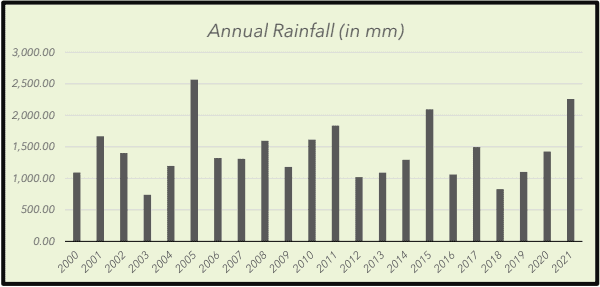

The Chennai floods in 2015 caused damage worth Rs 8481 crore and claimed many lives. In 2021, floods ravaged the city once again, but the effects weren’t quite as bad as 2015. While estimates of the economic damage haven’t been cited; the city was at a standstill. Power had been cut, infrastructure damaged, and the collective sanity of the residents was at a low. These were dark times.

Oddly, only two years before, in 2019, Chennai faced an acute water shortage because of a monsoon that failed to spill any rain. This chain of events illustrates a water paradox arising from irregular monsoons, but it also raises several questions.

Why isn’t water stored from heavy rains and why is it being allowed to run, unused into the sea?

Our ancestors didn’t allow this. They built crescent shaped bunds (or mounds) to trap water so it wouldn’t be wasted. We now call these structures Eris (man-made lakes), and it is central in Tamil culture. Eris still exist, obviously, but the lack of understanding of terrain and hydrology by modern planners and the public has dismantled the system and reduced its efficacy.

Purpose of empty plots

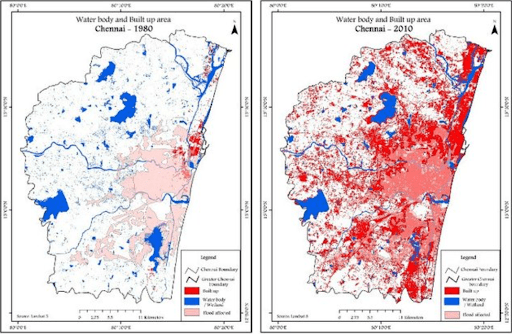

Traditionally, empty land was left in areas adjoining Eris. These areas are flood prone during heavy rains and they were purposely left unconstructed. Now, the desire to develop has taken precedence over the safety of humans. The manner in which planning and development occurs has little regard for nature and this has cost us. We have built residences and IT hubs over hydrological flows and to compound the issue, we cover every inch of soil in impermeable concrete, so where is water to go?

In cities land is a scarce commodity. It’s a crime to leave it (nearly) purposeless. In their current state, empty plots serve a fraction of their potential service and are an eyesore and a burden. They are scattered with garbage and rubble and often overrun by prosopis juliflora – an aggressively growing invasive plant. Still, they are of some service. From experience, empty plots are the first to get flooded and this is a good thing.

Surrounding areas are constantly raised which means water flows and inundates them. They provide a space for the water to go – already acting as a bit of a flood buffer. These plots should remain at a shallower elevation than their surrounds and this is the first thing that should be incentivised.

Read more: Chennai rains: The real reasons why urban floods are a never-ending problem in city

Empowering communities

Land and Eri restoration has been quite common in Chennai and they have been successful in reducing local flooding but (most of) these are tailored to the middle and upper class as opportunities for recreation rather than a mechanism to empower communities.

Without community empowerment, flood prevention will always have to be handled by the state, parastatal bodies and NGOs and never the public. Some form of classism in water restoration efforts will become inevitable and benefits from restoration will be highly local and temporary.

Beyond the services it provides for flood and heat buffering, empty plots can be seen as an opportunity to empower the community by providing livelihoods such as urban agriculture and fisheries.

Incentives to landholders

To kickstart the development of empty plots, incentivisation is required. Carbon credits and tax exemptions are offered commonly to motivate sustainable behaviour. Increasing green spaces, in addition to the benefits it already has, can help Chennai qualify for carbon credits and other grants.

Leasing out land can also tie with a condition for discounted solar energy.

Incentives for land users

Grants will be required during the developmental stages of the empty plots until such time the restoration starts yielding returns but to truly empower and enable the broader community, the land needs to serve livelihoods.

Small transformations to the landscape, for example, the construction of a bund to create a small pond, can serve fishermen who can now rely upon these empty plots for some income. As a bonus, rainwater gets stored, and flooding is reduced.

Like this, several land use cases can be made, not only for flood mitigation but for other urban problems.

For such efforts to succeed, deep understanding of the community is required. Their skillset should be identified and nurtured. There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ plan: the use of empty plots (besides flood reduction) is entirely dependent on the spatial and community context.

Read more: Four recommended steps for a flood-proof Chennai

The way forward

What can be done immediately is to identify a place to pilot the use of such open and empty spaces in the city as a proof of concept. The other steps that can be taken include the identification of flood prone streets and localities that have empty plots.

The biggest challenge in execution would be the work on agreements, incentives and terms for use of the empty land.

Buy in from the local community can be garnered by highlighting the myriad uses empty plots can be put to. From serving as community garden spaces to spaces where food waste can be managed sustainably, empty plots perform useful functions besides aiding in flood-management.

Cutting wells across such plots can also help communities access groundwater and serve as a means to recharge ground water during heavy rainfall.

The value of empty plots has been recognized by community gardeners who have developed vacant lots into areas for urban agriculture and as social spaces, especially in wealthier countries. This has helped develop social capacity while simultaneously providing ecosystem services, including stormwater absorption.

Concepts such as “sponge cities” (cities that use blue and green infrastructure to absorb storm water) have gained popularity after successful implementation in China.

In Chennai, the CMDA recently announced OSR’s will be turned into sponge cities and the conversion of empty plots into sponge lands holds promise.

Use of empty plots across the city, mindful of local context, could prove to be a crucial piece of the urban flooding puzzle that Chennai aims to solve.

(Research for the story was done as part of the Urban Water Bootcamp conducted by Wipro Water Secretariat, a joint initiative of Wipro Foundation and Care Earth Trust.)