factors that need attention.

For one thing, it is vital to know the connection between public water supply and groundwater depletion. Residents share that water supply has been scant over the last two months. “ The frequency of water supply has reduced. We get water only once in five to six days, leaving us no choice but to rely on groundwater,” said Uday Kumar, a resident of Vivek Nagar of Pallavaram. Residents of Mambalam complain that they receive water only once in a week. “If this is the case in February, I am scared to think how bad it is going to be in April and May,” says Shwetha V, a resident of Mambalam.

“More and more people are using groundwater to meet their needs, as Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB) has reduced the supply of water, in view of our reservoirs drying up. Treated water from the quarries and desalination plants are quenching the thirst of the city,” said J Saravanan, water resources expert. He was however quick to reassure, adding, “The best part about the city’s water table is the conducive soil that enables easy percolation of water. Aquifers will bounce back, once it rains.”

Unfortunately, weather experts and the India Meteorological Department (IMD) do not predict any productive rains for the next few days, which is only likely to aggravate the current situation.

Reservoirs go dry

The population of Chennai requires 830 MLD (million litres per day) of water. However, the supply has been cut down to 550 MLD now, said a spokesperson of CMWSSB. “We are currently sourcing 200 MLD of water from the two desalination plants, 180 MLD from Veeranam lake, and 170 MLD from the four reservoirs — Poondi, Cholavaram, Chembarambakkam and Red Hills. The department will soon source 30 MLD from the abandoned quarries and 70 MLD from agricultural wells of Tiruvallur and Kancheepuram districts. Krishna water being released from Andhra Pradesh is helpful,” said the spokesperson.

The four lakes/reservoirs reported a combined storage of 893 mcft on 11 February, against 4,969 mcft recorded on the same day last year and 1542 mcft recorded on 11 February 2017, as per Chennai Metro Water records.

| Reservoir | Storage (mcft) on 11 Feb 2017 | Storage (mcft) on 11 Feb 2018 | Storage (mcft) on 11 Feb 2019 |

| Poondi | 797 | 1604 | 157 |

| Cholavaram | 55 | 435 | 48 |

| Red Hills | 414 | 1298 | 648 |

| Chembarambakkam | 276 | 1632 | 40 |

Overlooking the obvious

Chennai is blessed with hundreds of water bodies that can hold the key to recharging ground water. But, these lakes are encroached by various government and private players, seriously affecting the water handling capacity of these water bodies. The current lake levels are 5.5 times lower than last year, and 1.7 times lower than 2017.

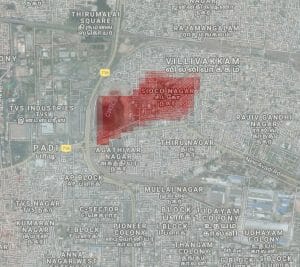

Satellite images released by USGS Landsat Program, a series of Earth-observing satellites co-managed by USGS & NASA show some of the lakes in Chennai that were either encroached or developed between 1977 and 2019 (shown in red) as below:

Lack of a dedicated government authority to maintain lakes within the city limits is seen as the biggest setback. “We don’t have a specific body to manage urban water bodies. The Public Works Department (PWD), which is mainly into surface water irrigation structures, is the custodian of all lakes. But in an urban context, a water body has many roles to play — they are the chief flood and drought mitigators and ground water recharge structures,” points out J Saravanan.

Wanted: More proactive water management, by all

Despite the alarm bells, Chennai Corporation itself has not come up with specific water conservation measures or pointers. The mandate of rainwater harvesting, too, remains largely on paper. The Chennai Metro Water department has been supplying treated sewage water to industries, as a measure to conserve water. However, the department has no eyeballs on whether any wastage exists in the process of distribution and transportation to the city at large.

Rather than frantically opting for external sources such as Krishna water from Andhra, Chennai water authorities should look at strengthening the urban water bodies, say experts. “There are 1400 irrigation tanks in the newly proposed Chennai Metropolitan area of 8800 sq km. There is huge potential to tap water from these tanks by giving them a fresh lease of life,” said S Janakarajan, retired professor, MIDS.

J Saravanan also suggested increasing the storage capacity of the four reservoirs of Chennai, to prevent wastage of water. “During extreme periods of rain, we can a save a lot of water from entering into the sea,” he added. He said that citizens, on the other hand, should opt for measures such as grey water recycling and rain water harvesting.

Some lifestyle changes and easy steps by individuals can also bring about a change in the status of water for the future. The amount of water we waste by not keeping the tap shut while we brush or not turning off the shower while taking a bath is probably much larger than we imagine!

In all, it is going to be a tough few months ahead for the city. It requires concerted action by all to do the best that we can to avoid a serious crisis.